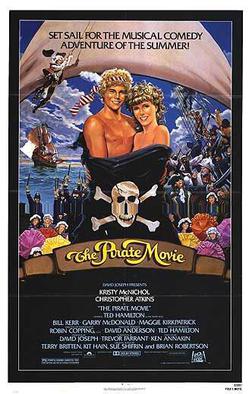

The Pirate Movie

The Pirate Movie is a 1982 Australian musical romantic comedy film directed by Ken Annakin, and starring Christopher Atkins and Kristy McNichol. Loosely based on Gilbert and Sullivan's 1879 comic opera The Pirates of Penzance, the original music score is composed by Mike Brady and Peter Sullivan (no relation to Pirates of Penzance composer Arthur Sullivan).

"Pirate movie" redirects here. For the genre, see pirate film. For copyright infringement, see film piracy.The film performed far below expectations in initial release and is generally reviewed very poorly,[4][5] but fared far more positively with audiences.[6] It has developed a cult following[7] following home media release and TV airings.

Plot[edit]

Mabel Stanley is an introverted and bookish teenage girl from the United States in a seaside community in Australia as an exchange student. She attends a local pirate festival featuring a swordplay demonstration led by a young curly-haired instructor and fellow American, who then invites her for a ride on his boat. She is duped by her exchange family sisters, Edith, Kate and Isabel, into missing the launch, so she rents a small sailboat to give chase. A sudden storm throws her overboard, and she washes up on a beach.

She subsequently dreams an adventure that takes place a century before. In this fantasy sequence, the swordplay instructor is now named Frederic, a young apprentice of the Pirates of Penzance, celebrating his 21st birthday on a pirate vessel. Frederic refuses an invitation from the Pirate King, his adoptive father, to become a full pirate, as his birth parents were murdered by their contemporaries. Frederic swears to avenge their deaths and is forced off of the ship on a small boat.

Adrift, Frederic spies Mabel and her older sisters on a nearby island and swims to shore to greet them. In a reversal of roles, Mabel is a confident, assertive, and courageous young woman, while her sisters are prim, proper and conservative. Frederic quickly falls for Mabel and proposes marriage, but local custom requires the elder sisters to marry first.

Soon, Frederic's old mates come ashore, also looking for women and kidnap Mabel's sisters. Major-General Stanley, Mabel's father, arrives and convinces the Pirate King to free his daughters and leave in peace. The pirates anchor their ship just outside the harbour instead of actually leaving. Mabel wants Frederic to gain favour with her father so they can marry, so she plots to recover the family treasure stolen years earlier by the pirates. Unfortunately, the treasure was lost at sea, but the location where it lies was tattooed as a map on the Pirate King's back. Mabel successfully tricks the Pirate King into revealing his tattoo while Frederic sketches a copy. After Mabel manages to escape from him, she and Frederic, who has sabotaged the pirate's ship, leap overboard and swim for safety. The pirates open fire on them, but the ship partially sinks, enabling them to escape.

The next day, Mabel and Frederic recover the stolen treasure and present it to her father. The Major-General is underwhelmed as he believes the treasure will simply be stolen again once the pirates realise it is missing. Mabel dispatches Frederic to raise an army for protection, but the Pirate King interferes. The ship nurse, Ruth, convinces them to stop fighting, reminding the Pirate King of Frederic's apprenticeship contract. Frederic's birthday is 29 February, and he is dismayed to see that the contract specifies his twenty-first birthday, rather than his twenty-first year. As his birthday occurs every four years, Frederic has celebrated only five birthdays and is still bound by contract to remain with the pirates.

That night, the pirates raid the Stanley estate, and the Pirate King orders their execution. Mabel demands a "happy ending" – admitting for the first time that she believes this all to be a dream. Everyone – even the pirates – cheers their approval, leaving the Pirate King disappointed and shocked. Mabel then confronts her father, but the Major-General is steadfast that the marriage custom remains in effect. Mabel quickly pairs each of her older sisters with a pirate, and she also pairs the Pirate King to Ruth. With Mabel and Frederic now free to marry, the fantasy sequence ends in song and dance.

Mabel wakes up back on the beach to discover that she is wearing the wedding ring that Frederic had given her in her dream. At that moment, the handsome swordplay instructor arrives and lifts her to her feet. He passionately kisses Mabel, who is still shaken by her dream. She asks if his name is Frederic. He assures her that he isn't who she imagines him to be, but then carries her off to marry her, thus giving Mabel her happy ending in reality as well.

