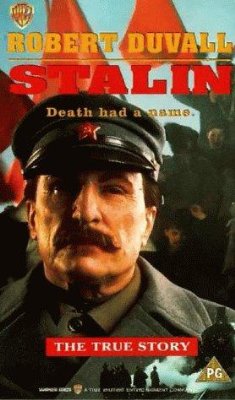

Stalin (1992 film)

Stalin is a 1992 American political drama television film starring Robert Duvall as Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. Produced by HBO and directed by Ivan Passer, it tells the story of Stalin's rise to power until his death and spans the period from 1917 to 1953. Owing to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev's policies of glasnost and perestroika, producer Mark Carliner was able to receive permission to film in the Kremlin, becoming the first feature film to do so.

Stalin

United States

English

Mark Carliner

Peter Davies

172 minutes

November 21, 1992

Filming was done in Budapest and the Soviet Union with extraordinary access to Soviet historic sites in the weeks before its dissolution. Although the film was almost entirely shot on location and producer Mark Carliner insisted that the film "reflect the truth", several scholars and historians commented that the film focused less on history and more on Stalin's character. This was seen as a flaw by many film critics, while still praising Robert Duvall's performance as Stalin. Julia Ormond's portrayal of Nadezhda Alliluyeva and Vilmos Zsigmond's camera work were also singled out for praise.

The film received several accolades, including four Primetime Emmy Awards (including Outstanding Made for Television Movie) and three Golden Globe Awards.

Synopsis[edit]

Svetlana Alliluyeva, daughter of Joseph Stalin, recounts her father returning from his Siberian exile to enlist in World War I, but being rejected for service. Stalin continues to fight against the tsar, and in 1917, stands at the train platform with his comrades awaiting the return of Vladimir Lenin. The October Revolution results in a new government being formed in Russia under the leadership of Lenin. The young Nadezhda Alliluyeva is hired as secretary for the new Bolshevik leaders. She admires Stalin's exploits during the revolution and marries him, ignoring his weaknesses of character, such as his distrust of other people.

Stalin is resolute and ruthless, having several officers murdered, which prompts Leon Trotsky to complain to Lenin. To the intellectual Trotsky's displeasure, Lenin defends Stalin and his methods. A power struggle develops between him and Stalin over Lenin's legacy. When Lenin suffers a stroke, Stalin uses every opportunity to expel Trotsky and position himself as his successor. He surrounds himself with loyal companions, such as Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev. After Lenin's death, Stalin becomes the new ruler of the Soviet Union. As one of his first acts, he exiles Trotsky from the country.

Stalin begins dekulakization and crushes all resistance with the secret police which undergoes several internal purges, eventually being headed by Lavrentiy Beria. When Stalin's son from his first marriage Yakov Dzhugashvili attempts suicide over his father's refusal to approve his marriage to a Jew, Nadezhda is struck by her husband's growing inhumanity and returns to her parents' home. She considers leaving him but fears for her parents' fates if she does so, eventually returning to Moscow. During her train journey through the country, Nadezhda sees many farmers being shot or deported and defies her husband at a boisterous celebration. Stalin chastises and deliberately humiliates her, causing Nadezhda to leave and commit suicide. Her loss leaves Stalin in silent grief and anger for "betraying" him. He pushes ahead with a massive industrialization of the Soviet Union with ever new large-scale projects in order to develop the country into a world power.

Resistance to Stalin begins building up in Leningrad, spurred by the local official Sergei Kirov. Stalin sees him as a competitor and successfully eliminates him. After the assassination, he uses show trials to stage the Great Purge, killing and imprisoning many of his critics and former allies, who are forced to denounce each other to save themselves. Nikolai Bukharin notes the growing darkness over the country and expresses doubt about the legitimacy of the trials. Amongst those eventually killed are Bukharin himself, Sergo Ordzhonikidze (Stalin's close friend), Zinoviev, and Kamenev.

Stalin watches the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany, admiring Hitler's will to get what he wants. He adamantly refuses to believe that Hitler will invade the Soviet Union and is shocked when it happens in June 1941. After Stalin has digested the shock, he prepares a counter-offensive, vowing not to surrender. His son, now an artillery officer, is captured by the Germans, who Stalin denies knowledge of. After the victory over Germany, Stalin withdraws more and more from the public eye and sees only conspiracies even amongst his inner circle. His only regret on his deathbed remains Nadezhda's suicide.

Svetlana Alliluyeva visits her father's body lying in state, while the film notes that Stalin's crimes caused the deaths of millions of Soviet citizens.

