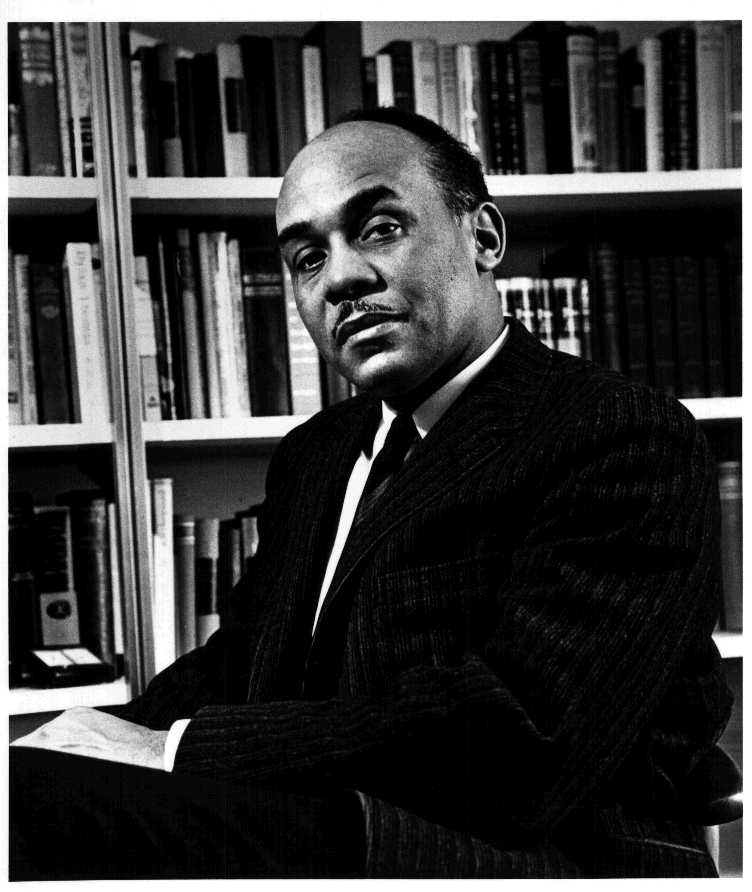

Ralph Ellison

Ralph Ellison (March 1, 1913[a] – April 16, 1994) was an American writer, literary critic, and scholar best known for his novel Invisible Man, which won the National Book Award in 1953.[2]

Ralph Ellison

Ralph Waldo Ellison

March 1, 1913

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, U.S.

April 16, 1994 (aged 81)

New York City, U.S.

Writer

Essay, criticism, novel, short story

Invisible Man (1953)

- National Book Award (1953)

- National Medal of Arts (1985)

Ellison wrote Shadow and Act (1964), a collection of political, social, and critical essays, and Going to the Territory (1986).[3] The New York Times dubbed him "among the gods of America's literary Parnassus".[4]

A posthumous novel, Juneteenth, was published after being assembled from voluminous notes Ellison left upon his death.

Early life[edit]

Ralph Waldo Ellison, named after Ralph Waldo Emerson,[5] was born in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, to Lewis Alfred Ellison and Ida Millsap, on March 1, 1913. He was the second of three sons; firstborn Alfred died in infancy, and younger brother Herbert Maurice (or Millsap) was born in 1916.[1] Lewis Alfred Ellison, a small-business owner and a construction foreman, died in 1916, after work-related injury and a failed operation.[5][6] The elder Ellison loved literature, and doted on his children. Ralph later discovered, as an adult, that his father had hoped he would grow up to be a poet.

In 1921, Ellison's mother and her children moved to Gary, Indiana, where she had a brother.[7] According to Ellison, his mother felt that "my brother and I would have a better chance of reaching manhood if we grew up in the north." When she did not find a job and her brother lost his, the family returned to Oklahoma, where Ellison worked as a busboy, a shoeshine boy, hotel waiter, and a dentist's assistant.[7] From the father of a neighborhood friend, he received free lessons for playing trumpet and alto saxophone, and would go on to become the school bandmaster.[7]

Ida remarried three times after Lewis died.[b] However, the family life was precarious, and Ralph worked various jobs during his youth and teens to assist with family support. While attending Douglass High School, he also found time to play on the school's football team.[6] He graduated from high school in 1931. He worked for a year, and found the money to make a down payment on a trumpet, using it to play with local musicians, and to take further music lessons. At Douglass, he was influenced by principal Inman E. Page and his daughter, music teacher Zelia N. Breaux.[6]