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

Joseph Papp's Broadway revival of "The Pirates of Penzance" had piqued the interest of music executive David Joseph, who had recently entered into a production partnership with actor Ted Hamilton (The Pirate King).[8] Together, they hatched the idea for a comedic film adaptation. Initially, Papp was approached to direct, but he declined because he had his own plans for a film adaptation of the musical.[9]

The producers then turned to 20th Century Fox studio, which not only agreed to distribute the film but also provided two lead actors for the project. Kristy McNichol, renowned for her role in the TV drama Family, had transitioned to a film career and was eager for another big-screen opportunity. Christopher Atkins, who had made a splash in The Blue Lagoon, was a notable presence in teen magazines. Both actors were invited to watch a production of "Penzance" in preparation for their roles. McNichol said that she was bored by it,[10] and Atkins believed he was cast primarily due to his resemblance to his Broadway counterpart, Rex Smith.[11] Atkins was under contract to Columbia Pictures, which lent him out to Fox for the movie, and then took half of his profits.[12] Although McNichol had sung professionally and released an album with her brother, she went to a vocal coach to prepare.[13] Meanwhile, Atkins, who had no musical experience,[14] not only had to be taught to sing, but underwent extensive dancing and fencing training.[15]

As the production gathered momentum, Ted Hamilton enlisted Trevor Farrant,[16] a collaborator from previous projects, to craft the screenplay.[17] Farrant received a substantial payment of $55,000 for his work, which, when adjusted for inflation, equates to $174,000. This was reported to be the highest salary ever earned by an Australian screenwriter at the time.[18] Farrant claimed to have completed the screenplay in just four days.[19]

Originally, the production had selected the young director Richard Franklin to helm the film.[20] Rehearsals commenced in August 1981, with plans to begin shooting in September.[21] Excitement was palpable among the cast and crew as they embarked on rehearsals.[22] However, McNichol, who had final script approval, clashed with Franklin over his vision for the film, resulting in Franklin's sudden departure from the production.[23] Ted Hamilton had the unenviable task of informing the cast and crew that "creative differences" had forced Franklin to exit.[24] This unexpected turn of events left production in a state of uncertainty, forcing Atkins (and presumably McNichol) to return to the United States[25] while the Australian team continued rehearsals.[26]

Ultimately, Ken Annakin was hired as Franklin's replacement. Being more than twice the age of his predecessor, there were concerns within the cast about Annakin's suitability for the role,[27] but production soldiered on.

Filming[edit]

With the new director in place, principal photography began in November 1981[28] and stretched into January 1982.

Since McNichol wore a light, natural makeup, none of the "sisters" were allowed to enhance their features with makeup. Two actresses arrived with eyeliner on, were reprimanded and forced to remove it.[29]

Annakin found himself at odds with McNichol over one annoyance: her chewing gum. She continuously had gum in her mouth, and frequently tried to hide it in her cheek.[30] This led to an outtake that's seen right before the credits roll, which seems fairly random out of context.

Primary locations included the Polly Woodside at the South Melbourne wharf, the Farm and Mansion at Werribee Park, and the Loch Ard on the Great Ocean Road, Port Campbell, from November 1981 to January 1982. Secondary locations included various parts of Sydney, namely McDonald's Cremorne (in the beginning sequences, after Fred invites Mabel and her friends on the boat), Rushcutters Bay Marina (where Mabel obtains a small sailboat), and Palm Beach for some of the beach scenes. The Stanley family's library, which required a controlled environment for all of the stunt work, was a set erected in a Sydney studio.[31]

Post-production[edit]

The film that was released was a little bit different from the film that was shot. "Pumping and Blowin'" was originally supposed to include a sequence with Mabel's sisters frolicking underwater,[32] but this footage was scrapped and replaced with animation by Yellow Submarine veteran Maggie Geddes.[33]

Despite Hamilton's objections, Fox ended up shaving 20 minutes out of the movie, which he claimed had "emasculated" the film and ruined a lot of the jokes.[34] They were particularly sensitive to racial jokes,[35] but other off-colour humor found its way onto the cutting room floor.[36]

The Pirate Movie: The Original Soundtrack from the Motion Picture

Release[edit]

Promotion[edit]

In preparation for the film's August release, 20th Century Fox embarked on an extensive $3 million promotional campaign.[49] It was one of the earliest movies to feature an electronic press kit distributed on videocassette.[50]

Just prior to the film's August debut, Baskin-Robbins released "Pirates' Gold" as their flavour of the month for July.[51] This ice cream flavour was rum-flavoured and included butter brickle candy pieces, accompanied by playful marketing featuring a pirate-themed caricature of Bill Kerr, who is seen selling the ice cream from a Baskin-Robbins cart at the beginning of the movie.[52]

A total of 179 American shopping malls joined in on the promotional extravaganza.[53] The campaign encompassed various engaging activities such as colouring contests featuring poster artwork,[54] costume contests,[55][56] treasure hunts,[57] fashion shows,[58][59] and giveaways.[60] Freebie items included pirate banners, movie posters, chocolate "gold coin" candy, videotapes, and movie tickets.[61] Fox also arranged radio giveaways of sailboards, and Hang Ten gave away exclusive posters.[61]

Christopher Atkins and Kristy McNichol did the obligatory rounds with journalists and tabloid-news reporters. On television, Atkins took the spotlight as he hosted "The Swashbucklers," a syndicated TV special that delved into the history of pirate films. The show included an appearance by McNichol and provided behind-the-scenes glimpses into the making of the movie.[62][63][64] Atkins also showcased his newfound musical talents by performing "How Can I Live Without Her?" on popular shows like American Bandstand,[65] Solid Gold,[66] and the Australian series Countdown,[67] which he even guest-hosted. He also appeared at record store signings to promote the soundtrack.[68] Additionally, the cast version of "Happy Ending" closed ABC's Thanksgiving TV special "Dancin' on Air."[69]

The Peter Cupples Band released a music video for their rendition of "Happy Ending"[70] and also appeared on Countdown. Their performance took a dramatic turn as Atkins burst onto the stage, engaging in a mock duel with a pirate.[71]

An additional bit of promotion was ill-timed. The same month that the movie was released, Atkins graced the cover of Playgirl magazine.[72] Although there were no full-frontal images included in that spread,[73] it was an era when male nudity was very taboo,[74] creating a disconnect with the family audience that Fox was targeting for the film's marketing.

