Preservation (library and archive)

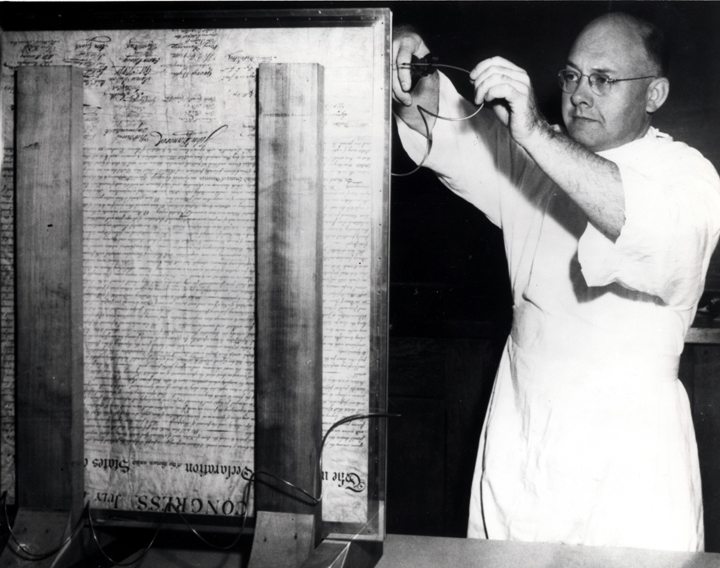

In conservation, library and archival science, preservation is a set of preventive conservation activities aimed at prolonging the life of a record, book, or object while making as few changes as possible. Preservation activities vary widely and may include monitoring the condition of items, maintaining the temperature and humidity in collection storage areas, writing a plan in case of emergencies, digitizing items, writing relevant metadata, and increasing accessibility. Preservation, in this definition, is practiced in a library or an archive by a conservator, librarian, archivist, or other professional when they perceive a collection or record is in need of maintenance.

Preservation should be distinguished from interventive conservation and restoration, which refers to the treatment and repair of individual items to slow the process of decay, or restore them to a usable state.[1] "Preventive conservation" is used interchangeably with "preservation".[2]

Learning the proper methods of preservation is important and most archivists are educated on the subject at academic institutions that specifically cover archives and preservation. In the United States most repositories require archivists to have a degree from an ALA-accredited library school.[33] Similar institutions exist in countries outside the US.

Since 2010, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation has enhanced funding for library and archives conservation education in three major conservation programs.[34] These programs are all part of the Association of North American Graduate Programs in the Conservation of Cultural Property (ANAGPIC).[35]

Another educational resource available to preservationists is the Northeast Document Conservation Center or NEDCC.[36]

The Preservation, Planning and Publications Committee of the Preservation and Reformatting Section (PARS) in the Association for Library Collections & Technical Services has created a Preservation Education Directory of ALA Accredited schools in the U.S. and Canada offering courses in preservation. The directory is updated approximately every three years. The 10th Edition was made available on the ALCTS web site in March 2015.[37]

Additional preservation education is available to librarians through various professional organizations, such as:

Preservation in non-academic facilities[edit]

Public libraries[edit]

Limited, tax-driven funding can often interfere with the ability for public libraries to engage in extensive preservation activities. Materials, particularly books, are often much easier to replace than to repair when damaged or worn. Public libraries usually try to tailor their services to meet the needs and desires of their local communities, which could cause an emphasis on acquiring new materials over preserving old ones. Librarians working in public facilities frequently have to make complicated decisions about how to best serve their patrons. Commonly, public library systems work with each other and sometimes with more academic libraries through interlibrary loan programs. By sharing resources, they are able to expand upon what might be available to their own patrons and share the burdens of preservation across a greater array of systems.

Archival repositories and special collections[edit]

Archival facilities focus specifically on rare and fragile materials. With staff trained in appropriate techniques, archives are often available to many public and private library facilities as an alternative to destroying older materials. Items that are unique, such as photographs, or items that are out of print, can be preserved in archival facilities more easily than in many library settings.[52]

Museums[edit]

Because so many museum holdings are unique, including print materials, art, and other objects, preservationists are often most active in this setting; however, since most holdings are usually much more fragile, or possibly corrupted, conservation may be more necessary than preservation. This is especially common in art museums. Museums typically hold to the same practices led by archival institutions.

History[edit]

Antecedents[edit]

Preservation as a formal profession in libraries and archives dates from the twentieth century, but its philosophy and practice has roots in many earlier traditions.[53]

In many ancient societies, appeals to heavenly protectors were used to preserve books, scrolls and manuscripts from insects, fire and decay.

Legal and ethical issues[edit]

Reformatting, or in any other way copying an item's contents, raises obvious copyright issues. In many cases, a library is allowed to make a limited number of copies of an item for preservation purposes. In the United States, certain exceptions have been made for libraries and archives.[61]

Ethics will play an important role in many aspects of the conservator's activities. When choosing which objects are in need of treatment, the conservator should do what is best for the object in question and not yield to pressure or opinion from outside sources. Conservators should refer to the AIC Code of Ethics and Guidelines for Practice,[62] which states that the conservation professional must "strive to attain the highest possible standards in all aspects of conservation."

One instance in which these decisions may get tricky is when the conservator is dealing with cultural objects. The AIC Code of Ethics and Guidelines for Practice[62] has addressed such concerns, stating "All actions of the conservation professional must be governed by an informed respect for cultural property, its unique character and significance and the people or person who created it." This can be applied in both the care and long-term storage of objects in archives and institutions.

It is important that preservation specialists be respectful of cultural property and the societies that created it, and it is also important for them to be aware of international and national laws pertaining to stolen items. In recent years there has been a rise in nations seeking out artifacts that have been stolen and are now in museums. In many cases museums are working with the nations to find a compromise to balance the need for reliable supervision as well as access for both the public and researchers.[63]

Conservators are not just bound by ethics to treat cultural and religious objects with respect, but also in some cases by law. For example, in the United States, conservators must comply with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). The First Archivists Circle, a group of Native American archivists, has also created Protocols for Native American Archival Materials. The non-binding guidelines are suggestions for libraries and archives with Native American archival materials.

The care of cultural and sacred objects often affects the physical storage or the object. For example, sacred objects of the native peoples of the Western United States are supposed to be stored with sage to ensure their spiritual well-being. The idea of storing an object with plant material is inherently problematic to an archival collection because of the possibility of insect infestation. When conservators have faced this problem, they have addressed it by using freeze-dried sage, thereby meeting both conservation and cultural needs.

Some individuals in the archival community have explored the possible moral responsibility to preserve all cultural phenomena, in regards to the concept of monumental preservation.[64] Other advocates argue that such an undertaking is something that the indigenous or native communities that produce such cultural objects are better suited to perform. Currently, however, many indigenous communities are not financially able to support their own archives and museums. Still, indigenous archives are on the rise in the United States.[65]