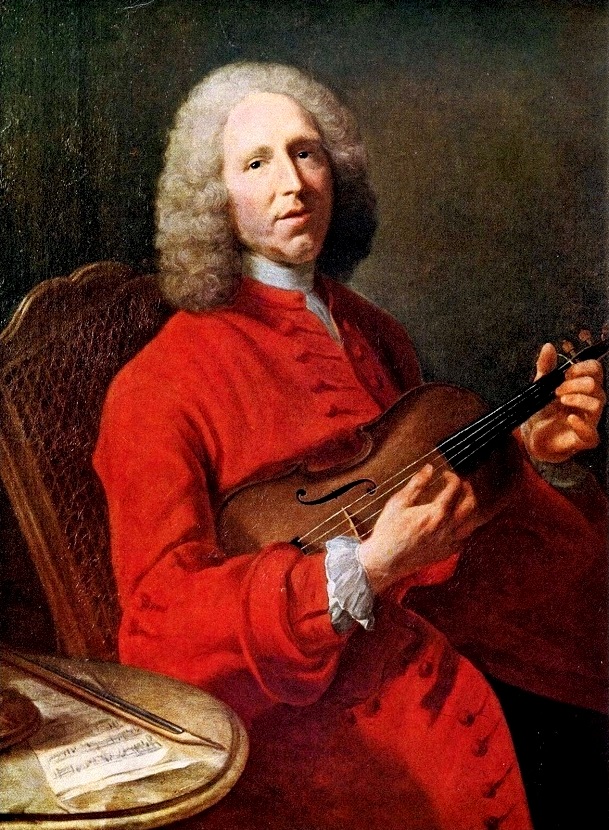

Jean-Philippe Rameau

Jean-Philippe Rameau (French: [ʒɑ̃filip ʁamo]; 25 September 1683 – 12 September 1764) was a French composer and music theorist. Regarded as one of the most important French composers and music theorists of the 18th century,[1] he replaced Jean-Baptiste Lully as the dominant composer of French opera and is also considered the leading French composer of his time for the harpsichord, alongside François Couperin.[2]

"Rameau" redirects here. For other uses, see Rameau (disambiguation).Little is known about Rameau's early years. It was not until the 1720s that he won fame as a major theorist of music with his Treatise on Harmony (1722) and also in the following years as a composer of masterpieces for the harpsichord, which circulated throughout Europe. He was almost 50 before he embarked on the operatic career on which his reputation chiefly rests today. His debut, Hippolyte et Aricie (1733), caused a great stir and was fiercely attacked by the supporters of Lully's style of music for its revolutionary use of harmony. Nevertheless, Rameau's pre-eminence in the field of French opera was soon acknowledged, and he was later attacked as an "establishment" composer by those who favoured Italian opera during the controversy known as the Querelle des Bouffons in the 1750s. Rameau's music had gone out of fashion by the end of the 18th century, and it was not until the 20th that serious efforts were made to revive it. Today, he enjoys renewed appreciation with performances and recordings of his music ever more frequent.

Music[edit]

General character of Rameau's music[edit]

Rameau's music is characterised by the exceptional technical knowledge of a composer who wanted above all to be renowned as a theorist of the art. Nevertheless, it is not solely addressed to the intelligence, and Rameau himself claimed, "I try to conceal art with art." The paradox of this music was that it was new, using techniques never known before, but it took place within the framework of old-fashioned forms. Rameau appeared revolutionary to the Lullyistes, disturbed by complex harmony of his music; and reactionary to the philosophes, who only paid attention to its content and who either would not or could not listen to the sound it made. The incomprehension Rameau received from his contemporaries stopped him from repeating such daring experiments as the second Trio des Parques in Hippolyte et Aricie, which he was forced to remove after a handful of performances because the singers had been either unable or unwilling to execute it correctly.

Rameau's musical works[edit]

Rameau's musical works may be divided into four distinct groups,[32] which differ greatly in importance: a few cantatas; a few motets for large chorus; some pieces for solo harpsichord or harpsichord accompanied by other instruments; and, finally, his works for the stage, to which he dedicated the last thirty years of his career almost exclusively. Like most of his contemporaries, Rameau often reused melodies that had been particularly successful, but never without meticulously adapting them; they are not simple transcriptions. Besides, no borrowings have been found from other composers, although his earliest works show the influence of other music. Rameau's reworkings of his own material are numerous; e.g., in Les Fêtes d'Hébé, we find L'Entretien des Muses, the Musette, and the Tambourin, taken from the 1724 book of harpsichord pieces, as well as an aria from the cantata Le Berger Fidèle.[33]

Notes

Sources

Sheet music