At Tuskegee Institute[edit]

Ellison applied twice for admission to Tuskegee Institute, the prestigious all-black university in Alabama founded by Booker T. Washington.[7] He was finally admitted in 1933 for lack of a trumpet player in its orchestra.[7] Ellison hopped freight trains to get to Alabama, and was soon to find out that the institution was no less class-conscious than white institutions generally were.[7]

Ellison's outsider position at Tuskegee "sharpened his satirical lens," critic Hilton Als believes: "Standing apart from the university's air of sanctimonious Negritude enabled him to write about it." In passages of Invisible Man, "he looks back with scorn and despair on the snivelling ethos that ruled at Tuskegee."[7]

Tuskegee's music department was perhaps the most renowned department at the school,[8] headed by composer William L. Dawson. Ellison also was guided by the department's piano instructor, Hazel Harrison. While he studied music primarily in his classes, he spent his free time in the library with modernist classics. He cited reading T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land as a major awakening moment.[9] In 1934, he began to work as a desk clerk at the university library, where he read James Joyce and Gertrude Stein. Librarian Walter Bowie Williams enthusiastically let Ellison share in his knowledge.[7]

A major influence upon Ellison was English teacher Morteza Drexel Sprague, to whom Ellison later dedicated his essay collection Shadow and Act. He opened Ellison's eyes to "the possibilities of literature as a living art" and to "the glamour he would always associate with the literary life."[7] Through Sprague, Ellison became familiar with Fyodor Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment and Thomas Hardy's Jude the Obscure, identifying with the "brilliant, tortured anti-heroes" of those works.[7]

As a child, Ellison evidenced what would become a lifelong interest in audio technology, starting by taking apart and rebuilding radios, and later moving on to constructing and customizing elaborate hi-fi stereo systems as an adult. He discussed this passion in a December 1955 essay, "Living With Music", in High Fidelity magazine.[10] Ellison scholar John S. Wright contends that this deftness with the ins-and-outs of electronic devices went on to inform Ellison's approach to writing and the novel form.[11] Ellison remained at Tuskegee until 1936, and decided to leave before completing the requirements for a degree.[6]

Later years[edit]

In 1962, the futurist Herman Kahn recruited Ellison as a consultant to the Hudson Institute in an attempt to broaden its scope beyond defense-related research.[16]

In 1964, Ellison published Shadow and Act, a collection of essays, and began to teach at Bard College, Rutgers University and Yale University, while continuing to work on his novel. The following year, a Book Week poll of 200 critics, authors, and editors was released that proclaimed Invisible Man the most important novel since World War II.[17]

In 1967, Ellison experienced a major house fire at his summer home in Plainfield, Massachusetts, in which he claimed more than 300 pages of his second novel manuscript were lost. A perfectionist regarding the art of the novel, Ellison had said in accepting his National Book Award for Invisible Man that he felt he had made "an attempt at a major novel" and, despite the award, he was unsatisfied with the book.[18] Ellison ultimately wrote more than 2,000 pages of this second novel but never finished it.[19]

Ellison died on April 16, 1994, of pancreatic cancer and was interred in a crypt at Trinity Church Cemetery and Mausoleum[20] in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Upper Manhattan.

Legacy and posthumous publications[edit]

After Ellison's death, more manuscripts were discovered in his home, resulting in the publication of Flying Home and Other Stories in 1996. In 1999, his second novel, Juneteenth, was published under the editorship of John F. Callahan, a professor at Lewis & Clark College and Ellison's literary executor. It was a 368-page condensation of more than 2,000 pages written by Ellison over a period of 40 years.[27] All the manuscripts of this incomplete novel were published collectively on January 26, 2010, by Modern Library, under the title Three Days Before the Shooting...[28]

On February 18, 2014, the USPS issued a 91¢ stamp honoring Ralph Ellison in its Literary Arts series.[29][30]

A park on 150th Street and Riverside Drive in Harlem (near 730 Riverside Drive, Ellison's principal residence from the early 1950s until his death) was dedicated to Ellison on May 1, 2003. In the park stands a 15 by 8-foot bronze slab with a "cut-out man figure" inspired by his book Invisible Man.[31]