Popol Vuh

Popol Vuh (also Popul Vuh or Pop Vuj)[1][2] is a text recounting the mythology and history of the Kʼicheʼ people of Guatemala, one of the Maya peoples who also inhabit the Mexican states of Chiapas, Campeche, Yucatan and Quintana Roo, as well as areas of Belize, Honduras and El Salvador.

For other uses, see Popol Vuh (disambiguation).

The Popol Vuh is a foundational sacred narrative of the Kʼicheʼ people from long before the Spanish conquest of the Maya.[3] It includes the Mayan creation myth, the exploits of the Hero Twins Hunahpú and Xbalanqué,[4] and a chronicle of the Kʼicheʼ people.

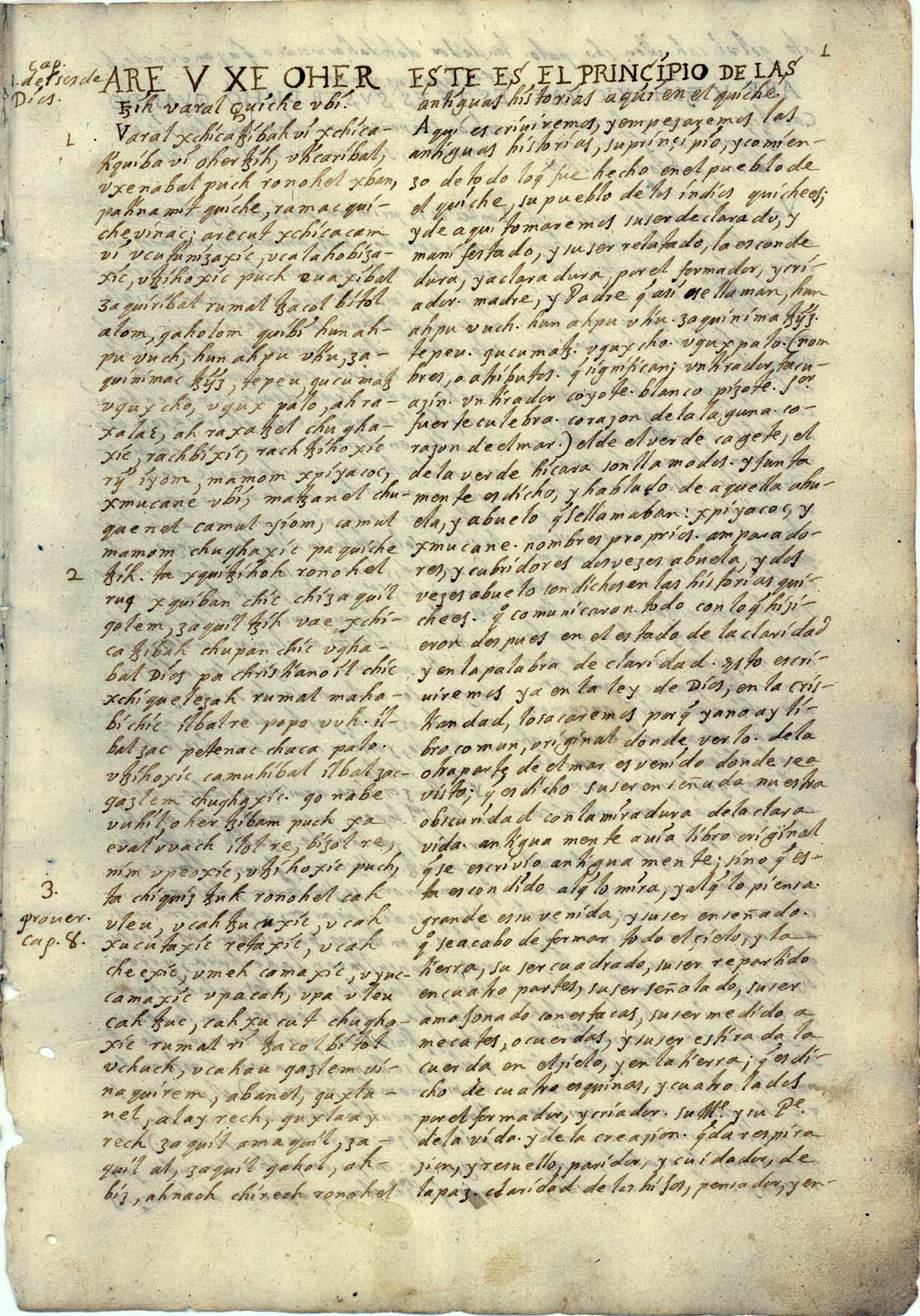

The name "Popol Vuh" translates as "Book of the Community" or "Book of Counsel" (literally "Book that pertains to the mat", since a woven mat was used as a royal throne in ancient Kʼicheʼ society and symbolised the unity of the community).[5] It was originally preserved through oral tradition[6] until approximately 1550, when it was recorded in writing.[7] The documentation of the Popol Vuh is credited to the 18th-century Spanish Dominican friar Francisco Ximénez, who prepared a manuscript with a transcription in Kʼicheʼ and parallel columns with translations into Spanish.[6][8]

Like the Chilam Balam and similar texts, the Popol Vuh is of particular importance given the scarcity of early accounts dealing with Mesoamerican mythologies. After the Spanish conquest, missionaries and colonists destroyed many documents.[9]

History[edit]

Priest Ximénez's manuscript[edit]

In 1701, Francisco Ximénez, priest of Dominicane order, came to Santo Tomás Chichicastenango (also known as Santo Tomás Chuilá). This town was in the Quiché territory and is likely where Ximénez first recorded the work.[10] Ximénez transcribed and translated the account, setting up parallel Kʼicheʼ and Spanish language columns in his manuscript. (He represented the Kʼicheʼ language phonetically with Latin and Parra characters.) In or around 1714, Ximénez incorporated the Spanish content in book one, chapters 2–21 of his Historia de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala de la orden de predicadores. Ximénez's manuscripts were held posthumously by the Dominican Order until General Francisco Morazán expelled the clerics from Guatemala in 1829–30. At that time the Order's documents were taken over largely by the Universidad de San Carlos.

