Venezuelan crisis of 1902–1903

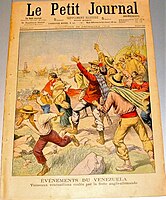

The Venezuelan crisis of 1902–1903[a] was a naval blockade imposed against Venezuela by Great Britain, Germany, and Italy from December 1902 to February 1903, after President Cipriano Castro refused to pay foreign debts and damages suffered by European citizens in recent Venezuelan civil wars. Castro assumed that the American Monroe Doctrine would see Washington intervene to prevent European military intervention. However, at the time, United States president Theodore Roosevelt and his Department of State saw the doctrine as applying only to European seizure of territory, rather than intervention per se. With prior promises that no such seizure would occur, the U.S. was officially neutral and allowed the action to go ahead without objection. The blockade saw Venezuela's small navy quickly disabled, but Castro refused to give in, and instead agreed in principle to submit some of the claims to international arbitration, which he had previously rejected. Germany initially objected to this, arguing that some claims should be accepted by Venezuela without arbitration.

President Roosevelt years later claimed he forced the Germans to back down by sending his own larger fleet under and threatening war if the Germans landed. However he made no preparations for war against a major power, nor did he alert officials at the State Department, War Department, Navy Department or the Senate.[1]

With Castro failing to back down, U.S. pressure and increasingly negative British and American press reaction to the affair, the blockading nations agreed to a compromise, but maintained the blockade during negotiations over the details. This led to the signing of an agreement on 13 February 1903 which saw the blockade lifted, and Venezuela commit 30% of its customs duties to settling claims.

When the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague subsequently awarded preferential treatment to the blockading powers against the claims of other nations, the U.S. feared this would encourage future European intervention. The episode contributed to the development of the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, asserting a right of the United States to intervene to stabilize the economic affairs of small states in the Caribbean and Central America if they were unable to pay their international debts, in order to preclude European intervention to do so.

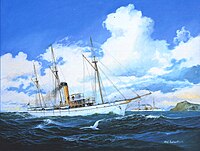

It remains disputed to this day how the Anglo-German cooperation on Venezuela came about, with varying opinions as to the source of the initiative.[b] In mid-1901, with the distraction of the Boxer Rebellion gone, Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow decided to respond to the German concerns in Venezuela with some form of military intervention, and discussed with the German navy the feasibility of a blockade. Admiral Otto von Diederichs was keen, and recommended occupying Caracas if a blockade didn't succeed. However, disagreements within the German government over whether a blockade should be pacific (permitting neutral ships to pass) or martial (enabling them to be seized) caused delays, and in any case the German Emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, was unconvinced regarding military action.[12] Nonetheless, in late 1901 a renewed demand for reparations was backed up by a show of naval strength, with SMS Vineta and Falke sent to the Venezuelan coast.[11] In January 1902 the Kaiser declared a delay to any blockade due to the outbreak of another civil war in Venezuela (led by financier Manuel Antonio Matos) which raised the possibility of a more amenable government.[11][c] Complicating matters were rumours "rampant in the United States and in England" that Germany wanted Margarita Island as a South American naval base; however a May 1900 visit by the German cruiser SMS Vineta had concluded it was unsuitable, and the German navy had become more conscious of how vulnerable such far-flung bases would be.[12] In late 1901, the British Foreign Office became concerned that Britain would look bad if it failed to defend its citizens' interests while Germany took care of theirs, and began sounding out the Germans about a possible common action, initially receiving a negative response.[8] By early 1902, British and German financiers were working together to pressure their respective governments into action.[13] The Italians, who had begun to suspect the existence of plans to enforce debts, sought to be involved too, but Berlin refused. Their participation was agreed to by the British "after Rome had shrewdly pointed out that it could repay the favor in Somalia".[14] The Italians quickly sent the armoured cruiser Carlo Alberto and the protected cruisers Giovanni Bausan and Etna toward the Venezuela coast.

In June 1902, Castro seized a British ship, The Queen, on suspicion of aiding rebels, in another phase of the Venezuelan civil war. This, together with Castro's failure to engage with the British through diplomatic channels, tilted the balance in London in favor of action, with or without German cooperation.[8] By July 1902, the German government was ready to return to the possibility of joint action, with Matos' insurrection having led to further abuses against German citizens and their property, including by government forces.[13] In mid-August, Britain and Germany agreed in principle to go ahead with a blockade later in the year.[15] In September, after the Haitian rebel ship Crête-à-Pierrot hijacked a German ship and seized weapons destined for the Haitian government, Germany sent the gunboat SMS Panther to Haiti.[16] Panther found the ship and declared that it would sink it, after which the rebel Admiral Hammerton Killick, after evacuating the crew, blew up his ship and himself with it, assisted by fire from Panther.[16] There were concerns about how the United States would view the action in the context of the Monroe Doctrine, but despite U.S. State Department legal advice describing the sinking as "illegal and excessive", the State Department endorsed the action, and The New York Times declared that "Germany was quite within her rights in doing a little housecleaning on her own account".[16] Similarly, the British acquisition of the island of Patos, in the mouth of the Orinoco between Venezuela and the British dependency of Trinidad and Tobago, seemed to cause no concern in Washington, even though as a territorial claim it "skirted dangerously close to challenging the Monroe Doctrine".[17]

On 11 November, at a visit of Kaiser Wilhelm's to his uncle King Edward VII at Sandringham House, an "iron-clad" agreement was signed, albeit leaving key details unresolved beyond the first step of seizing Venezuela's gunboats.[15] The agreement specified that matters with Venezuela should be resolved to the satisfaction of both countries, precluding the possibility of Venezuela making a deal with just one.[15] The agreement was motivated not least by German fears that Britain might withdraw from action, and leave Germany exposed to U.S. anger.[18] The British press reaction to the deal was highly negative, with the Daily Mail declaring that Britain was now "bound by a pledge to follow Germany in any wild enterprise which the German government may think it proper to undertake".[15] In the course of 1902 the U.S. received various indications from Britain, Germany and Italy of an intention to take action, with the U.S. declaring that as long as no territorial acquisition were made, it would not oppose any action.[19] The British minister in Venezuela emphasized the need for secrecy about the plans, saying that he thought the U.S. minister would leak warning to Castro, which would give Castro the opportunity to hide Venezuela's gunboats up the Orinoco River.[20]

On 7 December 1902, both London and Berlin issued ultimatums to Venezuela, even though there was still disagreement about whether to impose a pacific blockade (as the Germans wanted) or a war blockade (as the British wanted).[21] Germany ultimately agreed to a war blockade, and after receiving no reply to their ultimatums, an unofficial naval blockade was imposed on 9 December with SMS Panther, SMS Falke, SMS Gazelle and SMS Vineta as major Kaiserliche Marine warships in Caribbean Sea.[21] On 11 December, Italy offered its own ultimatum,[22] which Venezuela also rejected. Venezuela maintained that its national laws were final, and said "the so-named foreign debt ought not to be and never had been a matter of discussion beyond the legal guaranties found in the law of Venezuela on the public debt".[23]