Box office[edit]

In the USA, the film opened at #5, trailing behind juggernaut E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, Things Are Tough All Over, and An Officer and a Gentleman.[5] In its second week, after the reviews hit and now in direct competition with a successful re-release of Fox's own Star Wars, it plummeted to #13,[75] and dropped off the charts in its third week. Ultimately, the film grossed $7,983,086 in its American theatrical release.[76]

The film earned A$1,013,000 at the Australian box office.[77][78]

Critical reception[edit]

Fox didn't allow the press to pre-screen the film, with executive Vice-President Irv Ivers explaining, "You can look at movies and you can tell if they're going to be killed by critics."[79] He then asked the reporter, "If you were in my place, would you show them?" Just as Ivers foresaw, when the reviews finally surfaced, "The Pirate Movie" was brutally criticized, with numerous headlines invoking pirate-themed puns, including piracy,[80][81] shipwrecks,[82] walking the plank,[83][84][85][86][87] and other stereotypical terminology.

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 9% based on 11 reviews, with an average rating of 2.23/10.[6] On Metacritic, it has a weighted average score of 19 out of 100, based on reviews from 6 critics, indicating "Overwhelming dislike".[88]

Screenwriter Trevor Farrant issued a press statement after the American reviews surfaced but before the Australian release. Farrant blamed "everybody" else for the film's box-office failure,[89] decrying "phallic and homosexual jokes which I didn't write,"[90] and denouncing product placement for McDonald's and Baskin-Robbins, asserting, "This is not a film, this is prostitution. The final film is a travesty of my script."[91] Producer and star Ted Hamilton countered Farrant's claims by suggesting that he was "acting irrationally."[92]

Michelene Keating of The Tucson Citizen was bewildered by the audience's reaction, noting, "Everyone who attended the same matinee showing that I did (a sparse attendance and, to my surprise, mostly adults) did not share my opinion of the movie. A woman who sat in front of me laughed quite a bit between going out three times for popcorn refills."[93] The Sunday Pennsylvanian's Mary Lou Kelsey was surrounded by a young crowd that made her "feel like you need a walker," and complained that the audience was "laughing hysterically at the most infantile jokes you have ever heard. You might need a walker, but their brains need corrective surgery."[94]

Among the few positive reviews, Martha Steimel of The Witchita Falls Records News gushed that it was a "wonderfully funny," "rollicking frolic,"[95] remarking that "the fun of the pirate movie is that we know all along it's a dream." The Orlando Sentinel's Sumner Rand called it "a lighthearted, colorful summertime romp," concluding, "Unless you're a Gilbert & Sullivan purist, you should be entertained."[96] Bill Pelletier of The Evansville Press warned that "a trip to the concession stand could rob you of some funny moments," and concluded, "The key to this Australian-made beauties, me hardies, is fun, fun, fun!"[97] The Louisville Courier Journal's Owen Hardy remarked that "despite its problems, 'The Pirate Movie' at times displays an infectious inanity," and that "the cast sings with gusto."[98]

The Irish Times review called The Pirate Movie a "travesty" of the Gilbert and Sullivan original and said "with a philosophy of shove everything in regardless, it's nothing more than a waste of Miss McNichol's abilities, the audience's time and the incentives offered to make films in Australia."[99] Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide rated the film as a BOMB and stated: "Not only trashes the original, but also fails on its own paltry terms. It should have been called The Rip-off Movie".[100] TV Guide stated "Pop tunes are mixed in with some of the original G&S songs in a pirate period setting that grates on the nerves, as does the inane toilet humor that substitutes for wit. All the performers, especially McNichol, look as if they can't wait until the film is over, and one can hardly blame them."[101]

Michael and Harry Medved's book Son of Golden Turkey Awards includes The Pirate Movie's "First Love" on its list of "Worst Rock 'N Roll Lyrics in a Movie".[102] The most creative review came from the Argus Leader's Marshall Fine, who set his poetic opus to the rhythm of "The Major-General's Song," ultimately stating, "In short, 'The Pirate Movie' should crawl back into the sewer. At least that's the opinion of this modern film reviewer."[103]

Australian film critic Michael Adams later included The Pirate Movie on his list of the worst ever Australian films, along with Phantom Gold, The Glenrowan Affair, Houseboat Horror, Welcome to Woop Woop, Les Patterson Saves the World and Pandemonium.[104]