Metre (music)

In music, metre (British spelling) or meter (American spelling) refers to regularly recurring patterns and accents such as bars and beats. Unlike rhythm, metric onsets are not necessarily sounded, but are nevertheless implied by the performer (or performers) and expected by the listener.

A variety of systems exist throughout the world for organising and playing metrical music, such as the Indian system of tala and similar systems in Arabic and African music.

Western music inherited the concept of metre from poetry,[1][2] where it denotes the number of lines in a verse, the number of syllables in each line, and the arrangement of those syllables as long or short, accented or unaccented.[1][2] The first coherent system of rhythmic notation in modern Western music was based on rhythmic modes derived from the basic types of metrical unit in the quantitative metre of classical ancient Greek and Latin poetry.[3]

Later music for dances such as the pavane and galliard consisted of musical phrases to accompany a fixed sequence of basic steps with a defined tempo and time signature. The English word "measure", originally an exact or just amount of time, came to denote either a poetic rhythm, a bar of music, or else an entire melodic verse or dance[4] involving sequences of notes, words, or movements that may last four, eight or sixteen bars.

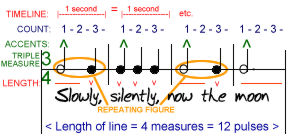

Metre is related to and distinguished from pulse, rhythm (grouping), and beats:

The term metre is not very precisely defined.[1] Stewart MacPherson preferred to speak of "time" and "rhythmic shape",[6] while Imogen Holst preferred "measured rhythm".[7] However, Justin London has written a book about musical metre, which "involves our initial perception as well as subsequent anticipation of a series of beats that we abstract from the rhythm surface of the music as it unfolds in time".[8] This "perception" and "abstraction" of rhythmic bar is the foundation of human instinctive musical participation, as when we divide a series of identical clock-ticks into "tick–tock–tick–tock".[1] "Rhythms of recurrence" arise from the interaction of two levels of motion, the faster providing the pulse and the slower organizing the beats into repetitive groups.[9] In his book The Rhythms of Tonal Music, Joel Lester notes that, "[o]nce a metric hierarchy has been established, we, as listeners, will maintain that organization as long as minimal evidence is present".[10]

"Meter may be defined as a regular, recurring pattern of strong and weak beats. This recurring pattern of durations is identified at the beginning of a composition by a meter signature (time signature). ... Although meter is generally indicated by time signatures, it is important to realize that meter is not simply a matter of notation".[11] A definition of musical metre requires the possibility of identifying a repeating pattern of accented pulses – a "pulse-group" – which corresponds to the foot in poetry. Frequently a pulse-group can be identified by taking the accented beat as the first pulse in the group and counting the pulses until the next accent.[12][1]

Frequently metres can be subdivided into a pattern of duples and triples.[12][1] For example, a 3

4 metre consists of three units of a 2

8 pulse group, and a 6

8 metre consists of two units of a 3

8 pulse group. In turn, metric bars may comprise 'metric groups' - for example, a musical phrase or melody might consist of two bars x 3

4.[13]

The level of musical organisation implied by musical metre includes the most elementary levels of musical form.[6] Metrical rhythm, measured rhythm, and free rhythm are general classes of rhythm and may be distinguished in all aspects of temporality:[14]

Some music, including chant, has freer rhythm, like the rhythm of prose compared to that of verse.[1] Some music, such as some graphically scored works since the 1950s and non-European music such as Honkyoku repertoire for shakuhachi, may be considered ametric.[15] The music term senza misura is Italian for "without metre", meaning to play without a beat, using time (e.g. seconds elapsed on an ordinary clock) if necessary to determine how long it will take to play the bar.[16]

Metric structure includes metre, tempo, and all rhythmic aspects that produce temporal regularity or structure, against which the foreground details or durational patterns of any piece of music are projected.[17] Metric levels may be distinguished: the beat level is the metric level at which pulses are heard as the basic time unit of the piece. Faster levels are division levels, and slower levels are multiple levels.[17] A rhythmic unit is a durational pattern which occupies a period of time equivalent to a pulse or pulses on an underlying metric level.