The Wizard of Oz

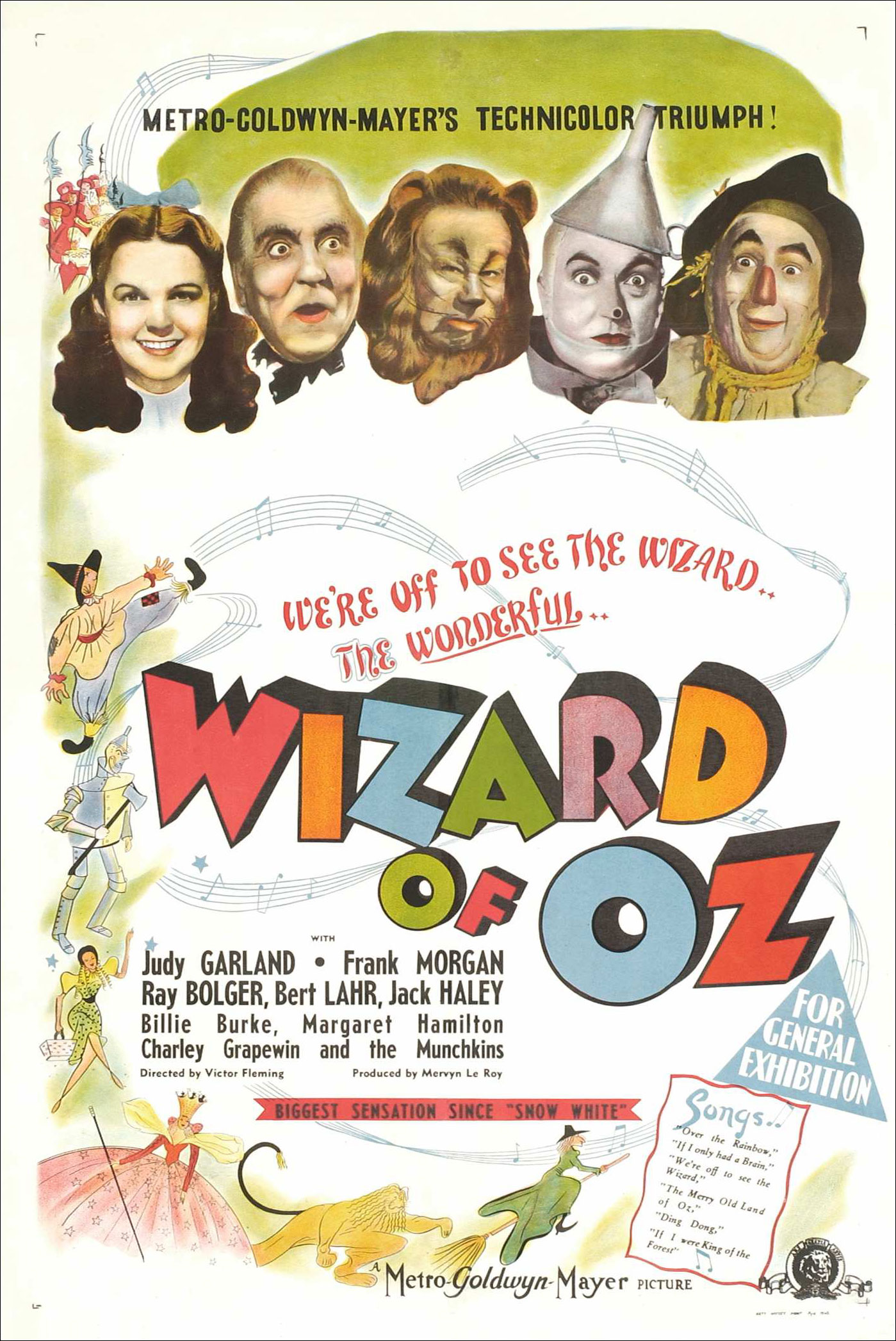

The Wizard of Oz is a 1939 American musical fantasy film produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM). An adaptation of L. Frank Baum's 1900 children's fantasy novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, it was primarily directed by Victor Fleming, who left production to take over the troubled Gone with the Wind. It stars Judy Garland, Frank Morgan, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, Jack Haley, Billie Burke and Margaret Hamilton. Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson and Edgar Allan Woolf received credit for the screenplay, while others made uncredited contributions. The music was composed by Harold Arlen and adapted by Herbert Stothart, with lyrics by Edgar "Yip" Harburg.

