Plague (disease)

Plague is an infectious disease caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis.[2] Symptoms include fever, weakness and headache.[1] Usually this begins one to seven days after exposure.[2] There are three forms of plague, each affecting a different part of the body and causing associated symptoms. Pneumonic plague infects the lungs, causing shortness of breath, coughing and chest pain; bubonic plague affects the lymph nodes, making them swell; and septicemic plague infects the blood and can cause tissues to turn black and die.[2][1]

This article is about the disease caused by Yersinia pestis. For other uses, see Plague.Plague

1–7 days after exposure[2]

Gentamicin and a fluoroquinolone[3]

≈10% risk of death (with treatment)[4]

≈600 cases a year[2]

The bubonic and septicemic forms are generally spread by flea bites or handling an infected animal,[1] whereas pneumonic plague is generally spread between people through the air via infectious droplets.[1] Diagnosis is typically by finding the bacterium in fluid from a lymph node, blood or sputum.[2]

Those at high risk may be vaccinated.[2] Those exposed to a case of pneumonic plague may be treated with preventive medication.[2] If infected, treatment is with antibiotics and supportive care.[2] Typically antibiotics include a combination of gentamicin and a fluoroquinolone.[3] The risk of death with treatment is about 10% while without it is about 70%.[4]

Globally, about 600 cases are reported a year.[2] In 2017, the countries with the most cases include the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar and Peru.[2] In the United States, infections occasionally occur in rural areas, where the bacteria are believed to circulate among rodents.[5] It has historically occurred in large outbreaks, with the best known being the Black Death in the 14th century, which resulted in more than 50 million deaths in Europe.[2]

Transmission of Y. pestis to an uninfected individual is possible by any of the following means:[18]

Yersinia pestis circulates in animal reservoirs, particularly in rodents, in the natural foci of infection found on all continents except Australia. The natural foci of plague are situated in a broad belt in the tropical and sub-tropical latitudes and the warmer parts of the temperate latitudes around the globe, between the parallels 55° N and 40° S.[18]

Contrary to popular belief, rats did not directly start the spread of the bubonic plague. It is mainly a disease in the fleas (Xenopsylla cheopis) that infested the rats, making the rats themselves the first victims of the plague. Rodent-borne infection in a human occurs when a person is bitten by a flea that has been infected by biting a rodent that itself has been infected by the bite of a flea carrying the disease. The bacteria multiply inside the flea, sticking together to form a plug that blocks its stomach and causes it to starve. The flea then bites a host and continues to feed, even though it cannot quell its hunger, and consequently, the flea vomits blood tainted with the bacteria back into the bite wound. The bubonic plague bacterium then infects a new person and the flea eventually dies from starvation. Serious outbreaks of plague are usually started by other disease outbreaks in rodents or a rise in the rodent population.[19]

A 21st-century study of a 1665 outbreak of plague in the village of Eyam in England's Derbyshire Dales – which isolated itself during the outbreak, facilitating modern study – found that three-quarters of cases are likely to have been due to human-to-human transmission, especially within families, a much bigger proportion than previously thought.[20]

Diagnosis[edit]

