Syphilis

Syphilis (/ˈsɪfəlɪs/) is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum.[1] The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary).[1][2] The primary stage classically presents with a single chancre (a firm, painless, non-itchy skin ulceration usually between 1 cm and 2 cm in diameter) though there may be multiple sores.[2] In secondary syphilis, a diffuse rash occurs, which frequently involves the palms of the hands and soles of the feet.[2] There may also be sores in the mouth or vagina.[2] In latent syphilis, which can last for years, there are few or no symptoms.[2] In tertiary syphilis, there are gummas (soft, non-cancerous growths), neurological problems, or heart symptoms.[3] Syphilis has been known as "the great imitator" as it may cause symptoms similar to many other diseases.[2][3]

Not to be confused with Sisyphus.Syphilis

Firm, painless, non-itchy skin ulcer[1]

Treponema pallidum, usually spread by sex[1]

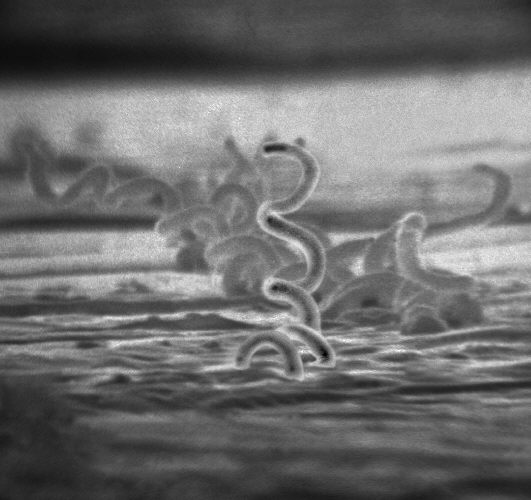

Blood tests, dark field microscopy of infected fluid[2][3]

Many other diseases[2]

45.4 million / 0.6% (2015, global)[5]

107,000 (2015, global)[6]

Syphilis is most commonly spread through sexual activity.[2] It may also be transmitted from mother to baby during pregnancy or at birth, resulting in congenital syphilis.[2][7] Other diseases caused by Treponema bacteria include yaws (T. pallidum subspecies pertenue), pinta (T. carateum), and nonvenereal endemic syphilis (T. pallidum subspecies endemicum).[3] These three diseases are not typically sexually transmitted.[8] Diagnosis is usually made by using blood tests; the bacteria can also be detected using dark field microscopy.[2] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.) recommend all pregnant women be tested.[2]

The risk of sexual transmission of syphilis can be reduced by using a latex or polyurethane condom.[2] Syphilis can be effectively treated with antibiotics.[4] The preferred antibiotic for most cases is benzathine benzylpenicillin injected into a muscle.[4] In those who have a severe penicillin allergy, doxycycline or tetracycline may be used.[4] In those with neurosyphilis, intravenous benzylpenicillin or ceftriaxone is recommended.[4] During treatment people may develop fever, headache, and muscle pains, a reaction known as Jarisch–Herxheimer.[4]

In 2015, about 45.4 million people had syphilis infections,[5] of which six million were new cases.[9] During 2015, it caused about 107,000 deaths, down from 202,000 in 1990.[6][10] After decreasing dramatically with the availability of penicillin in the 1940s, rates of infection have increased since the turn of the millennium in many countries, often in combination with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).[3][11] This is believed to be partly due to increased sexual activity, increased prostitution, and decreased use of condoms.[12][13][14]

Prevention

Vaccine

As of 2018, there is no vaccine effective for prevention.[33] Several vaccines based on treponemal proteins reduce lesion development in an animal model but research continues.[43][44]

Sex

Condom use reduces the likelihood of transmission during sex, but does not eliminate the risk.[45] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) states, "Correct and consistent use of latex condoms can reduce the risk of syphilis only when the infected area or site of potential exposure is protected.[46] However, a syphilis sore outside of the area covered by a latex condom can still allow transmission, so caution should be exercised even when using a condom."[47]

Abstinence from intimate physical contact with an infected person is effective at reducing the transmission of syphilis. The CDC states, "The surest way to avoid transmission of sexually transmitted diseases, including syphilis, is to abstain from sexual contact or to be in a long-term mutually monogamous relationship with a partner who has been tested and is known to be uninfected."[47]

Treatment

Historic use of mercury

As a form of chemotherapy, elemental mercury had been used to treat skin diseases in Europe as early as 1363.[63] As syphilis spread, preparations of mercury were among the first medicines used to combat it. Mercury is in fact highly anti-microbial: by the 16th century it was sometimes found to be sufficient to halt development of the disease when applied to ulcers as an inunction or when inhaled as a suffumigation. It was also treated by ingestion of mercury compounds.[64] Once the disease had gained a strong foothold, however, the amounts and forms of mercury necessary to control its development exceeded the human body's ability to tolerate it, and the treatment became worse and more lethal than the disease. Nevertheless, medically directed mercury poisoning became widespread through the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries in Europe, North America, and India.[65] Mercury salts such as mercury (II) chloride were still in prominent medical use as late as 1916, and considered effective and worthwhile treatments.[66]

Early infections

The first-line treatment for uncomplicated syphilis (primary or secondary stages) remains a single dose of intramuscular benzathine benzylpenicillin.[67] The bacterium is highly vulnerable to penicillin when treated early, and a treated individual is typically rendered non-infective in about 24 hours.[68] Doxycycline and tetracycline are alternative choices for those allergic to penicillin; due to the risk of birth defects, these are not recommended for pregnant women.[67] Resistance to macrolides, rifampicin, and clindamycin is often present.[33] Ceftriaxone, a third-generation cephalosporin antibiotic, may be as effective as penicillin-based treatment.[3] It is recommended that a treated person avoid sex until the sores are healed.[37] In comparison to azithromycin for treatment in early infection, there is lack of strong evidence for superiority of azithromycin to benzathine penicillin G.[69]

Late infections

For neurosyphilis, due to the poor penetration of benzathine penicillin into the central nervous system, those affected are given large doses of intravenous penicillin G for a minimum of 10 days.[3][33] If a person is allergic to penicillin, ceftriaxone may be used or penicillin desensitization attempted.[3] Other late presentations may be treated with once-weekly intramuscular benzathine penicillin for three weeks.[3] Treatment at this stage solely limits further progression of the disease and has a limited effect on damage which has already occurred.[3] Serologic cure can be measured when the non-treponemal titers decline by a factor of 4 or more in 6–12 months in early syphilis or 12–24 months in late syphilis.[20]