This article is about the 1939 film. For the book, see The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. For other uses, see The Wizard of Oz (disambiguation).The Wizard of Oz

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900 children's novel)

by L. Frank Baum

- August 10, 1939 (Green Bay)

- August 25, 1939 (United States)

101 minutes[2]

United States

English

$29.7 million

The Wizard of Oz is celebrated for its use of Technicolor, fantasy storytelling, musical score, and memorable characters. It was a critical success and was nominated for five Academy Awards, including Best Picture, winning Best Original Song for "Over the Rainbow" and Best Original Score for Stothart; an Academy Juvenile Award was presented to Judy Garland. While the film was sufficiently popular at the box office, it failed to make a profit for MGM until its 1949 re-release, earning only $3 million on a $2.7 million budget, making it MGM's most expensive production at the time.[3][5][6]

The 1956 television broadcast premiere of the film on CBS reintroduced the film to the public. According to the U.S. Library of Congress, it is the most seen film in movie history.[7][8] In 1989, it was selected by the Library of Congress as one of the first 25 films for preservation in the United States National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant";[9][10] it is also one of the few films on UNESCO's Memory of the World Register.[11] The film was ranked second in Variety's inaugural 100 Greatest Movies of All Time list published in 2022.[12] It was among the top ten in the 2005 BFI (British Film Institute) list of "50 films to be seen by the age of 14" and is on the BFI's updated list of "50 films to be seen by the age of 15" released in May 2020.[13] The Wizard of Oz has become the source of many quotes referenced in contemporary popular culture. The film frequently ranks on critics' lists of the greatest films of all time and is the most commercially successful adaptation of Baum's work.[7][14]

Uncredited

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

Production on the film began when Walt Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) showed that films adapted from popular children's stories and fairytales could be successful.[18][19] In January 1938, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer bought the rights to L. Frank Baum's popular novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz from Samuel Goldwyn. Goldwyn had considered making the film as a vehicle for Eddie Cantor, who was under contract to Samuel Goldwyn Productions and whom Goldwyn wanted to cast as the Scarecrow.[19]

The script went through several writers and revisions.[20] Mervyn LeRoy's assistant, William H. Cannon, had submitted a brief four-page outline.[20] Because recent fantasy films had not fared well, he recommended toning down or removing the magical elements. In his outline, the Scarecrow was a man so stupid that the only employment open to him was scaring crows from cornfields, and the Tin Woodman was a criminal so heartless that he was sentenced to be placed in a tin suit for eternity. This torture softened him into somebody gentler and kinder.[20] Cannon's vision was similar to Larry Semon's 1925 film adaptation, in which the magical elements are absent.

Afterward, LeRoy hired screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz, who delivered a 17-page draft of the Kansas scenes. A few weeks later, Mankiewicz delivered a further 56 pages. LeRoy also hired Noel Langley and poet Ogden Nash to write separate versions of the story. None of these three knew about the others, and this was not an uncommon procedure. Nash delivered a four-page outline; Langley turned in a 43-page treatment and a full film script. Langley then turned in three more scripts, this time incorporating the songs written by Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg. Florence Ryerson and Edgar Allan Woolf submitted a script and were brought on board to touch up the writing. They were asked to ensure that the story stayed true to Baum's book. However, producer Arthur Freed was unhappy with their work and reassigned it to Langley.[21] During filming, Victor Fleming and John Lee Mahin revised the script further, adding and cutting some scenes. Haley and Lahr are also known to have written some of their dialogue for the Kansas sequence.

They completed the final draft of the script on October 8, 1938, following numerous rewrites.[22] Others who contributed to the adaptation without credit include Irving Brecher, Herbert Fields, Arthur Freed, Yip Harburg, Samuel Hoffenstein, Jack Mintz, Sid Silvers, Richard Thorpe, George Cukor and King Vidor. Only Langley, Ryerson, and Woolf were credited for the script.[19]

In addition, songwriter Harburg's son (and biographer) Ernie Harburg reported:

Special effects, makeup and costumes[edit]

Arnold Gillespie, the film's special effects director, employed several techniques.[33] Developing the tornado scene was especially costly. Gillespie used muslin cloth to make the tornado flexible, after a previous attempt with rubber failed. He hung the 35 ft (11 m) of muslin from a steel gantry and connected the bottom to a rod. By moving the gantry and rod, he was able to create the illusion of a tornado moving across the stage. Fuller's earth was sprayed from both the top and bottom using compressed air hoses to complete the effect. Dorothy's house was recreated using a model.[51] Stock footage of this tornado was later recycled for a climactic scene in the 1943 musical film Cabin in the Sky, directed by Judy Garland's eventual second husband Vincente Minnelli.[52]