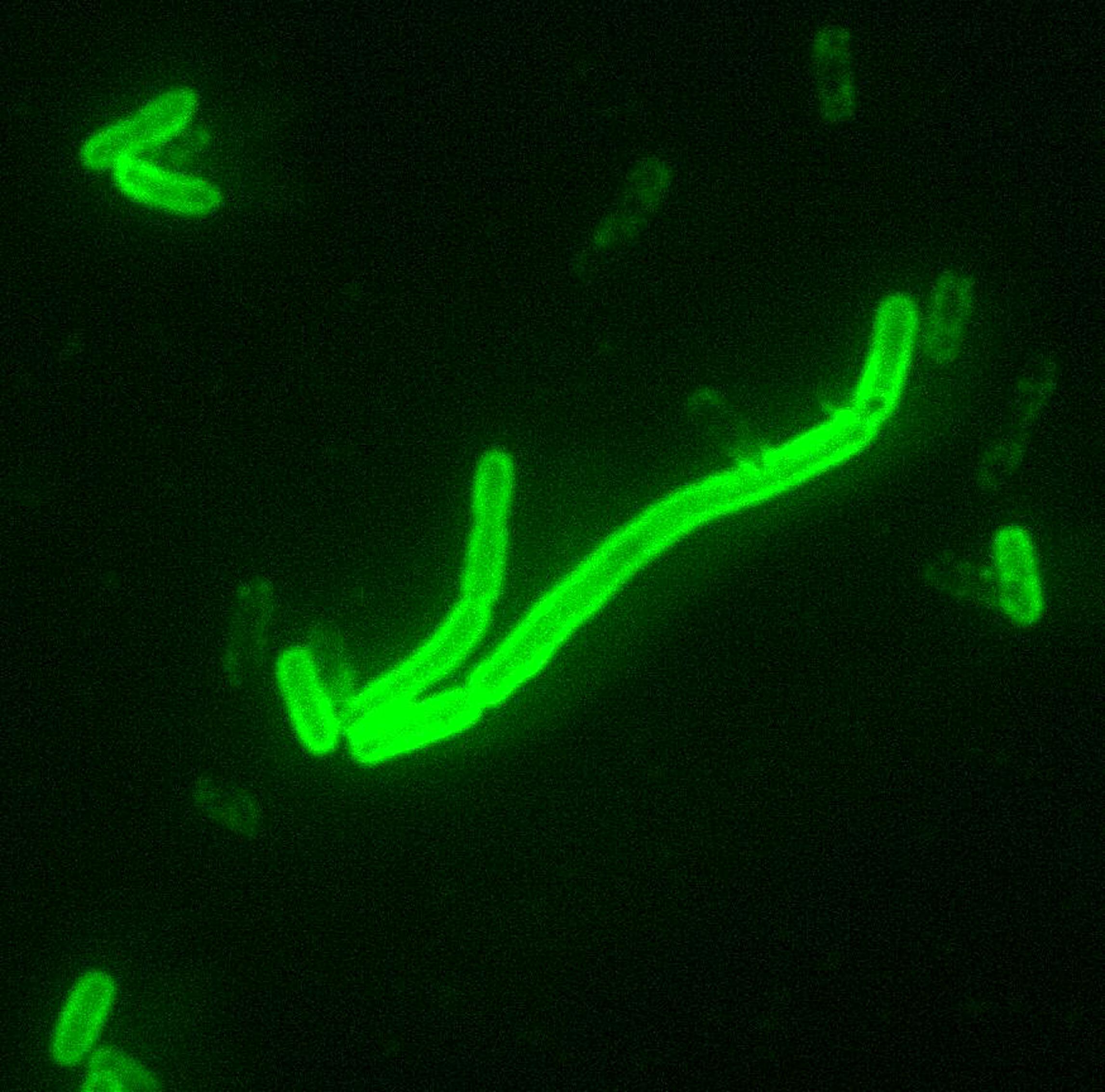

Symptoms of plague are usually non-specific and to definitively diagnose plague, laboratory testing is required.[21] Y. pestis can be identified through both a microscope and by culturing a sample and this is used as a reference standard to confirm that a person has a case of plague.[21] The sample can be obtained from the blood, mucus (sputum), or aspirate extracted from inflamed lymph nodes (buboes).[21] If a person is administered antibiotics before a sample is taken or if there is a delay in transporting the person's sample to a laboratory and/or a poorly stored sample, there is a possibility for false negative results.[21]

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may also be used to diagnose plague, by detecting the presence of bacterial genes such as the pla gene (plasmogen activator) and caf1 gene, (F1 capsule antigen).[21] PCR testing requires a very small sample and is effective for both alive and dead bacteria.[21] For this reason, if a person receives antibiotics before a sample is collected for laboratory testing, they may have a false negative culture and a positive PCR result.[21]

Blood tests to detect antibodies against Y. pestis can also be used to diagnose plague, however, this requires taking blood samples at different periods to detect differences between the acute and convalescent phases of F1 antibody titres.[21]

