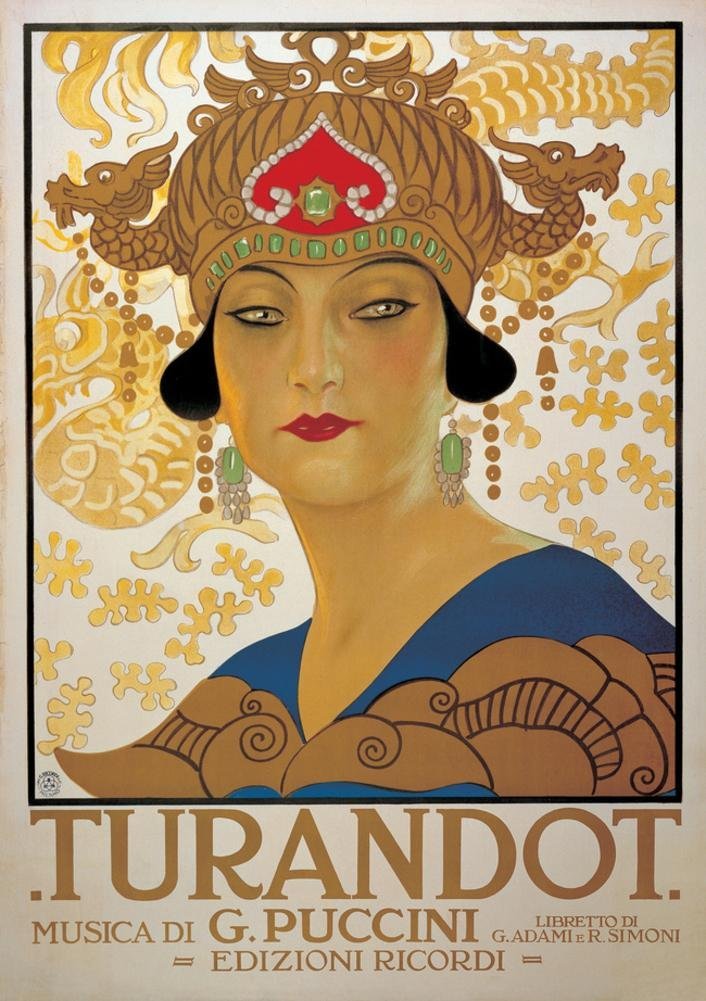

Turandot

Turandot (Italian: [turanˈdɔt] ⓘ;[1][2] see below) is an opera in three acts by Giacomo Puccini to a libretto in Italian by Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni. Puccini left the opera unfinished at the time of his death in 1924; it premiered in 1926 after the music was posthumously completed by Franco Alfano.

For other uses, see Turandot (disambiguation).Turandot

The opera is set in China and follows the Prince Calaf, who falls in love with the cold Princess Turandot.[3] In order to win her hand in marriage, a suitor must solve three riddles, with a wrong answer resulting in his execution. Calaf passes the test, but Turandot refuses to marry him. He offers her a way out: if she is able to guess his name before dawn the next day, he will accept death.

Origin and pronunciation of the name[edit]

The title of the opera is derived from the Persian term Turandokht (توراندخت, 'daughter of Turan'), a name frequently given to Central Asian princesses in Persian poetry. Turan is a region of Central Asia that was once part of the Persian Empire. Dokht is a contraction of dokhtar (daughter); the kh and t are both pronounced.[4]

Standard Italian pronunciation prescribes pronouncing the final t. However, according to Puccini scholar Patrick Vincent Casali, the t is silent in the name of the opera and of its title character, thus [turanˈdo]. Soprano Rosa Raisa, who created the title role, said that neither Puccini nor Arturo Toscanini, who conducted the first performances, ever pronounced the final t.[5] Similarly, prominent Turandot Eva Turner did not pronounce the final t in television interviews. Casali maintains that the musical setting of many of Calaf's utterances of the name makes sounding the final t all but impossible.[6] On the other hand, Simonetta Puccini, the composer's granddaughter and keeper of the Villa Puccini and Mausoleum, has said that the final t must be pronounced.[7]

Critical response[edit]

While long recognised as the most tonally adventurous of Puccini's operas,[52] Turandot has also been considered a flawed masterpiece, and some critics have been hostile. Joseph Kerman states that "Nobody would deny that dramatic potential can be found in this tale. Puccini, however, did not find it; his music does nothing to rationalize the legend or illuminate the characters."[53] Kerman also wrote that while Turandot is more "suave" musically than Puccini's earlier opera, Tosca, "dramatically it is a good deal more depraved."[54] However, Sir Thomas Beecham once remarked that anything that Joseph Kerman said about Puccini "can safely be ignored".[55]

Some of this criticism is possibly due to the standard Alfano ending (Alfano II), in which Liù's death is followed almost immediately by Calaf's "rough wooing" of Turandot, and the "bombastic" end to the opera. A later attempt at completing the opera was made, with the co-operation of the publishers, Ricordi, in 2002 by Luciano Berio. The Berio version is considered to overcome some of these criticisms, but critics such as Michael Tanner have failed to be wholly convinced by the new ending, noting that the criticism by the Puccini advocate Julian Budden still applies: "Nothing in the text of the final duet suggests that Calaf's love for Turandot amounts to anything more than a physical obsession: nor can the ingenuities of Simoni and Adami's text for 'Del primo pianto' convince us that the Princess's submission is any less hormonal."[56]

Ashbrook and Powers consider it was an awareness of this problem – an inadequate buildup for Turandot's change of heart, combined with an overly successful treatment of the secondary character (Liù) – which contributed to Puccini's inability to complete the opera.[28] Another alternative ending, written by Chinese composer Hao Wei Ya, has Calaf pursue Turandot but kiss her tenderly, not forcefully; and the lines beginning "Del primo pianto" (Of the first tears) are expanded into an aria where Turandot tells Calaf more fully about her change of heart.[57][38][58]

Concerning the compelling believability of the self-sacrificial Liù character in contrast to the two mythic protagonists, biographers note echoes in Puccini's own life. He had had a servant named Doria, whom his wife accused of sexual relations with Puccini. The accusations escalated until Doria killed herself. In Turandot, Puccini lavished his attention on the familiar sufferings of Liù, as he had on his many previous suffering heroines. However, in the opinion of Father Owen Lee, Puccini was out of his element when it came to resolving the tale of his two allegorical protagonists. Finding himself completely outside his normal genre of verismo, he was incapable of completely grasping and resolving the necessary elements of the mythic, unable to "feel his way into the new, forbidding areas the myth opened up to him"[59] – and thus unable to finish the opera in the two years before his unexpected death.

Instrumentation[edit]

Turandot is scored for three flutes (the third doubling piccolo); two oboes; one cor anglais; two clarinets in B-flat; one bass clarinet in B-flat, two bassoons; one contrabassoon; two onstage alto saxophones in E-flat; four French horns in F; three trumpets in F; three tenor trombones; one contrabass trombone; six onstage trumpets in B-flat, three onstage trombones; and one onstage bass trombone; a percussion section with timpani, cymbals, gong, one triangle, one snare drum, one bass drum, one tam-tam, one glockenspiel, one xylophone, one bass xylophone, tubular bells, and tuned Chinese gongs;[60] one onstage wood block; one onstage large gong; one celesta; one pipe organ; two harps; and strings.

Citations

Sources