Hippocampus

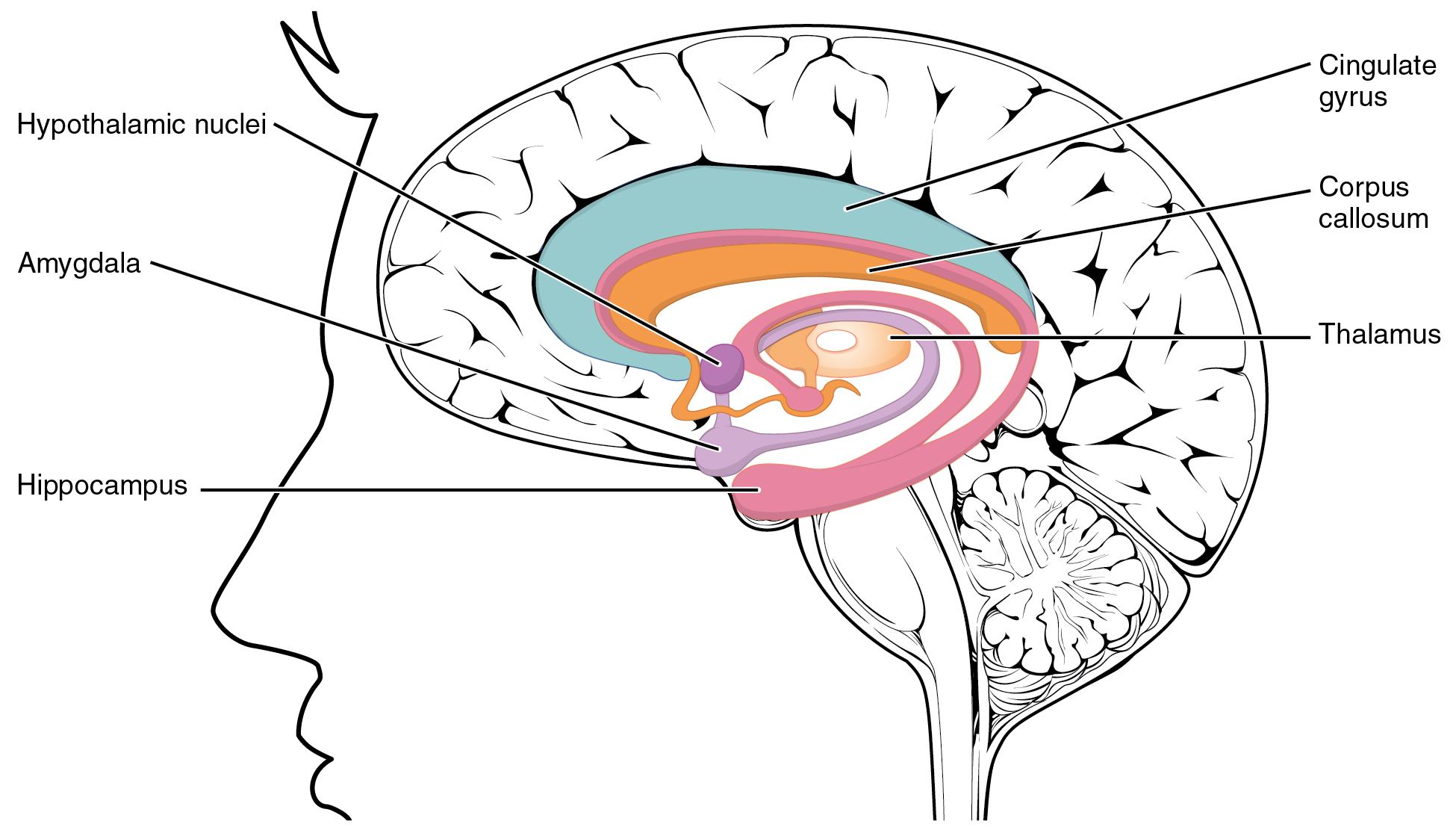

The hippocampus (pl.: hippocampi; via Latin from Greek ἱππόκαμπος, 'seahorse') is a major component of the brain of humans and other vertebrates. Humans and other mammals have two hippocampi, one in each side of the brain. The hippocampus is part of the limbic system, and plays important roles in the consolidation of information from short-term memory to long-term memory, and in spatial memory that enables navigation. The hippocampus is located in the allocortex, with neural projections into the neocortex, in humans[1][2][3] as well as other primates.[4] The hippocampus, as the medial pallium, is a structure found in all vertebrates.[5] In humans, it contains two main interlocking parts: the hippocampus proper (also called Ammon's horn), and the dentate gyrus.[6][7]

