Photoreceptor cell

A photoreceptor cell is a specialized type of neuroepithelial cell found in the retina that is capable of visual phototransduction. The great biological importance of photoreceptors is that they convert light (visible electromagnetic radiation) into signals that can stimulate biological processes. To be more specific, photoreceptor proteins in the cell absorb photons, triggering a change in the cell's membrane potential.

This article is about cellular photoreceptors. For other types of photoreceptors, see Photoreceptor (disambiguation).Photoreceptor cell

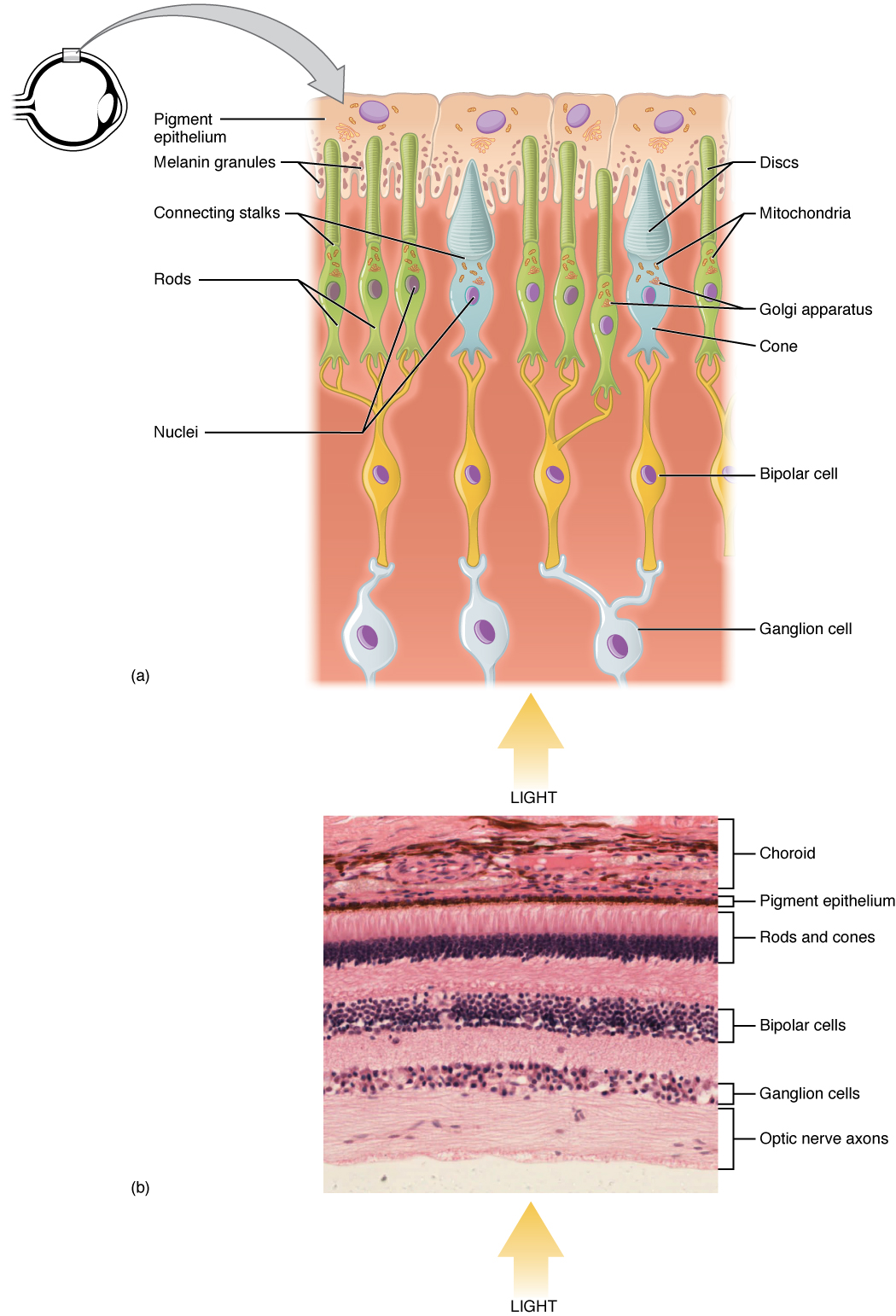

There are currently three known types of photoreceptor cells in mammalian eyes: rods, cones, and intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. The two classic photoreceptor cells are rods and cones, each contributing information used by the visual system to form an image of the environment, sight. Rods primarily mediate scotopic vision (dim conditions) whereas cones primarily mediate photopic vision (bright conditions), but the processes in each that supports phototransduction is similar.[1] The intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells were discovered during the 1990s.[2] These cells are thought not to contribute to sight directly, but have a role in the entrainment of the circadian rhythm and the pupillary reflex.

Development[edit]

The key events mediating rod versus S cone versus M cone differentiation are induced by several transcription factors, including RORbeta, OTX2, NRL, CRX, NR2E3 and TRbeta2. The S cone fate represents the default photoreceptor program; however, differential transcriptional activity can bring about rod or M cone generation. L cones are present in primates, however there is not much known for their developmental program due to use of rodents in research. There are five steps to developing photoreceptors: proliferation of multi-potent retinal progenitor cells (RPCs); restriction of competence of RPCs; cell fate specification; photoreceptor gene expression; and lastly axonal growth, synapse formation and outer segment growth.

Early Notch signaling maintains progenitor cycling. Photoreceptor precursors come about through inhibition of Notch signaling and increased activity of various factors including achaete-scute homologue 1. OTX2 activity commits cells to the photoreceptor fate. CRX further defines the photoreceptor specific panel of genes being expressed. NRL expression leads to the rod fate. NR2E3 further restricts cells to the rod fate by repressing cone genes. RORbeta is needed for both rod and cone development. TRbeta2 mediates the M cone fate. If any of the previously mentioned factors' functions are ablated, the default photoreceptor is a S cone. These events take place at different time periods for different species and include a complex pattern of activities that bring about a spectrum of phenotypes. If these regulatory networks are disrupted, retinitis pigmentosa, macular degeneration or other visual deficits may result.[12]

Non-human photoreceptors[edit]

Rod and cone photoreceptors are common to almost all vertebrates. The pineal and parapineal glands are photoreceptive in non-mammalian vertebrates, but not in mammals. Birds have photoactive cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-contacting neurons within the paraventricular organ that respond to light in the absence of input from the eyes or neurotransmitters.[17] Invertebrate photoreceptors in organisms such as insects and molluscs are different in both their morphological organization and their underlying biochemical pathways. This article describes human photoreceptors.