Ovarian vein syndrome

Ovarian vein syndrome is a rare (possibly not uncommon, certainly under-diagnosed) condition in which a dilated ovarian vein compresses the ureter (the tube that brings the urine from the kidney to the bladder). This causes chronic or colicky abdominal pain, back pain and/or pelvic pain. The pain can worsen on lying down or between ovulation and menstruation.[2][3] There can also be an increased tendency towards urinary tract infection or pyelonephritis (kidney infection). The right ovarian vein is most commonly involved, although the disease can be left-sided or affect both sides. It is currently classified as a form of pelvic congestion syndrome.

Mechanism[edit]

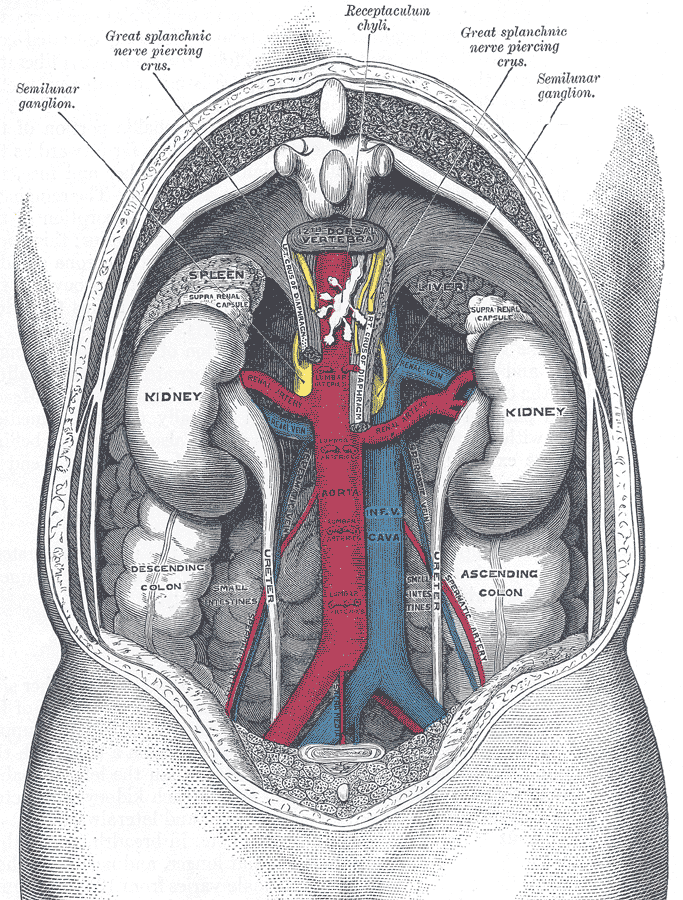

Normally, the ovarian vein crosses over the ureter at the level of the fourth or fifth lumbar vertebra. The ureter itself courses over the external iliac artery and vein.[4] Thus, these vessels can impinge on the ureter causing obstruction. The left ovarian vein ends in the left renal vein whereas the right ovarian vein normally enters into the inferior vena cava.[1] In the case of right ovarian vein syndrome, the vein often ends in the renal vein. This is thought to contribute to venous engorgement, in analogy to what is seen in varicoceles, which arise more commonly on the left side. The straight angle between the ovarian vein (or testicular vein in males in the case of varicocoele) and the renal vein has been proposed as a cause of decreased blood return.

A related diagnosis is nutcracker syndrome where the left renal vein is described as being compressed between the aorta and the superior mesenteric artery. This is reported to cause collateral flow paths to open up to drain the left kidney i.e. reversed flow (reflux caudally) in the left renal vein. Pelvic Congestion Syndrome, vaginal and vulval varices, lower limb varices are clinical sequelae. Virtually all such patient are female and have been pregnant, often multiply.

The ovarian vein often displays incompetent valves. This has been observed more often in women with a higher number of previous pregnancies. Pressure from the baby might hinder the return of blood through the ovarian vein. However, dilation of the urinary tract is a normal observation in pregnancy, due to mechanical compression and the hormonal action of progesterone. Ovarian vein dilatation might also follow venous thrombosis (clotting inside the vein).

Another proposed mechanism of obstruction is when the ovarian vein and ureter both run through a sheath of fibrous tissue, following a local inflammation. This could be seen as a localised form of retroperitoneal fibrosis.[4]

Following obstruction, the ureter displays an abnormal peristalsis (contractions) towards the kidney instead of towards the bladder. This is thought to cause the colicky pain (similar to renal colic), and it is relieved after surgical decompression.

Diagnosis[edit]

Since it is a rare disease, it remains a diagnosis of exclusion of other conditions with similar symptoms. The diagnosis is supported by the results of imaging studies such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasound of the abdomen (with or without doppler imaging) or intravenous urography.

Specialist vascular ultrasonographers should routinely look for left ovarian vein reflux in patients with lower limb varices especially if not associated with long or short saphenous reflux. The clinical pattern of varices differs between the two types of lower limb varices.

CT scanning is used to exclude abdominal or pelvic pathology. CT-Angiography/Venography can often demonstrate left ovarian vein reflux and image an enlarged left ovarian vein but is less sensitive and much more expensive than duplex Doppler ultrasound examination. Ultrasound requires that the ultrasonographer be experienced in venous vascular ultrasound and so is not always readily available. A second specialist ultrasound exam remains preferable to a CT scan.

As a wide range of pelvic and abdominal pathology can cause symptoms consistent with those symptoms due to left ovarian vein reflux, prior to embolisation of the left ovarian vein, a careful search for such diagnoses is essential. Consultation with general surgeons, gynaecologists, and possibly CT scanning should always be considered.

Treatment[edit]

Treatment consists of painkillers and surgical ablation of the dilated vein. This can be accomplished with open abdominal surgery (laparotomy) or keyhole surgery (laparoscopy).[5] Recently, the first robot-assisted surgery was described.[6]

Another approach to treatment involves catheter-based embolisation,[7] often preceded by phlebography to visualise the vein on X-ray fluoroscopy.[3][8]

Ovarian vein coil embolisation is an effective and safe treatment for pelvic congestion syndrome and lower limb varices of pelvic origin. Many patients with lower limb varices of pelvic origin respond to local treatment i.e. ultrasound guided sclerotherapy. In those cases, ovarian vein coil embolisation should be considered second line treatment to be used if veins recur in a short time period i.e. 1–3 years. This approach allows further pregnancies to proceed if desired. Bilateral coil embolisation is not advised if a future pregnancy is possible. This treatment has largely superseded operative options.Coil embolisation requires exclusion of other pelvic pathology, expertise in endovascular surgery, correct placement of appropriate sized coils in the pelvis and also in the upper left ovarian vein, careful pre- and post-procedure specialist vascular ultrasound imaging, a full discussion of the procedure with the patient i.e. informed consent. Complications, such as coil migration, are rare but reported. Their sequelae are usually minor.

If a Nutcracker compression (see below) is discovered, operative relocation of the renal vein should be considered before embolization of the ovarian vein. Stenting is not advised. Reducing outflow obstruction should always be the main objective.