Norse settlements in Greenland

Grænlendingar (Icelandic for "Greenlanders") were Norsemen that came from Iceland to settle on the Island of Greenland in the years following 986. The Grænlendingar were the first Europeans to explore and temporarily settle North America. It is assumed that they developed their own language that is referred to as Greenlandic Norse, not to be confused with Eskimo-Aleut Greenlandic language.[1] Their settlements existed for about half a millennium before they were abandoned for reasons still not entirely clear.

The living conditions must have been similar to those in Iceland.[19] Of the 24 children's skeletons at the Thjodhilds Church in Brattahlid, 15 were of infants, one child was three years old, one was seven years old and four were eleven to twelve years old. The infant mortality rate in Iceland in 1850 was of a similar magnitude, even if one takes into account that not all dead newborns were buried at the church. The small number of older children who died indicates good living conditions. Nor do any infectious diseases appear to have raged on a large scale. Of the 53 men outside the common grave, 23 were between 30 and 50 years old. Of the 39 women, there were only three, and only one got older. There are also a few from a group whose age over 20 could not be determined. The average height of men was 171 cm - quite a few were 184–185 cm - and that of women was 156 cm; this is higher than the average in Denmark around 1900. All had good teeth, although significantly worn, and there was no tooth decay. The most common disease found in the skeletons was severe Gout in the back and hips. Some were so crooked and stiff in the joints that they could not be laid down for burial. However, gout was widespread in Scandinavia during the Viking Age. Other diseases can no longer be diagnosed today. The custom of the burial place was also adopted from Norway and Iceland: female skeletons predominate in the north and male skeletons in the south of the church. The greater the distance from the church, the more superficial the burial, which suggests that the distance of the grave from the church depended on the social status of the dead person.

The Greenlandic economy was based primarily on three pillars: livestock farming, hunting and catching animals, which provided food, and trade goods in varying proportions.[20] Because of the large pasture areas required for livestock breeding, the farms were widely separated from each other and were effectively self-sufficient.

The Norwegian textbook Konungs skuggsjá (King's Mirror) reports in the 13th century that the Greenlandic farmers lived primarily on meat, milk (Skyr, a sour milk product similar to our quark), butter and cheese. Archaeologist Thomas McGovern from the City University of New York used rubbish piles to study the diet of Scandinavian Greenlanders. He found that the meat diet consisted on average of 20 percent beef, 20 percent goat and sheep meat, 45 percent seal meat, 10 percent caribou and 5 percent other meat, with the proportion of caribou and seal meat being significantly higher in the poorer western settlement was than in the eastern settlement.[21] Apparently the inhabitants also regularly fished; because floats and weights from fishing nets were found in the settlements.

Finds of hand mills in some farms in the eastern settlement suggest that grain was also grown to a small extent in favored locations. But it was probably mainly imported. The Konungs skuggsjá reports that only the most powerful Bonden (with farms in the best locations) grew some grain for their own use. Most residents don't even know what bread is and have never seen one.

An important source of vitamins was "Kvan" (Angelica), which was brought to Greenland by the settlers and can still be found in gardens there today. Stems and roots can be prepared as a salad or vegetable.

The constant lack of wood proved to be a problem. At the turn of the millennium, only small Dwarf Birchs and Dwarf Willows grew in Greenland, and their use as timber was limited. The driftwood washed ashore with the Gulf Stream was of inferior quality. Therefore, lumber was an important (and expensive) imported commodity.

Other crucial imports were iron implements and weapons. There were no known ore deposits in Greenland at the time of the Vikings. The already not very productive smelting of iron ore quickly reached its limits due to the lack of suitable fuel (charcoal), so that the settlements were almost entirely dependent on imports. An example shows how dramatic the iron shortage was: During excavations in the Western Settlement in the 1930s, a battle ax was found. It was modeled down to the smallest detail on an iron ax, but made from whale bone.[22]

Besides drying, curing was the only way to preserve meat. This required salt, which also had to be imported.

The settlement also had a number of export goods that were very popular in the rest of Europe:

The white Gyrfalcons of Greenland were a very sought-after export item and reached the Arab countries along complex trade routes. The narwhal tusk, which was believed in European royal and princely courts to be able to neutralize poison, was even more highly prized. It was assumed that the snail-like, twisted and pointed horn came from the legendary unicorn.

Both individual farmers and groups of farmers organised summer trips to the more northerly Disko Bay area, where they hunted walruses, narwhals and polar bears for their skins, hides and ivory. Besides their use in making garments and shoes, these resources also functioned as a form of currency, as well as providing the most important export commodities.[20] Strong and durable ship ropes were made from walrus skins.

The Greenland settlements carried on a trade with Europe in ivory from walrus tusks, as well as exporting rope, sheep, seals, wool and cattle hides (according to one 13th-century account).[23]

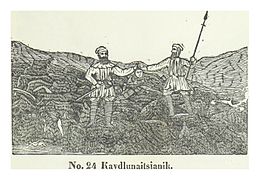

Both archaeological finds and written evidence show that there were encounters between the Eskimo cultures and Scandinavians. Whether these encounters were regular trade relations or just occasional - possibly warlike - contacts is controversial. Oral traditions of the Inuit, which were only recorded in writing in the 18th and 19th centuries, report several military conflicts. Scandinavian relics, especially iron objects, have been discovered several times in Inuit archaeological sites. It is unknown whether these were obtained through peaceful exchange or robbery.

The Saga of Erik the Red (Eiríks saga rauða) tells of a battle that the Icelander Thorfinn Karlsefni fought with the Skrælingar and in which two of Karlsefni's men and four Inuit were killed. In the Icelandic Gottskálks Annálar it is recorded for 1379 that Skrælingar raided the Grænlendingar, killed 18 men and enslaved two servants. However, the authenticity and accuracy of this source is doubted by some historians,[24] and both Jared Diamond and Jens Melgaard caution that it may actually describe an attack that occurred between Norse and Sami people in Northern Europe, or an attack on the Icelandic coast by European pirates, assuming such an attack really did occur.[25] A church document describes a 1418 attack that has been attributed to Inuit people by modern scholars, however Historian Jack Forbes has said that this supposed attack actually refers to a Russian-Karelian attack on Norse settlers in northern Norway, which was known locally as "Greenland" and has been mistaken by modern scholars for the American Greenland. Archeological evidence has failed to find any violence by the Inuit people against Norse settlers.[26]

Bibliography

Secondary literature