In 2020, a study about rapid diagnostic tests that detect the F1 capsule antigen (F1RDT) by sampling sputum or bubo aspirate was released.[21] Results show rapid diagnostic F1RDT test can be used for people who have suspected pneumonic and bubonic plague but cannot be used in asymptomatic people. F1RDT may be useful in providing a fast result for prompt treatment and fast public health response as studies suggest that F1RDT is highly sensitive for both pneumonic and bubonic plague. However, when using the rapid test, both positive and negative results need to be confirmed to establish or reject the diagnosis of a confirmed case of plague and the test result needs to be interpreted within the epidemiological context as study findings indicate that although 40 out of 40 people who had the plague in a population of 1000 were correctly diagnosed, 317 people were diagnosed falsely as positive.[21][22][23]

Treatments[edit]

If diagnosed in time, the various forms of plague are usually highly responsive to antibiotic therapy.[6][21] The antibiotics often used are streptomycin, chloramphenicol and tetracycline. Amongst the newer generation of antibiotics, gentamicin and doxycycline have proven effective in monotherapeutic treatment of plague.[6][29] Guidelines on treatment and prophylaxis of plague were published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2021.[7]

The plague bacterium could develop drug resistance and again become a major health threat. One case of a drug-resistant form of the bacterium was found in Madagascar in 1995.[30] Further outbreaks in Madagascar were reported in November 2014[31] and October 2017.[32]

Biological weapon[edit]

The plague has a long history as a biological weapon. Historical accounts from ancient China and medieval Europe details the use of infected animal carcasses, such as cows or horses, and human carcasses, by the Xiongnu/Huns, Mongols, Turks and other groups, to contaminate enemy water supplies. Han dynasty general Huo Qubing is recorded to have died of such contamination while engaging in warfare against the Xiongnu. Plague victims were also reported to have been tossed by catapult into cities under siege.[34]

In 1347, the Genoese possession of Caffa, a great trade emporium on the Crimean peninsula, came under siege by an army of Mongol warriors of the Golden Horde under the command of Jani Beg. After a protracted siege during which the Mongol army was reportedly withering from the disease, they decided to use the infected corpses as a biological weapon. The corpses were catapulted over the city walls, infecting the inhabitants. This event might have led to the transfer of the Black Death via their ships into the south of Europe, possibly explaining its rapid spread.[35]

During World War II, the Japanese Army developed weaponized plague, based on the breeding and release of large numbers of fleas. During the Japanese occupation of Manchuria, Unit 731 deliberately infected Chinese, Korean and Manchurian civilians and prisoners of war with the plague bacterium. These subjects, termed "maruta" or "logs", were then studied by dissection, others by vivisection while still conscious. Members of the unit such as Shiro Ishii were exonerated from the Tokyo tribunal by Douglas MacArthur but 12 of them were prosecuted in the Khabarovsk War Crime Trials in 1949 during which some admitted having spread bubonic plague within a 36-kilometre (22 mi) radius around the city of Changde.[36]

Ishii innovated bombs containing live mice and fleas, with very small explosive loads, to deliver the weaponized microbes, overcoming the problem of the explosive killing the infected animal and insect by the use of a ceramic, rather than metal, casing for the warhead. While no records survive of the actual usage of the ceramic shells, prototypes exist and are believed to have been used in experiments during WWII.[37][38]

After World War II, both the United States and the Soviet Union developed means of weaponising pneumonic plague. Experiments included various delivery methods, vacuum drying, sizing the bacterium, developing strains resistant to antibiotics, combining the bacterium with other diseases (such as diphtheria), and genetic engineering. Scientists who worked in USSR bio-weapons programs have stated that the Soviet effort was formidable and that large stocks of weaponised plague bacteria were produced. Information on many of the Soviet and US projects is largely unavailable. Aerosolized pneumonic plague remains the most significant threat.[39][40][41]

The plague can be easily treated with antibiotics. Some countries, such as the United States, have large supplies on hand if such an attack should occur, making the threat less severe.[42]