Background[edit]

Inspiration[edit]

The idea of a film about Stalin occurred during an American Broadcasting Company (ABC) broadcast of the TV film Disaster at Silo 7 produced by Mark Carliner, which was seen by a member of an official Russian delegation during their stay in the United States. Enthusiastic about the anti-nuclear topic, she invited Carliner to Russia for several seminars and demonstrations. When Carliner visited the country, the film was broadcast on Russian television and well received. This later enabled Carliner to obtain filming permits for original locations.[3]

Carliner had studied Russian history at Princeton University, and credits his Russian heritage for his motivation to film the movie.[3][4] He presented the project to ABC and was rejected on the grounds that it was "too expensive and too risky".[5] Only the chairman of the cable channel Home Box Office (HBO) Michael J. Fuchs, who had considered making a film about Stalin, agreed to take on the project. It took two more years of research with the assistance of Soviet officials specialising in Stalin's era to access to archives and historical recordings, to write the script.[3]

In July 1991, the project was presented as "the first honest, very personal reckoning with the controversial, dictatorial godfather of the Soviet Union".[6] Carliner emphasized that it would not only be a historical biography, but also a gangster film.[7] According to various sources, a production budget of between 9.5 million[8] and 10 million[1][2] US dollars was allocated for the film.

Casting and director[edit]

According to Carliner, Al Pacino was among several actors who expressed an interest in the lead, which eventually went to Robert Duvall.[9] Duvall had turned down the offer to play Stalin in Andrei Konchalovsky's feature film The Inner Circle three months earlier, which is said to have been due to different salary expectations.[10][11] When Duvall was offered the lead by Carliner, he agreed to take up the role.[11] Carliner noted that Duvall was not his first choice, as his body constitution was more similar to Lenin's.[9]

Duvall was keen to have Czech director Ivan Passer direct and fought for his appointment. Although the producers didn't like it, Passer was eventually hired very late into the project. Having fled his native country during the Prague Spring, Passer had a special relationship with the project.[5]

Reception[edit]

Russian premiere[edit]

Owing to the attempted coup, Boris Yeltsin asked the filmmakers to have the film shown on November 7, 1992, in the cinema of the DOM Cultural Center in Moscow before it was broadcast on US television on November 21, 1992.[11] The date was deliberately chosen as it was the 75th anniversary of the October Revolution.[21] Even before the premiere, isolated scenes were shown on Russian television. Nikolai Pavlov, a member of the opposition leadership committee of the National Salvation Front, strongly criticized the film on the grounds that it "oversimplified everything" and there was nothing left of Stalin except a "dissolute sadist and executioner craving for power".[11] Yeltsin was undeterred and demanded that the film be seen by 1,000 celebrities and senior figures in the Russian government.[12] Like Gorbachev, he himself stayed away from the premiere. However, Vice President Alexander Rutskoy and former Soviet US ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin did appear.[21]

At the beginning of the event, Stalin biographer and historian Dmitri Volkogonov explained the film, noting both the historical context and that the film was merely "an American take on Stalin".[21] The film opened with laughter as viewers watched the opening scene, which allegedly portrayed Stalin in Siberia, with local Muscovites immediately recognising a suburb of Moscow. As the film progressed, and the realization that Stalin's crimes were mostly left out, the audience grumbled, and the film ended with "shallow clapping".[21]

When asked about their opinion of the film, people gave different answers depending on whether they sympathized with Stalin or thought he was a criminal. Russian politicians saw the film as more of a "political thriller that reduces Stalin to a gangster and hangman".[8] Many viewers felt that one should have focused less on Stalin's life and more on his crimes.[21] Rada Adzhubei, daughter of Nikita Khrushchev, found it "good that such films are shown" and saw it "with pleasure".[8] A senior adviser to Ruzkoi opined that the film was seen as "useful for Americans, useless for Russians".[27] Some said the film was a "farce, a fake [...] American propaganda to tear up the country", while others criticized it for romanticizing Stalin. The film was characterized as "artificial and primitive", and a "parody".[8] Overall, it was stated that one could “not make a good film about Stalin or Hitler” because “regardless of what one does in the film”, one could never “do justice to reality”.[21] However, almost everyone were satisfied with Duvall's portrayal and the stunning original locations.[21]

Duvall, who usually speaks with a slight Southern accent,[10] said before the premiere that his interpretation of a Georgian accent would probably cause "a lot of frowns at the premiere".[16] After the premiere, Russian film producers offered Duvall to star in other possible Russian films about Lenin and Trotsky; Duvall declined.[16]

American reaction[edit]

Critics acknowledged the effort put into the film as well as the high production budget. Tom Shales of The Washington Post praised the "impressive aspects" and "powerful scenes" of the film[28] while Lon Grahnke labelled it a "formidable epic".[29] Lee Winfrey of Inquirer TV compliments the film for its "textbook examples of how to do drama".[5]

The film's cinematography was also praised. Vilmos Zsigmond's camera work was singled out for special mention. He matched his color scheme to the characters' feelings about life, initially showing colorful images meant to illustrate the "very happy and optimistic" hopes after the revolution. However, as the film progresses, the color choices diminish, leaving only black and white at the end.[5] This was recognized as "lavish"[30] and "beautifully filmed" and "magnificently staged".[31]

