Surface-mount technology

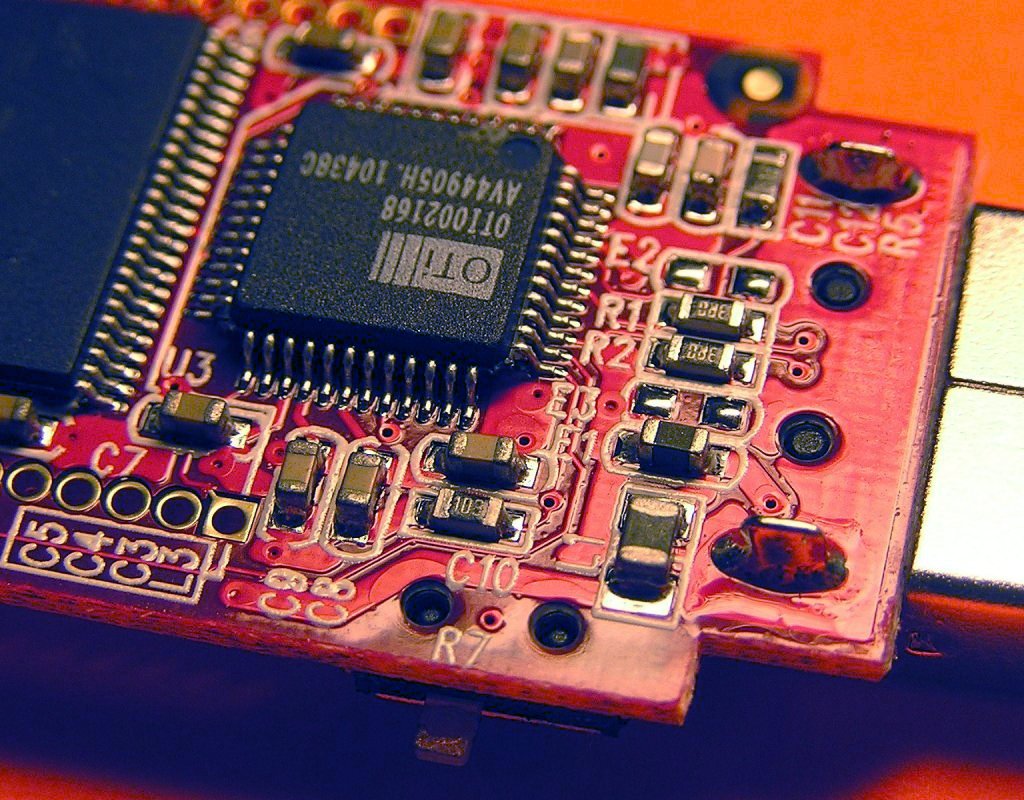

Surface-mount technology (SMT), originally called planar mounting,[1] is a method in which the electrical components are mounted directly onto the surface of a printed circuit board (PCB).[2] An electrical component mounted in this manner is referred to as a surface-mount device (SMD). In industry, this approach has largely replaced the through-hole technology construction method of fitting components, in large part because SMT allows for increased manufacturing automation which reduces cost and improves quality.[3] It also allows for more components to fit on a given area of substrate. Both technologies can be used on the same board, with the through-hole technology often used for components not suitable for surface mounting such as large transformers and heat-sinked power semiconductors.

An SMT component is usually smaller than its through-hole counterpart because it has either smaller leads or no leads at all. It may have short pins or leads of various styles, flat contacts, a matrix of solder balls (BGAs), or terminations on the body of the component.

History[edit]

Surface-mount technology was developed in the 1960s. By 1986 surface mounted components accounted for 10% of the market at most, but was rapidly gaining popularity.[4] By the late 1990s, the great majority of high-tech electronic printed circuit assemblies were dominated by surface mount devices. Much of the pioneering work in this technology was done by IBM. The design approach first demonstrated by IBM in 1960 in a small-scale computer was later applied in the Launch Vehicle Digital Computer used in the Instrument Unit that guided all Saturn IB and Saturn V vehicles.[5] Components were mechanically redesigned to have small metal tabs or end caps that could be directly soldered to the surface of the PCB. Components became much smaller and component placement on both sides of a board became far more common with surface mounting than through-hole mounting, allowing much higher circuit densities and smaller circuit boards and, in turn, machines or subassemblies containing the boards.

Often the surface tension of the solder is enough to hold the parts to the board; in rare cases parts on the bottom or "second" side of the board may be secured with a dot of adhesive to keep components from dropping off inside reflow ovens if the part is above the limit of 30g per square inch of pad area.[6] Adhesive is sometimes used to hold SMT components on the bottom side of a board if a wave soldering process is used to solder both SMT and through-hole components simultaneously. Alternatively, SMT and through-hole components can be soldered on the same side of a board without adhesive if the SMT parts are first reflow-soldered, then a selective solder mask is used to prevent the solder holding those parts in place from reflowing and the parts floating away during wave soldering. Surface mounting lends itself well to a high degree of automation, reducing labor cost and greatly increasing production rates.

Conversely, SMT does not lend itself well to manual or low-automation fabrication, which is more economical and faster for one-off prototyping and small-scale production, and this is one reason why many through-hole components are still manufactured. Some SMDs can be soldered with a temperature-controlled manual soldering iron, but unfortunately, those that are very small or have too fine a lead pitch are impossible to manually solder without expensive hot-air solder reflow equipment. SMDs can be one-quarter to one-tenth the size and weight, and one-half to one-quarter the cost of equivalent through-hole parts, but on the other hand, the costs of a certain SMT part and of an equivalent through-hole part may be quite similar, though rarely is the SMT part more expensive.