Optical illusion

In visual perception, an optical illusion (also called a visual illusion[2]) is an illusion caused by the visual system and characterized by a visual percept that arguably appears to differ from reality. Illusions come in a wide variety; their categorization is difficult because the underlying cause is often not clear[3] but a classification[1][4] proposed by Richard Gregory is useful as an orientation. According to that, there are three main classes: physical, physiological, and cognitive illusions, and in each class there are four kinds: Ambiguities, distortions, paradoxes, and fictions.[4] A classical example for a physical distortion would be the apparent bending of a stick half immerged in water; an example for a physiological paradox is the motion aftereffect (where, despite movement, position remains unchanged).[4] An example for a physiological fiction is an afterimage.[4] Three typical cognitive distortions are the Ponzo, Poggendorff, and Müller-Lyer illusion.[4] Physical illusions are caused by the physical environment, e.g. by the optical properties of water.[4] Physiological illusions arise in the eye or the visual pathway, e.g. from the effects of excessive stimulation of a specific receptor type.[4] Cognitive visual illusions are the result of unconscious inferences and are perhaps those most widely known.[4]

This article is about visual perception. For the album, see Optical Illusion (album). For the film, see Optical Illusions (film).

Pathological visual illusions arise from pathological changes in the physiological visual perception mechanisms causing the aforementioned types of illusions; they are discussed e.g. under visual hallucinations.

Optical illusions, as well as multi-sensory illusions involving visual perception, can also be used in the monitoring and rehabilitation of some psychological disorders, including phantom limb syndrome[5] and schizophrenia.[6]

Physical visual illusions[edit]

A familiar phenomenon and example for a physical visual illusion is when mountains appear to be much nearer in clear weather with low humidity (Foehn) than they are. This is because haze is a cue for depth perception,[7] signalling the distance of far-away objects (Aerial perspective).

The classical example of a physical illusion is when a stick that is half immersed in water appears bent. This phenomenon was discussed by Ptolemy (c. 150)[8] and was often a prototypical example for an illusion.

Physiological visual illusions[edit]

Physiological illusions, such as the afterimages[9] following bright lights, or adapting stimuli of excessively longer alternating patterns (contingent perceptual aftereffect), are presumed to be the effects on the eyes or brain of excessive stimulation or interaction with contextual or competing stimuli of a specific type—brightness, color, position, tile, size, movement, etc. The theory is that a stimulus follows its individual dedicated neural path in the early stages of visual processing and that intense or repetitive activity in that or interaction with active adjoining channels causes a physiological imbalance that alters perception.

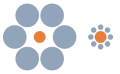

The Hermann grid illusion and Mach bands are two illusions that are often explained using a biological approach. Lateral inhibition, where in receptive fields of the retina receptor signals from light and dark areas compete with one another, has been used to explain why we see bands of increased brightness at the edge of a color difference when viewing Mach bands. Once a receptor is active, it inhibits adjacent receptors. This inhibition creates contrast, highlighting edges. In the Hermann grid illusion, the gray spots that appear at the intersections at peripheral locations are often explained to occur because of lateral inhibition by the surround in larger receptive fields.[10] However, lateral inhibition as an explanation of the Hermann grid illusion has been disproved.[11]

[12]

[13]

[14]

[15]

More recent empirical approaches to optical illusions have had some success in explaining optical phenomena with which theories based on lateral inhibition have struggled.[16]

Cognitive illusions are assumed to arise by interaction with assumptions about the world, leading to "unconscious inferences", an idea first suggested in the 19th century by the German physicist and physician Hermann Helmholtz.[17] Cognitive illusions are commonly divided into ambiguous illusions, distorting illusions, paradox illusions, or fiction illusions.

Pathological visual illusions (distortions)[edit]

A pathological visual illusion is a distortion of a real external stimulus[32] and is often diffuse and persistent. Pathological visual illusions usually occur throughout the visual field, suggesting global excitability or sensitivity alterations.[33] Alternatively visual hallucination is the perception of an external visual stimulus where none exists.[32] Visual hallucinations are often from focal dysfunction and are usually transient.

Types of visual illusions include oscillopsia, halos around objects, illusory palinopsia (visual trailing, light streaking, prolonged indistinct afterimages), akinetopsia, visual snow, micropsia, macropsia, teleopsia, pelopsia, metamorphopsia, dyschromatopsia, intense glare, blue field entoptic phenomenon, and purkinje trees.

These symptoms may indicate an underlying disease state and necessitate seeing a medical practitioner. Etiologies associated with pathological visual illusions include multiple types of ocular disease, migraines, hallucinogen persisting perception disorder, head trauma, and prescription drugs. If a medical work-up does not reveal a cause of the pathological visual illusions, the idiopathic visual disturbances could be analogous to the altered excitability state seen in visual aura with no migraine headache. If the visual illusions are diffuse and persistent, they often affect the patient's quality of life. These symptoms are often refractory to treatment and may be caused by any of the aforementioned etiologies, but are often idiopathic. There is no standard treatment for these visual disturbances.

![Watercolor illusion: this shape's yellow and blue border create the illusion of the object being pale yellow rather than white[42]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/20/Subjectively_constructed_water-color.svg/120px-Subjectively_constructed_water-color.svg.png)

![Subjective cyan filter, left: subjectively constructed cyan square filter above blue circles, right: small cyan circles inhibit filter construction[43][44]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/ca/Optical_illusion_-_subjectively_constructed_cyan_sqare_filter_above_blue_cirles.gif/120px-Optical_illusion_-_subjectively_constructed_cyan_sqare_filter_above_blue_cirles.gif)

![Pinna's illusory intertwining effect[45] and Pinna illusion (scholarpedia).[46] The picture shows squares spiralling in, although they are arranged in concentric circles.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/45/Pinna%27s_illusory_intertwining_effect.gif/120px-Pinna%27s_illusory_intertwining_effect.gif)

![Pinna-Brelstaff illusion: the two circles seem to move when the viewer's head is moving forwards and backwards while looking at the black dot.[47]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b1/Revolving_circles.svg/120px-Revolving_circles.svg.png)