Sumerian language

Sumerian (Sumerian: 𒅴𒂠, romanized: Emeg̃ir, lit. ''native language'') was the language of ancient Sumer. It is one of the oldest attested languages, dating back to at least 2900 BC. It is a local language isolate that was spoken in ancient Mesopotamia, in the area that is modern-day Iraq.

Sumerian

Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq)

Attested from c. 2900 BC. Went out of vernacular use around 1700 BC; used as a classical language until about 100 AD.[1]

Akkadian, a Semitic language, gradually replaced Sumerian as the primary spoken language in the area c. 2000 BC (the exact date is debated),[4] but Sumerian continued to be used as a sacred, ceremonial, literary and scientific language in Akkadian-speaking Mesopotamian states such as Assyria and Babylonia until the 1st century AD.[5][6] Thereafter, it seems to have fallen into obscurity until the 19th century, when Assyriologists began deciphering the cuneiform inscriptions and excavated tablets that had been left by its speakers.

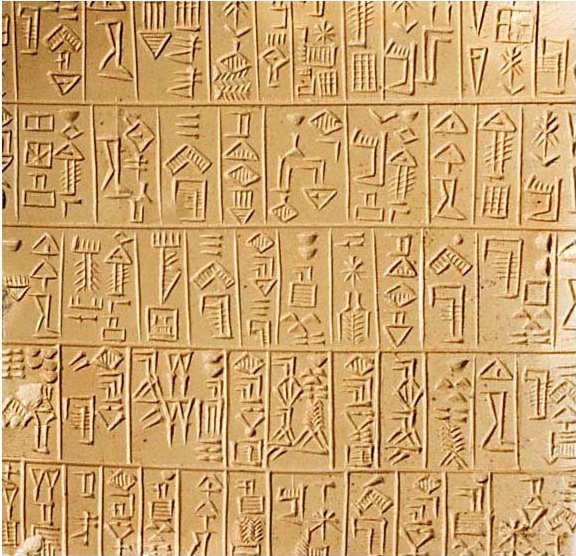

In spite of its extinction, Sumerian exerted a significant impact on the languages of the area. The cuneiform script, originally used for Sumerian, was widely adopted by numerous regional languages such as Akkadian, Elamite, Eblaite, Hittite, Hurrian, Luwian and Urartian; it similarly inspired the Old Persian alphabet which was used to write the eponymous language. The impact was perhaps the greatest on Akkadian whose grammar and vocabulary were significantly influenced by Sumerian.[7]

The history of written Sumerian can be divided into several periods:[9][10][11][12]

The pictographic writing system used during the Proto-literate period (3200 BC – 3000 BC), corresponding to the Uruk III and Uruk IV periods in archeology, was still so rudimentary that there remains some scholarly disagreement about whether the language written with it is Sumerian at all, although it has been argued that there are some, albeit still very rare, cases of phonetic indicators and spelling that show this to be the case.[13] The texts from this period are mostly administrative.[9]

The next period, Archaic Sumerian (3000 BC – 2500 BC), is the first stage of inscriptions that indicate grammatical elements, so the identification of the language is certain. It includes some administrative texts and sign lists from Ur (c. 2800 BC). Texts from Shuruppak and Abu Salabikh from 2600 to 2500 BC (the so-called Fara period or Early Dynastic Period IIIa) are the first to span a greater variety of genres, including not only administrative texts and sign lists, but also incantations, legal and literary texts (including proverbs and early versions of the famous works The Instructions of Shuruppak and The Kesh temple hymn). However, the spelling of grammatical elements remains optional, making the interpretation and linguistic analysis of these texts difficult.[9][14]

The Old Sumerian period (2500-2350 BC) is the first one from which well-understood texts survive. It corresponds mostly to the last part of the Early Dynastic period (ED IIIb) and specifically to the First Dynasty of Lagash, from where the overwhelming majority of surviving texts come. The sources include important royal inscriptions with historical content as well as extensive administrative records.[9] Sometimes included in the Old Sumerian stage is also the Old Akkadian period (c. 2350 BC – c. 2200 BC),[15] during which Mesopotamia, including Sumer, was united under the rule of the Akkadian Empire. At this time Akkadian functioned as the primary official language, but texts in Sumerian (primarily administrative) did continue to be produced as well.[9]

The first phase of the Neo-Sumerian period corresponds to the time of Gutian rule in Mesopotamia; the most important sources come from the autonomous Second Dynasty of Lagash, especially from the rule of Gudea, which has produced extensive royal inscriptions. The second phase corresponds to the unification of Mesopotamia under the Third Dynasty of Ur, which oversaw a "renaissance" in the use of Sumerian throughout Mesopotamia, using it as its sole official written language. There is a wealth of texts greater than from any preceding time – besides the extremely detailed and meticulous administrative records, there are numerous royal inscriptions, legal documents, letters and incantations.[15] In spite of the dominant position of written Sumerian during the Ur III dynasty, it is controversial to what extent it was actually spoken or had already gone extinct in most parts of its empire,[4][16] as there are indications that many scribes[4][17] and even the royal court actually used Akkadian as their main spoken and native language.[17] Evidence has been adduced to the effect that native Sumerian speakers persisted, but only as a minority of the population.[17]

