Unix philosophy

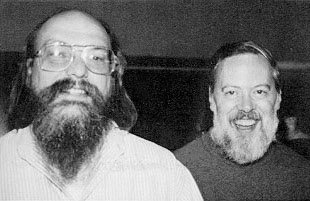

The Unix philosophy, originated by Ken Thompson, is a set of cultural norms and philosophical approaches to minimalist, modular software development. It is based on the experience of leading developers of the Unix operating system. Early Unix developers were important in bringing the concepts of modularity and reusability into software engineering practice, spawning a "software tools" movement. Over time, the leading developers of Unix (and programs that ran on it) established a set of cultural norms for developing software; these norms became as important and influential as the technology of Unix itself, and have been termed the "Unix philosophy."

The Unix philosophy emphasizes building simple, compact, clear, modular, and extensible code that can be easily maintained and repurposed by developers other than its creators. The Unix philosophy favors composability as opposed to monolithic design.

The Unix philosophy is documented by Doug McIlroy[1] in the Bell System Technical Journal from 1978:[2]

It was later summarized by Peter H. Salus in A Quarter-Century of Unix (1994):[1]

In their Unix paper of 1974, Ritchie and Thompson quote the following design considerations:[3]

Do One Thing and Do It Well[edit]

As stated by McIlroy, and generally accepted throughout the Unix community, Unix programs have always been expected to follow the concept of DOTADIW, or "Do One Thing And Do It Well." There are limited sources for the acronym DOTADIW on the Internet, but it is discussed at length during the development and packaging of new operating systems, especially in the Linux community.

Patrick Volkerding, the project lead of Slackware Linux, invoked this design principle in a criticism of the systemd architecture, stating that, "attempting to control services, sockets, devices, mounts, etc., all within one daemon flies in the face of the Unix concept of doing one thing and doing it well."[10]

In his book The Art of Unix Programming that was first published in 2003,[11] Eric S. Raymond (open source advocate and programmer) summarizes the Unix philosophy as KISS Principle of "Keep it Simple, Stupid."[12] He provides a series of design rules:[1]

Criticism[edit]

In a 1981 article entitled "The truth about Unix: The user interface is horrid"[13] published in Datamation, Don Norman criticized the design philosophy of Unix for its lack of concern for the user interface. Writing from his background in cognitive science and from the perspective of the then-current philosophy of cognitive engineering,[14] he focused on how end-users comprehend and form a personal cognitive model of systems—or, in the case of Unix, fail to understand, with the result that disastrous mistakes (such as losing an hour's worth of work) are all too easy.

In the podcast On the Metal, Jonathan Blow criticised UNIX philosophy as being outdated.[15] He argued that tying together modular tools results in very inefficient programs. He says that UNIX philosophy suffers from similar problems to microservices: without overall supervision, big architectures end up ineffective and inefficient.