The Cowardly Lion and Scarecrow masks were made of foam latex makeup created by makeup artist Jack Dawn. Dawn was one of the first to use this technique.[53][54] It took an hour each day to slowly peel Bolger's glued-on mask from his face, a process that eventually left permanent lines around his mouth and chin.[40][55]

The Tin Man's costume was made of leather-covered buckram, and the oil used to grease his joints was made from chocolate syrup.[56] The Cowardly Lion's costume was made from real lion skin and fur.[57] Due to the heavy makeup, Bert Lahr could only consume soup and milkshakes on break, which eventually made him sick. After a few months, Lahr put his foot down and requested normal meals along with makeup redos after lunch.[58][59] For the "horse of a different color" scene, Jell-O powder was used to color the white horses.[60] Asbestos was used to achieve some of the special effects, such as the witch's burning broomstick and the fake snow that covers Dorothy as she sleeps in the field of poppies.[61][62]

Post-production[edit]

Principal photography concluded with the Kansas sequences on March 16, 1939. Reshoots and pickup shots were done through April and May and into June, under the direction of producer LeRoy. When the "Over the Rainbow" reprise was removed after subsequent test screenings in early June, Garland had to be brought back to reshoot the "Auntie Em, I'm frightened!" scene without the song. The footage of Blandick's Aunt Em, as shot by Vidor, had already been set aside for rear-projection work, and was reused.

After Hamilton's torturous experience with the Munchkinland elevator, she refused to do the pickups for the scene where she flies on a broomstick that billows smoke, so LeRoy had stunt double Betty Danko perform instead. Danko was severely injured when the smoke mechanism malfunctioned.[67]

At this point, the film began a long, arduous post-production. Herbert Stothart composed the film's background score, while A. Arnold Gillespie perfected the special effects, including many of the rear-projection shots. The MGM art department created matte paintings for many scene backgrounds.

A significant innovation planned for the film was the use of stencil printing for the transition to Technicolor. Each frame was to be hand-tinted to maintain the sepia tone. However, it was abandoned because it was too expensive and labor-intensive, and MGM used a simpler, less expensive technique: During the May reshoots, the inside of the farmhouse was painted sepia, and when Dorothy opens the door, it is not Garland, but her stand-in, Bobbie Koshay, wearing a sepia gingham dress, who then backs out of frame. Once the camera moves through the door, Garland steps back into frame in her bright blue gingham dress (as noted in DVD extras), and the sepia-painted door briefly tints her with the same color before she emerges from the house's shadow, into the bright glare of the Technicolor lighting. This also meant that the reshoots provided the first proper shot of Munchkinland. If one looks carefully, the brief cut to Dorothy looking around outside the house bisects a single long shot, from the inside of the doorway to the pan-around that finally ends in a reverse-angle as the ruins of the house are seen behind Dorothy and she comes to a stop at the foot of the small bridge.

Test screenings of the film began on June 5, 1939.[68] Oz initially ran nearly two hours long. In 1939, the average film ran for about 90 minutes. LeRoy and Fleming knew they needed to cut at least 15 minutes to get the film down to a manageable running time. Three sneak previews in San Bernardino, Pomona and San Luis Obispo, California, guided LeRoy and Fleming in the cutting. Among the many cuts were "The Jitterbug" number, the Scarecrow's elaborate dance sequence following "If I Only Had a Brain", reprises of "Over the Rainbow" and "Ding-Dong! The Witch Is Dead", and a number of smaller dialogue sequences. This left the final, mostly serious portion of the film with no songs, only the dramatic underscoring.

"Over the Rainbow" was almost deleted. MGM felt that it made the Kansas sequence too long, as well as being far over the heads of the target audience of children. The studio also thought that it was degrading for Garland to sing in a barnyard. LeRoy, uncredited associate producer Arthur Freed and director Fleming fought to keep it in, and they eventually won. The song went on to win the Academy Award for Best Original Song, and came to be identified so strongly with Garland herself that she made it her signature song.

After the preview in San Luis Obispo in early July, the film was officially released in August 1939 at its current 101-minute running time.

Reception[edit]

Critical response[edit]

The Wizard of Oz received widespread acclaim upon its release. Writing for The New York Times, Frank Nugent considered the film a "delightful piece of wonder-working which had the youngsters' eyes shining and brought a quietly amused gleam to the wiser ones of the oldsters. Not since Disney's Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs has anything quite so fantastic succeeded half so well."[101] Nugent had issues with some of the film's special effects:

Notes

Bibliography

Further reading