Operation Downfall

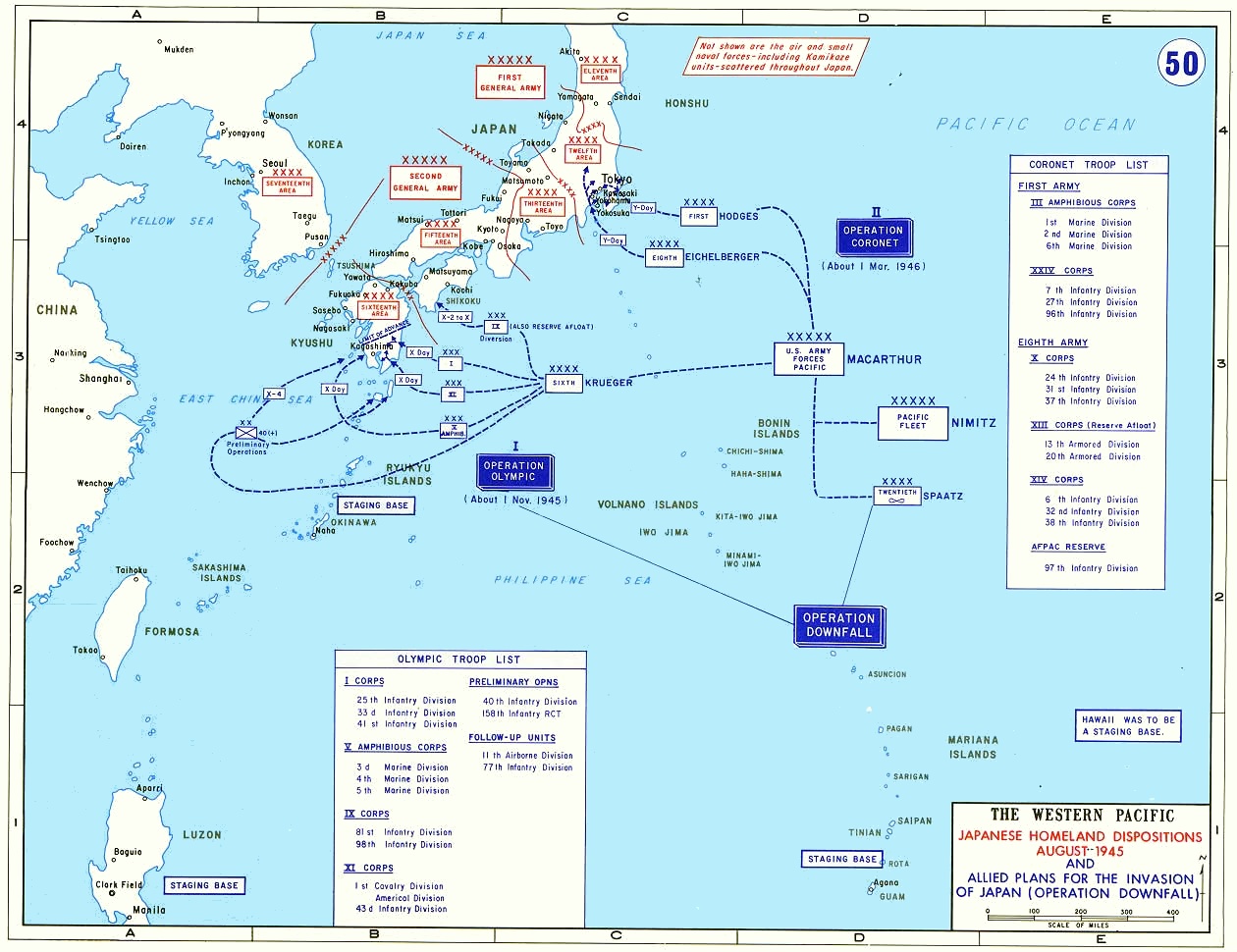

Operation Downfall was the proposed Allied plan for the invasion of the Japanese home islands near the end of World War II. The planned operation was canceled when Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Soviet declaration of war, and the invasion of Manchuria.[1] The operation had two parts: Operation Olympic and Operation Coronet. Set to begin in November 1945, Operation Olympic was intended to capture the southern third of the southernmost main Japanese island, Kyūshū, with the recently captured island of Okinawa to be used as a staging area. In early 1946 would come Operation Coronet, the planned invasion of the Kantō Plain, near Tokyo, on the main Japanese island of Honshu. Airbases on Kyūshū captured in Operation Olympic would allow land-based air support for Operation Coronet. If Downfall had taken place, it would have been the largest amphibious operation in history, surpassing D-Day.[2]

"Invasion of Japan" redirects here. For the failed Mongol invasion attempts, see Mongol invasions of Japan.Operation Downfall

Before August 1945

Defeat the Empire of Japan

See Orders of battle

Cancelled after the unconditional surrender of Japan on 15 August 1945

Japan's geography made this invasion plan obvious to the Japanese as well; they were able to accurately predict the Allied invasion plans and thus adjust their defensive plan, Operation Ketsugō (ja), accordingly. The Japanese planned an all-out defense of Kyūshū, with little left in reserve for any subsequent defense operations. Casualty predictions varied widely, but were extremely high. Depending on the degree to which Japanese civilians would have resisted the invasion, estimates ran up into the millions for Allied casualties.[3]

Allied re-evaluation of Operation Olympic[edit]

Air threat[edit]

US military intelligence initially estimated the number of Japanese aircraft to be around 2,500.[55] The Okinawa experience was bad for the US—almost two fatalities and a similar number wounded per sortie—and Kyūshū was likely to be worse. To attack the ships off Okinawa, Japanese planes had to fly long distances over open water; to attack the ships off Kyūshū, they could fly overland and then short distances out to the landing fleets. Gradually, intelligence learned that the Japanese were devoting all their aircraft to the kamikaze mission and taking effective measures to conserve them until the battle. An Army estimate in May was 3,391 planes; in June, 4,862; in August, 5,911. A July Navy estimate, abandoning any distinction between training and combat aircraft, was 8,750; in August, 10,290.[56] By the time the war ended, the Japanese actually possessed some 12,700 aircraft in the Home Islands, roughly half kamikazes.[57] Ketsu plans for Kyushu envisioned committing nearly 9,000 aircraft according to the following sequence:[58]