This article is about the section in the brain. For the fish genus Hippocampus, see Seahorse. For the mythological creature Hippocampus, see Hippocampus (mythology). For other uses, see Hippocampus (disambiguation).Hippocampus

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#0__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#0__subtitleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

In Alzheimer's disease (and other forms of dementia), the hippocampus is one of the first regions of the brain to suffer damage;[8] short-term memory loss and disorientation are included among the early symptoms. Damage to the hippocampus can also result from oxygen starvation (hypoxia), encephalitis, or medial temporal lobe epilepsy. People with extensive, bilateral hippocampal damage may experience anterograde amnesia: the inability to form and retain new memories.

Since different neuronal cell types are neatly organized into layers in the hippocampus, it has frequently been used as a model system for studying neurophysiology. The form of neural plasticity known as long-term potentiation (LTP) was initially discovered to occur in the hippocampus and has often been studied in this structure. LTP is widely believed to be one of the main neural mechanisms by which memories are stored in the brain.

In rodents as model organisms, the hippocampus has been studied extensively as part of a brain system responsible for spatial memory and navigation. Many neurons in the rat and mouse hippocampus respond as place cells: that is, they fire bursts of action potentials when the animal passes through a specific part of its environment. Hippocampal place cells interact extensively with head direction cells, whose activity acts as an inertial compass, and conjecturally with grid cells in the neighboring entorhinal cortex.

Relation to limbic system[edit]

The term limbic system was introduced in 1952 by Paul MacLean[15] to describe the set of structures that line the deep edge of the cortex (Latin limbus meaning border): These include the hippocampus, cingulate cortex, olfactory cortex, and amygdala. Paul MacLean later suggested that the limbic structures comprise the neural basis of emotion. The hippocampus is anatomically connected to parts of the brain that are involved with emotional behavior – the septum, the hypothalamic mammillary body, and the anterior nuclear complex in the thalamus, and is generally accepted to be part of the limbic system.[16]

Function[edit]

Theories of hippocampal functions[edit]

Over the years, three main ideas of hippocampal function have dominated the literature: response inhibition, episodic memory, and spatial cognition. The behavioral inhibition theory (caricatured by John O'Keefe and Lynn Nadel as "slam on the brakes!")[40] was very popular up to the 1960s. It derived much of its justification from two observations: first, that animals with hippocampal damage tend to be hyperactive; second, that animals with hippocampal damage often have difficulty learning to inhibit responses that they have previously been taught, especially if the response requires remaining quiet as in a passive avoidance test. British psychologist Jeffrey Gray developed this line of thought into a full-fledged theory of the role of the hippocampus in anxiety.[41] The inhibition theory is currently the least popular of the three.[42]

The second major line of thought relates the hippocampus to memory. Although it had historical precursors, this idea derived its main impetus from a famous report by American neurosurgeon William Beecher Scoville and British-Canadian neuropsychologist Brenda Milner[43] describing the results of surgical destruction of the hippocampi when trying to relieve epileptic seizures in an American man Henry Molaison,[44] known until his death in 2008 as "Patient H.M." The unexpected outcome of the surgery was severe anterograde and partial retrograde amnesia; Molaison was unable to form new episodic memories after his surgery and could not remember any events that occurred just before his surgery, but he did retain memories of events that occurred many years earlier extending back into his childhood. This case attracted such widespread professional interest that Molaison became the most intensively studied subject in medical history.[45] In the ensuing years, other patients with similar levels of hippocampal damage and amnesia (caused by accident or disease) have also been studied, and thousands of experiments have studied the physiology of activity-driven changes in synaptic connections in the hippocampus. There is now universal agreement that the hippocampi play some sort of important role in memory; however, the precise nature of this role remains widely debated.[46][47] A recent theory proposed – without questioning its role in spatial cognition – that the hippocampus encodes new episodic memories by associating representations in the newborn granule cells of the dentate gyrus and arranging those representations sequentially in the CA3 by relying on the phase precession generated in the entorhinal cortex.[48]

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#1__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#1__subtextDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#1__answer--0DEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#1__answer--1DEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#1__answer--2DEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#1__answer--3DEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#1__answer--4DEEZ_NUTS$_$_$