Treaty of Paris (1763)

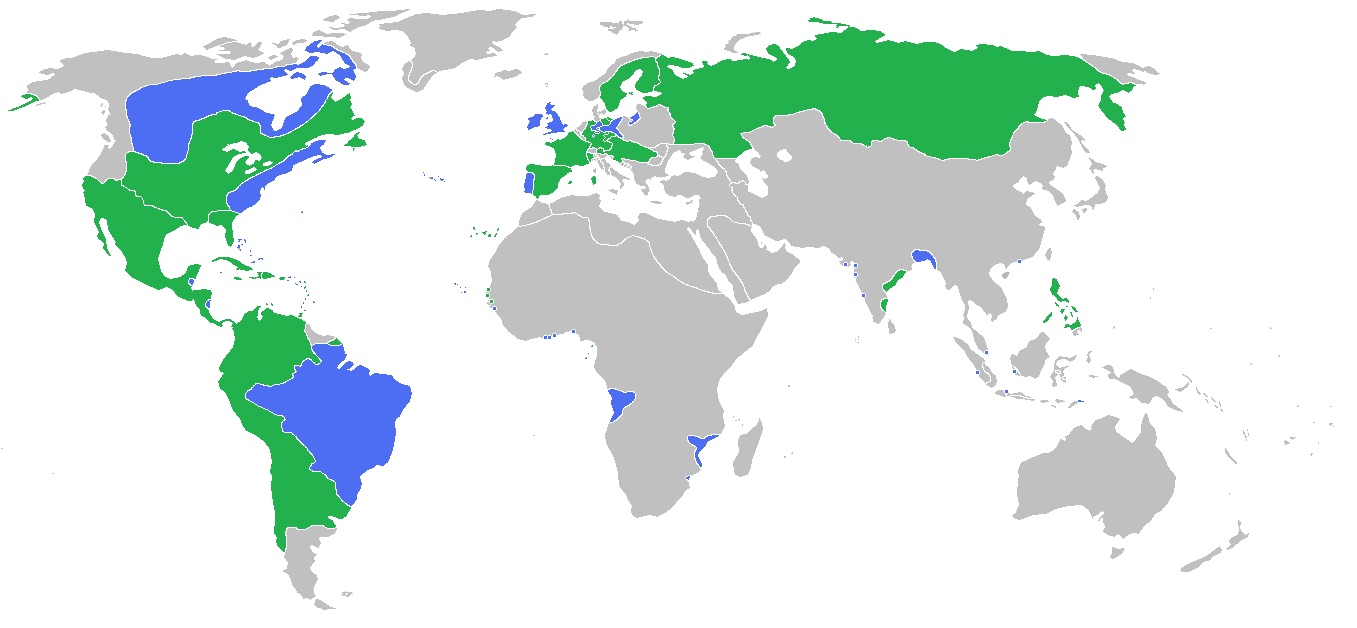

The Treaty of Paris, also known as the Treaty of 1763, was signed on 10 February 1763 by the kingdoms of Great Britain, France and Spain, with Portugal in agreement, following Great Britain and Prussia's victory over France and Spain during the Seven Years' War.

Not to be confused with Treaty of Paris (1783), the treaty that ended the American Revolution.Context

End of the Seven Years' War (known as the French and Indian War in the United States)

10 February 1763[1]

The signing of the treaty formally ended the conflict between France and Great Britain over control of North America (the Seven Years' War, known as the French and Indian War in the United States),[2] and marked the beginning of an era of British dominance outside Europe.[3] Great Britain and France each returned much of the territory that they had captured during the war, but Great Britain gained much of France's possessions in North America. Additionally, Great Britain agreed to protect Roman Catholicism in the New World. The treaty did not involve Prussia and Austria, as they signed a separate agreement, the Treaty of Hubertusburg, five days later.

Canada question[edit]

British perspective[edit]

The war was fought all over the world, but the British began the war over French possessions in North America.[14] After a long debate of the relative merits of Guadeloupe, which produced £6 million a year in sugar, and Canada, which was expensive to keep, Great Britain decided to keep Canada for strategic reasons and to return Guadeloupe to France.[15] The war had weakened France, but it was still a European power. British Prime Minister Lord Bute wanted a peace that would not push France towards a second war.[16]

Although the Protestant British worried about having so many Roman Catholic subjects, Great Britain did not want to antagonize France by expulsion or forced conversion or for French settlers to leave Canada to strengthen other French settlements in North America.[17]

French perspective[edit]

Unlike Lord Bute, the French Foreign Minister, the Duke of Choiseul, expected a return to war. However, France needed peace to rebuild.[18] France preferred to keep its Caribbean possessions with their profitable sugar trade, rather than the vast Canadian lands, which had been a financial burden on France.[19] French diplomats believed that without France to keep the Americans in check, the colonists might attempt to revolt.[20] In Canada, France wanted open emigration for those, such as the nobility, who would not swear allegiance to the British Crown.[21] Finally, France required protection for Roman Catholics in North America.

Article IV stated:[13]

Dunkirk question[edit]

During the negotiations that led to the treaty, a major issue of dispute between Britain and France had been over the status of the fortifications of the French coastal settlement of Dunkirk. The British had long feared that it would be used as a staging post to launch a French invasion of Britain. Under the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, the British forced France to concede extreme limits on those fortifications. The 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle had allowed more generous terms,[22] and France constructed more significant defences for the town.

The 1763 treaty had Britain force France to accept the 1713 conditions and demolish the fortifications constructed since then.[23] That would be a continuing source of resentment to France, which would eventually have that provision overturned in the 1783 Treaty of Paris, which brought an end to the American Revolutionary War.