The film was also said to have a "very good" color scheme. This would be primarily due to the exterior shots, which offer the film a "look, fullness, unpredictability"[30] and "sense of authenticity"[25] The film's "unpredictability"[30] is also a factor, along with Syrewicz's turbulent composition, which is at times overwhelming.[31]

Duvall's performance of Stalin was subjected to criticism. Although a variety of different situations, such as singing, dancing and joking were shown,[12] some felt that Duvall remained "invisible under the mask".[4] Opinions differed as to whether Duvall's acting was hampered by the mask because he could only move his eyes[30] or whether, despite the "expressionless face"[4] and his "mysterious and inscrutable"[31] acting, "no one ever portrayed Stalin more convincingly and forcefully than Duvall".[1] The mask in particular seemed to have an impact on the acting, as there were no spontaneous actions and any moment of hilarity can turn into dead silence. Duvall could only do this due to the mask, which created an "illusion of threat".[12] For others however, the illusion was not present; Sun Sentinel's Scott Hettrick suggests that a major problem with the film is that "once you see Robert Duvall, you see Robert Duvall. But when you see Maximilian Schell, you see Lenin and only realize very late that it is Schell”.[25]

The focus on Stalin's personal life has been considered by some to be the film's "greatest strength and at the same time its main weakness".[1] Almost all film critics took up the "lack of historical context"[28][32] as the greatest point of criticism. While it was not possible to present Stalin's story in a three-hour film,[31] which would require a "long mini-series to capture Stalin in his entirety",[1] a major problem was that the film left the questions it raised unanswered, leaving the viewer unsure of Stalin's true character.[31] John Leonard from the New York Magazine opined that the film was no more than a Forsyte saga, as it seemed more important to show how "Stalin sticks a lighted cigarettes down Nadya's dress and is unkind to his children from both marriages", than to delve into important historical matters.[26]

Press reviews[edit]

Though it's an "ambitious and magnificently expensive project", The New York Times's John J. O'Connor wondered what "could have gone wrong". He put it down to the production process, saying the film was not only "superficial" but also "overly diplomatic" in order to survive in the world market, particularly in Russia. He did, however, commend Duvall, who was "wrapped under acrylic makeup" and "caught in an unrelentingly evil role between The Godfather and Potemkin [...] trying to humanize Stalin".[33]

According to Variety magazine's Tony Scott, Passer's "impressive directing" and Duvall's superb acting, who as a result of the mask had to "convey essences by using shrewd body language", meant the film could fully draw on Stalin's "ruthlessness, his manipulations, [and] his disregard for friendship”, but also claimed that the attempt to understand the Georgian despot through the film failed.[2]

In the Chicago Sun-Times, Lon Grahnke said the film is both a "formidable epic" and a "gloomy and often depressing film that charts a murderer's rise to absolute power". He praised Duvall for struggling to find a "spark of humanity in a cold-blooded creature" and despite his comparable "passive acting" is still "more interesting than his" fellow actors. He also said that in "their dark images, Passer and Zsigmond reflect their Slavic sensibilities and painful memories of their youth in Eastern Europe". He criticized the film for focusing on too many historical facts and exploring the "psychological motives" enough.[29]

Rick Kogan said in the Chicago Tribune that the film failed to depict enough attention to Leon Trotsky and World War II, and therefore couldn't fully present Stalin and the "monster in the man". He also writes that the film's attempt to compress long drawn-out events to create "a more intimate, and therefore more chilling portrait" was "misguided" and only partially successfully. He praised Duvall's "mesmerizing performance" and saw Stalin's wife, Nadezhda Alliluyeva, as "most tragic victim" as she is the only person to whom he is devoted and shows humanity.[23]

"The film is worth watching just for Duvall's acting," Fred Kaplan writes in the Boston Globe, because the rest was just "absolutely stupid" and "trivial". After all, the film has nothing to say other than that Stalin was a monster. He further criticized that the "history is presented almost entirely as a palace intrigue" without going into the background and causes. While praising "Duvall's haunting performance as a Soviet dictator," he also regretted that "the screenplay lacked so much" that Duvall could have alluded to. The film "would only be more tolerable" if it lived up to its own claim of "presenting a compelling anatomy of evil," but even at that it "fails".[32]

David Zurawik wrote in the Baltimore Sun that "HBO had lost its Joseph Stalin somewhere between the script and the screen". The film was "lavishly staged" and had "visually a structure, richness and unpredictability that only exterior shots can offer. But looks aren't everything”. Especially when, in his opinion, only “essential kitchen psychology” was used to characterize Stalin, which depicted his inner life far too simply. He also laments that Duvall was hampered by his mask and could only move his eyes, making his game look absolutely leaden.[30]

In Entertainment Weekly, Michael Sauter opined that Duvall "exhibits a dominant presence as Comrade Stalin" but the human behind it remains hidden "under all the tons of makeup". He also wondered why the "second biggest monster of the century" was so boring.[34]