Treaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas,[a] signed in Tordesillas, Spain, on 7 June 1494, and ratified in Setúbal, Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Kingdom of Portugal and the Crown of Castile, along a meridian 370 leagues[b] west of the Cape Verde islands, off the west coast of Africa. That line of demarcation was about halfway between Cape Verde (already Portuguese) and the islands visited by Christopher Columbus on his first voyage (claimed for Castile and León), named in the treaty as Cipangu and Antillia (Cuba and Hispaniola).

This article is about the 1494 treaty between Portugal and Spain that divided the world as then understood between the two. For the treaty signed in 1524 between Spain and Monaco, see Treaty of Tordesillas (1524).Treaty of Tordesillas

7 June 1494 in Tordesillas, Spain

2 July 1494 in Spain

5 September 1494 in Portugal

24 January 1505 or 1506 by Pope Julius II[1][2]

To resolve the conflict that arose from the 1481 papal bull Aeterni regis which affirmed Portuguese claims to all non-Christian lands south of the Canary Islands after Columbus claimed the Antilles for Castile, and to divide trading and colonising rights for all lands located west of the Canary Islands between Portugal and Castile (later applied between the Spanish Crown and Portugal) to the exclusion of any other Christian empires.

The lands to the east would belong to Portugal and the lands to the west to Castile, modifying an earlier bull by Pope Alexander VI. The treaty was signed by Spain on 2 July 1494, and by Portugal on 5 September 1494. The other side of the world was divided a few decades later by the Treaty of Zaragoza, signed on 22 April 1529, which specified the antimeridian to the line of demarcation specified in the Treaty of Tordesillas. Portugal and Spain largely respected the treaties, while the indigenous peoples of the Americas did not acknowledge them.[9]

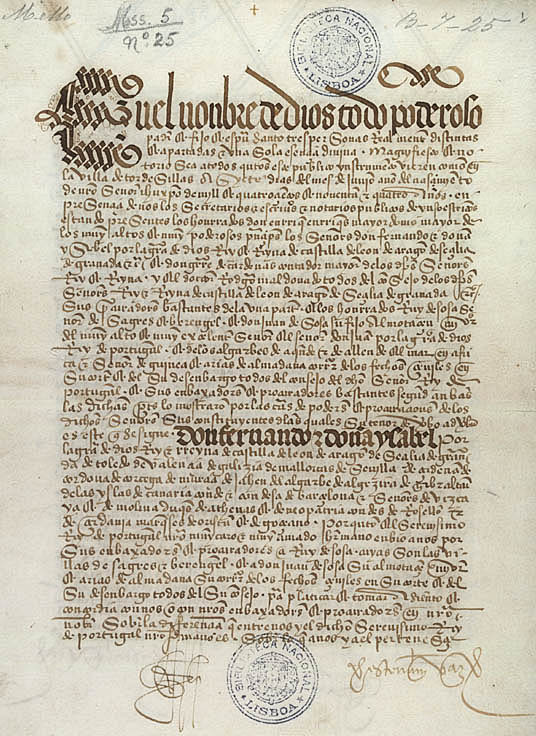

The treaty was included by UNESCO in 2007 in its Memory of the World Programme. Originals of both treaties are kept at the General Archive of the Indies in Spain and at the Torre do Tombo National Archive in Portugal.[10]

The Treaty of Tordesillas only specified the line of demarcation in leagues from the Cape Verde Islands. It did not specify the length of the league, its equivalent in equatorial degrees, or which of the Cape Verde islands was intended. Instead, the treaty provided that these matters were to be settled by a joint voyage. This voyage never occurred, and instead there were only a series of nonbinding expert opinions produced over the next several decades. Their computations were further complicated by remaining uncertainty about the exact equatorial circumference of the earth. As such, each proposed line can be variously computed using geographical leagues defined in terms of a degree using a ratio which applies regardless of the size of the earth or using a specifically measured league applied to the actual equatorial circumference of the earth, with allowances necessary for the imperfect Portuguese and Spanish knowledge of its true dimensions.[22]

Effect on other European powers[edit]

The attitude towards the treaty that other governments had was expressed by France's Francis I, who declared, "The sun shines for me as it does for others. I would very much like to see the clause of Adam's will by which I should be denied my share of the world."[47]