Geist

Geist (German pronunciation: [ˈɡaɪst] ⓘ) is a German noun with a significant degree of importance in German philosophy. Geist can be roughly translated into three English meanings: ghost (as in the spooky creature), spirit (as in the Holy Spirit), and mind or intellect. Some English translators resort to using "spirit/mind" or "spirit (mind)" to help convey the meaning of the term.[1]

This article is about the German word. For other uses, see Geist (disambiguation).Geist is also a central concept in Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's 1807 The Phenomenology of Spirit (Phänomenologie des Geistes). Notable compounds, all associated with Hegel's view of world history of the late 18th century, include Weltgeist (German: [ˈvɛltˌɡaɪ̯st] ⓘ, "world-spirit"), Volksgeist "national spirit" and Zeitgeist "spirit of the age".

Hegelianism[edit]

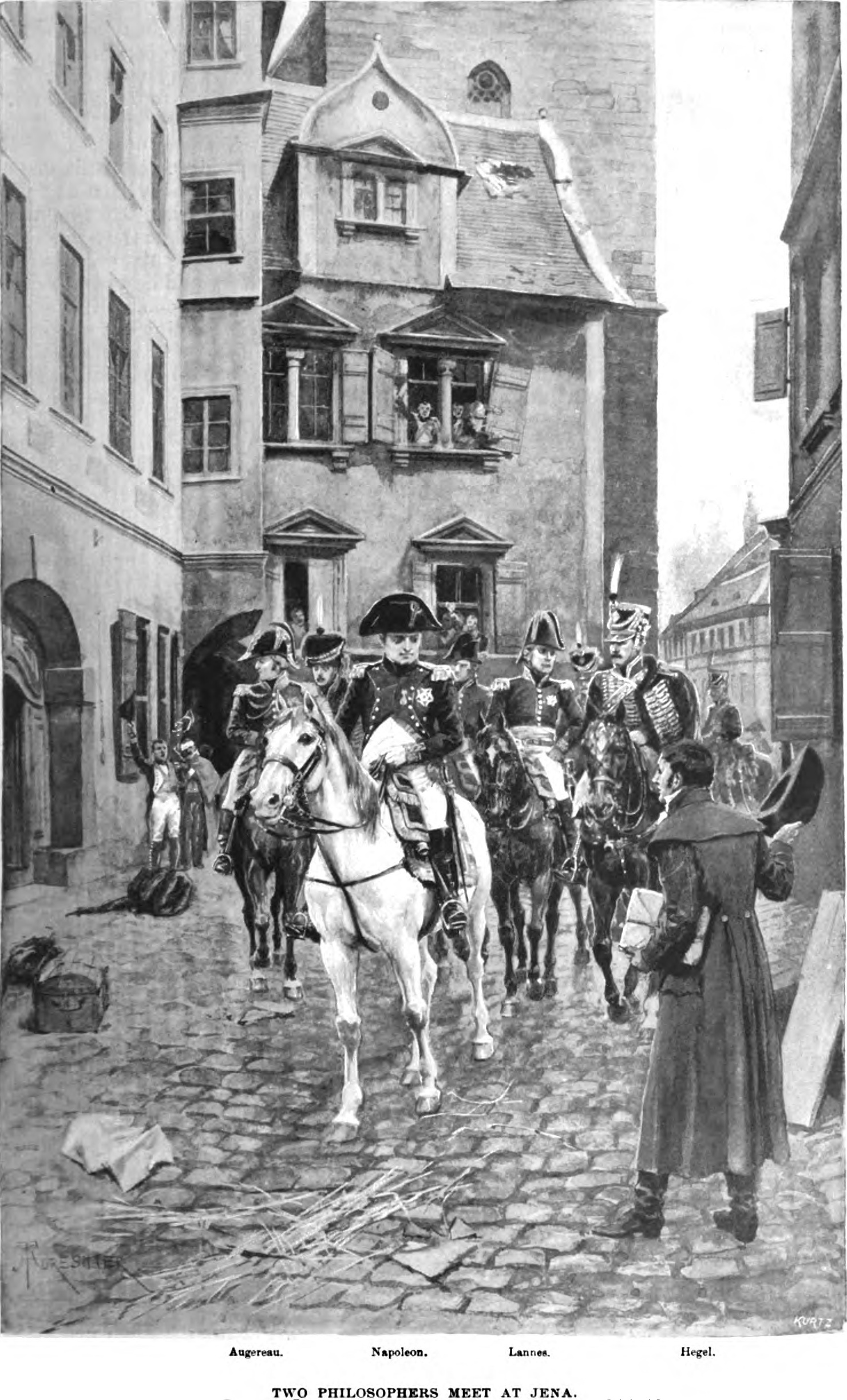

Geist is a central concept in Hegel's philosophy. According to most interpretations, the Weltgeist ("world spirit") is not an actual object or a transcendent, godlike thing, but a means of philosophizing about history. Weltgeist is effected in history through the mediation of various Volksgeister ("national spirits"), the great men of history, such as Napoleon, are the "concrete universal".

This has led some to claim that Hegel favored the great man theory, although his philosophy of history, in particular concerning the role of the "universal state" (Universalstaat, which means a universal "order" or "statute" rather than "state"), and of an "End of History" is much more complex.

For Hegel, the great hero is unwittingly utilized by Geist or absolute spirit, by a "ruse of reason" as he puts it, and is irrelevant to history once his historic mission is accomplished; he is thus subjected to the teleological principle of history, a principle which allows Hegel to reread the history of philosophy as culminating in his philosophy of history.