Purkinje cell

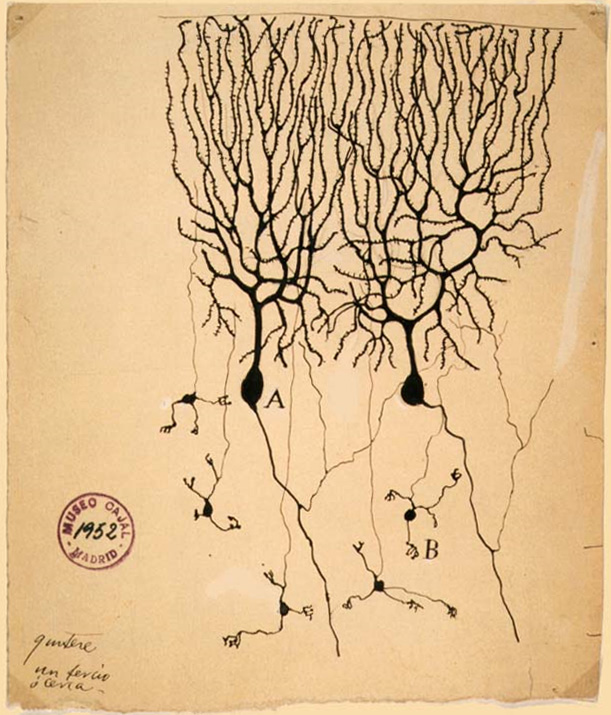

Purkinje cells or Purkinje neurons, named for Czech physiologist Jan Evangelista Purkyně who identified them in 1837, are a unique type of prominent large neurons located in the cerebellar cortex of the brain. With their flask-shaped cell bodies, many branching dendrites, and a single long axon, these cells are essential for controlling motor activity. Purkinje cells mainly release GABA (gamma-aminobutyric acid) neurotransmitter, which inhibits some neurons to reduce nerve impulse transmission. Purkinje cells efficiently control and coordinate the body's motor motions through these inhibitory actions.[2][3]

For the cells of the electrical conduction system of the heart, see Purkinje fibers.Purkinje cell

Often pronounced as /pɜːrˈkɪndʒi/ pur-KIN-jee;[1] but Czech pronunciation is (Czech: [ˈpurkɪɲɛ] cells

Flat dendritic arbor

Inhibitory projection neuron

Cerebellar deep nuclei

Purkinje cells show two distinct forms of electrophysiological activity:

Purkinje cells show spontaneous electrophysiological activity in the form of trains of spikes both sodium-dependent and calcium-dependent. This was initially shown by Rodolfo Llinas (Llinas and Hess (1977) and Llinas and Sugimori (1980)). P-type calcium channels were named after Purkinje cells, where they were initially encountered (Llinas et al. 1989), which are crucial in cerebellar function. Activation of the Purkinje cell by climbing fibers can shift its activity from a quiet state to a spontaneously active state and vice versa, serving as a kind of toggle switch.[24] These findings have been challenged by a study suggesting that such toggling by climbing-fiber inputs occurs predominantly in anaesthetized animals and that Purkinje cells in awake behaving animals, in general, operate almost continuously in the upstate.[25] But this latter study has itself been challenged[26] and Purkinje cell toggling has since been observed in awake cats.[27] A computational model of the Purkinje cell has shown intracellular calcium computations to be responsible for toggling.[28]

Findings have suggested that Purkinje cell dendrites release endocannabinoids that can transiently downregulate both excitatory and inhibitory synapses.[29] The intrinsic activity mode of Purkinje cells is set and controlled by the sodium-potassium pump.[30] This suggests that the pump might not be simply a homeostatic, "housekeeping" molecule for ionic gradients. Instead, it could be a computation element in the cerebellum and the brain.[31] Indeed, a mutation in the Na+

-K+

pump causes rapid onset dystonia parkinsonism; its symptoms indicate that it is a pathology of cerebellar computation.[32]

Furthermore, using the poison ouabain to block Na+

-K+

pumps in the cerebellum of a live mouse induces ataxia and dystonia.[33] Numerical modeling of experimental data suggests that, in vivo, the Na+

-K+

pump produces long quiescent punctuations (>> 1 s) to Purkinje neuron firing; these may have a computational role.[34] Alcohol inhibits Na+

-K+

pumps in the cerebellum and this is likely how it corrupts cerebellar computation and body co-ordination.[35][36]

Clinical significance[edit]

In humans, Purkinje cells can be harmed by a variety of causes: toxic exposure, e.g. to alcohol or lithium; autoimmune diseases; genetic mutations causing spinocerebellar ataxias, gluten ataxia, Unverricht-Lundborg disease, or autism; and neurodegenerative diseases that are not known to have a genetic basis, such as the cerebellar type of multiple system atrophy or sporadic ataxias.[37][38]

Gluten ataxia is an autoimmune disease triggered by the ingestion of gluten.[39] The death of Purkinje cells as a result of gluten exposure is irreversible. Early diagnosis and treatment with a gluten-free diet can improve ataxia and prevent its progression.[37][40] Less than 10% of people with gluten ataxia present any gastrointestinal symptom, yet about 40% have intestinal damage.[40] It accounts for 40% of ataxias of unknown origin and 15% of all ataxias.[40]

The neurodegenerative disease spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1) is caused by an unstable polyglutamine expansion within the Ataxin 1 protein. This defect in Ataxin 1 protein causes impairment of mitochondria in Purkinje cells, leading to premature degeneration of the Purkinje cells.[41] As a consequence, motor coordination declines and eventually death ensues.

Some domestic animals can develop a condition where the Purkinje cells begin to atrophy shortly after birth, called cerebellar abiotrophy. It can lead to symptoms such as ataxia, intention tremors, hyperreactivity, lack of menace reflex, stiff or high-stepping gait, apparent lack of awareness of foot position (sometimes standing or walking with a foot knuckled over), and a general inability to determine space and distance.[42] A similar condition known as cerebellar hypoplasia occurs when Purkinje cells fail to develop in utero or die off before birth.

The genetic conditions ataxia telangiectasia and Niemann Pick disease type C, as well as cerebellar essential tremor, involve the progressive loss of Purkinje cells.

In Alzheimer's disease, spinal pathology is sometimes seen, as well as loss of dendritic branches of the Purkinje cells.[43] Purkinje cells can also be damaged by the rabies virus as it migrates from the site of infection in the periphery to the central nervous system.[44]

Etymology[edit]

Purkinje cells are named after the Czech scientist Jan Evangelista Purkyně, who discovered them in 1839.