From 1852 to 1855, Moritz Wagner and Carl Scherzer traveled in Central America, arriving in Guatemala City in early May 1854.[11] Scherzer found Ximénez's writings in the university library, noting that there was one particular item "del mayor interés" ('of the greatest interest'). With assistance from the Guatemalan historian and archivist Juan Gavarrete, Scherzer copied (or had a copy made of) the Spanish content from the last half of the manuscript, which he published upon his return to Europe.[12] In 1855, French Abbot Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg also came across Ximénez's manuscript in the university library. However, whereas Scherzer copied the manuscript, Brasseur apparently stole the university's volume and took it back to France.[13] After Brasseur's death in 1874, the Mexico-Guatémalienne collection containing Popol Vuh passed to Alphonse Pinart, through whom it was sold to Edward E. Ayer. In 1897, Ayer decided to donate his 17,000 pieces to The Newberry Library in Chicago, a project that was not completed until 1911. Father Ximénez's transcription-translation of Popol Vuh was among Ayer's donated items.

Priest Ximénez's manuscript sank into obscurity until Adrián Recinos rediscovered it at the Newberry in 1941. Recinos is generally credited with finding the manuscript and publishing the first direct edition since Scherzer. But Munro Edmonson and Carlos López attribute the first rediscovery to Walter Lehmann in 1928.[14] Experts Allen Christenson, Néstor Quiroa, Rosa Helena Chinchilla Mazariegos, John Woodruff, and Carlos López all consider the Newberry volume to be Ximénez's one and only "original."

'Popol Vuh' is also spelled as 'Popol Vuj', its sound in Spanish use is close to German term for 'book': 'buch', in the translation of title meaning by Adrián Recinos, both phonetics and etymology connect to 'People's book', in the line of 'people' used as a synonym for the whole nation or tribe, as in 'Bible, book of Lord's people'.