By the Old Babylonian period (c. 2000 – c. 1600 BC), Akkadian had clearly supplanted Sumerian as a spoken language in nearly all of its original territory, whereas Sumerian continued its existence as a liturgical and classical language for religious, artistic and scholarly purposes. In addition, it has been argued that Sumerian persisted as a spoken language at least in a small part of Southern Mesopotamia (Nippur and its surroundings) until as late as 1700 BC.[4] Nonetheless, it seems clear that by far the majority of scribes writing in Sumerian in this point were not native speakers and errors resulting from their Akkadian mother tongue become apparent.[18] For this reason, this period as well as the remaining time during which Sumerian was written are sometimes referred to as the "Post-Sumerian" period.[11] The written language of administration, law and royal inscriptions continued to be Sumerian in the undoubtedly Semitic-speaking successor states of Ur III during the so-called Isin-Larsa period (c. 2000 BC – c. 1750 BC). The Old Babylonian Empire, however, mostly used Akkadian in inscriptions, sometimes adding Sumerian versions.[17][19]

The Old Babylonian period, especially its early part,[9] has produced extremely numerous and varied Sumerian literary texts: myths, epics, hymns, prayers, wisdom literature and letters. In fact, nearly all preserved Sumerian religious and wisdom literature[20] and the overwhelming majority of surviving manuscripts of Sumerian literary texts in general[21][22][23] can be dated to that time, and it is often seen as the "classical age" of Sumerian literature.[24] Conversely, far more literary texts on tablets surviving from the Old Babylonian period are in Sumerian than in Akkadian, even though that time is viewed as the classical period of Babylonian culture and language.[25][26][22] However, it has sometimes been suggested that many or most of these "Old Babylonian Sumerian" texts may be copies of works that were originally composed in the preceding Ur III period or earlier, and some copies or fragments of known compositions or literary genres have indeed been found in tablets of Neo-Sumerian and Old Sumerian provenance.[27][22] In addition, some of the first bilingual Sumerian-Akkadian lexical lists are preserved from that time (although the lists were still usually monolingual and Akkadian translations did not become common until the late Middle Babylonian period)[28] and there are also grammatical texts - essentially bilingual paradigms listing Sumerian grammatical forms and their postulated Akkadian equivalents.[29]

After the Old Babylonian period[11] or, according to some, as early as 1700 BC,[9] the active use of Sumerian declined. Scribes did continue to produce texts in Sumerian at a more modest scale, but generally with interlinear Akkadian translations[30] and only part of the literature known in the Old Babylonian period continued to be copied after its end around 1600 BC.[20] During the Middle Babylonian period, approximately from 1600 to 1000 BC, the Kassite rulers continued to use Sumerian in many of their inscriptions,[31][32] but Akkadian seems to have taken the place of Sumerian as the primary language of texts used for the training of scribes[33] and their Sumerian itself acquires an increasingly artificial and Akkadian-influenced form.[20][34][35] In some cases a text may not even have been meant to be read in Sumerian; instead, it may have functioned as a prestigious way of "encoding" Akkadian via Sumerograms (cf. Japanese kanbun).[34] Nonetheless, the study of Sumerian and copying of Sumerian texts remained an integral part of scribal education and literary culture of Mesopotamia and surrounding societies influenced by it[31][32][36][37][a] and it retained that role until the eclipse of the tradition of cuneiform literacy itself in the beginning of the Common Era. The most popular genres for Sumerian texts after the Old Babylonian period were incantations, liturgical texts and proverbs; most commonly, the classics Lugal-e and An-gim were copied.[20]

Classification[edit]

Sumerian is widely accepted to be a local language isolate.[39][40][41][42] Sumerian was at one time widely held to be an Indo-European language, but that view has been almost universally rejected.[43] Since its decipherment in the early 20th century, scholars have tried to relate Sumerian to a wide variety of languages. Because Sumerian has prestige as the first attested written language, proposals for linguistic affinity sometimes have a nationalistic flavour, leading to attempts to link Sumerian with a range of widely disparate groups such as the Austroasiatic languages,[44] Dravidian languages,[45] Uralic languages such as Hungarian and Finnish,[46][47][48][49] and Sino-Tibetan languages.[50] Turkish nationalists have claimed that Sumerian was a Turkic language as part of the Sun language theory.[51][52] Additionally, long-range proposals have attempted to include Sumerian in broad macrofamilies.[53][54] Such proposals enjoy virtually no support among modern linguists, Sumerologists and Assyriologists and are typically seen as fringe theories.[55]

It has also been suggested that the Sumerian language descended from a late prehistoric creole language (Høyrup 1992).[56] However, no conclusive evidence, only some typological features, can be found to support Høyrup's view. A more widespread hypothesis posits a Proto-Euphratean language that preceded Sumerian in Mesopotamia and exerted an areal influence on it, especially in the form of polysyllabic words that appear "un-Sumerian"—making them suspect of being loanwords—and are not traceable to any other known language. There is little speculation as to the affinities of this substratum language, or these languages, and it is thus best treated as unclassified.[57] Other researchers disagree with the assumption of a single substratum language and argue that several languages are involved.[58] A related proposal by Gordon Whittaker[59] is that the language of the proto-literary texts from the Late Uruk period (c. 3350–3100 BC) is really an early Indo-European language which he terms "Euphratic".

In the Old Babylonian period and after it, the Sumerian used by scribes was influenced by their mother tongue, Akkadian, and sometimes more generally by imperfect acquisition of the language. As a result, various deviations from its original structure occur in texts or copies of texts from these times. The following effects have been found in the Old Babylonian period:[18]

For Middle Babylonian and later texts, additional deviations have been noted:[34]