Modern history[edit]

Modern editions[edit]

Since Brasseur's and Scherzer's first editions, the Popol Vuh has been translated into many other languages besides its original Kʼicheʼ.[37] The Spanish edition by Adrián Recinos is still a major reference, as is Recino's English translation by Delia Goetz. Other English translations[38] include those of Victor Montejo,[39] Munro Edmonson (1985), and Dennis Tedlock (1985, 1996).[40] Tedlock's version is notable because it builds on commentary and interpretation by a modern Kʼicheʼ daykeeper, Andrés Xiloj. Augustín Estrada Monroy published a facsimile edition in the 1970s and Ohio State University has a digital version and transcription online. Modern translations and transcriptions of the Kʼicheʼ text have been published by, among others, Sam Colop (1999) and Allen J. Christenson (2004). In 2018, The New York Times named Michael Bazzett's new translation as one of the ten best books of poetry of 2018.[41] The tale of Hunahpu and Xbalanque has also been rendered as an hour-long animated film by Patricia Amlin.[42][43]

Contemporary culture[edit]

The Popol Vuh continues to be an important part in the belief system of many Kʼicheʼ. Although Catholicism is generally seen as the dominant religion, some believe that many natives practice a syncretic blend of Christian and indigenous beliefs. Some stories from the Popol Vuh continued to be told by modern Maya as folk legends; some stories recorded by anthropologists in the 20th century may preserve portions of the ancient tales in greater detail than the Ximénez manuscript. On August 22, 2012, the Popol Vuh was declared intangible cultural heritage of Guatemala by the Guatemalan Ministry of Culture.[44]

Reflections in Western culture[edit]

Since its rediscovery by Europeans in the nineteenth century, the Popol Vuh has attracted the attention of many creators of cultural works.

Mexican muralist Diego Rivera produced a series of watercolors in 1931 as illustrations for the book.

In 1934, the early avant-garde Franco-American composer Edgard Varèse wrote his Ecuatorial, a setting of words from the Popol Vuh for bass soloist and various instruments.

The planet of Camazotz in Madeleine L'Engle's A Wrinkle in Time (1962) is named for the bat-god of the hero-twins story.

In 1969 in Munich, Germany, keyboardist Florian Fricke—at the time ensconced in Mayan myth—formed a band named Popol Vuh with synth player Frank Fiedler and percussionist Holger Trulzsch. Their 1970 debut album, Affenstunde, reflected this spiritual connection. Another band by the same name, this one of Norwegian descent, formed around the same time, its name also inspired by the Kʼicheʼ writings.

The text was used by German film director Werner Herzog as extensive narration for the first chapter of his movie Fata Morgana (1971). Herzog and Florian Fricke were life long collaborators and friends.

The Argentinian composer Alberto Ginastera began writing his symphonic work Popol Vuh in 1975, but neglected to complete the piece before his death in 1983.

The myths and legends included in Louis L'Amour's novel The Haunted Mesa (1987) are largely based on the Popol Vuh.

The Popol Vuh is referenced throughout Robert Rodriguez's television show From Dusk till Dawn: The Series (2014). In particular, the show's protagonists, the Gecko Brothers, Seth and Richie, are referred to as the embodiment of Hunahpú and Xbalanqué, the hero twins, from the Popol Vuh.

Antecedents in Maya iconography[edit]

Contemporary archaeologists (first of all Michael D. Coe) have found depictions of characters and episodes from Popol Vuh on Mayan ceramics and other art objects (e.g., the Hero Twins, Howler Monkey Gods, the shooting of Vucub-Caquix and, as many believe, the restoration of the Twins' dead father, Hun Hunahpu).[45] The accompanying sections of hieroglyphical text could thus, theoretically, relate to passages from the Popol Vuh. Richard D. Hansen found a stucco frieze depicting two floating figures that might be the Hero Twins[46][47][48][49] at the site of El Mirador.[50]

Following the Twin Hero narrative, mankind is fashioned from white and yellow corn, demonstrating the crop's transcendent importance in Maya culture. To the Maya of the Classic period, Hun Hunahpu may have represented the maize god. Although in the Popol Vuh his severed head is unequivocally stated to have become a calabash, some scholars believe the calabash to be interchangeable with a cacao pod or an ear of corn. In this line, decapitation and sacrifice correspond to harvesting corn and the sacrifices accompanying planting and harvesting.[51] Planting and harvesting also relate to Maya astronomy and calendar, since the cycles of the moon and sun determined the crop seasons.[52]