Russian Revolution of 1905

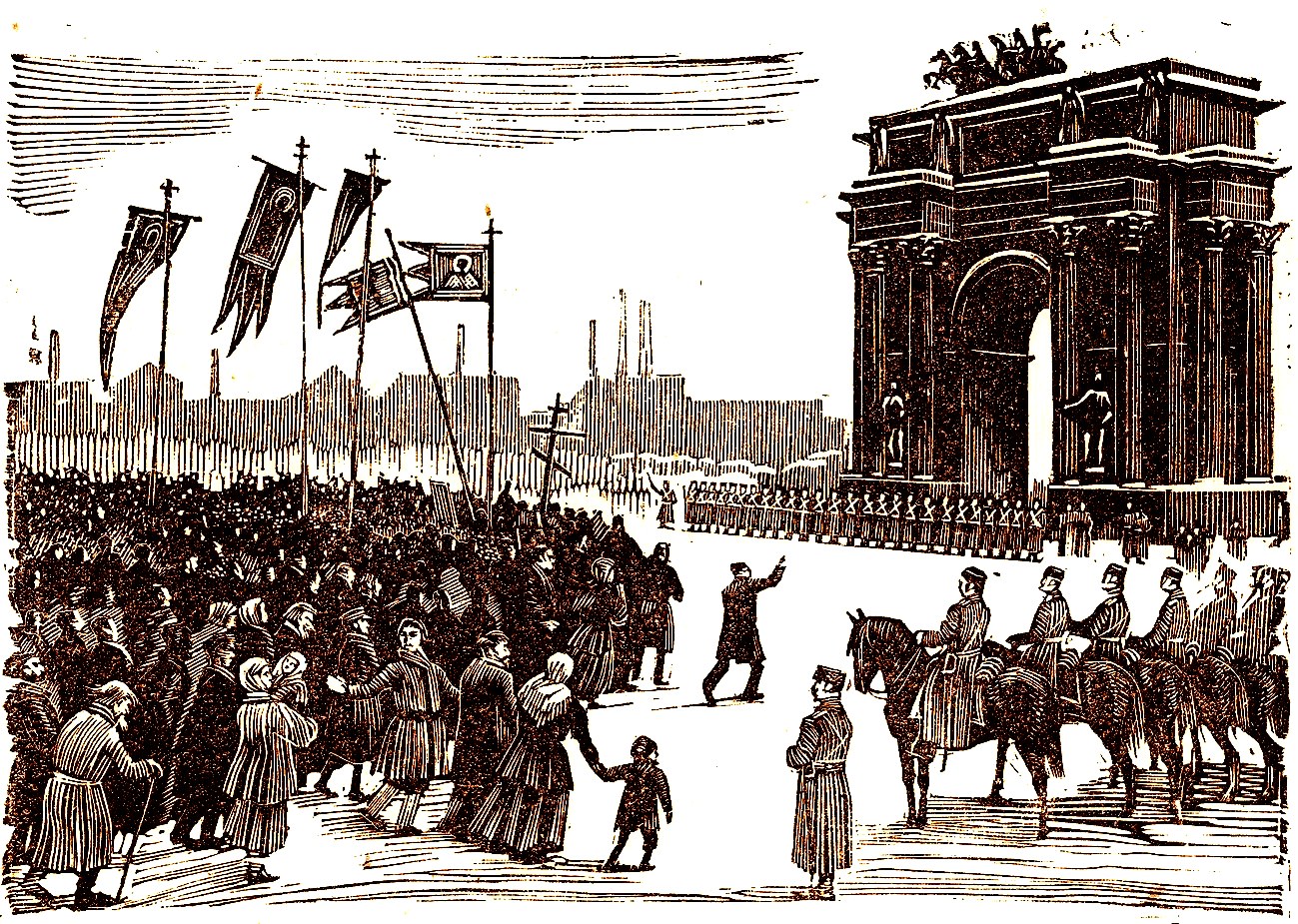

The Russian Revolution of 1905,[b] also known as the First Russian Revolution,[c] began on 22 January 1905. A wave of mass political and social unrest then began to spread across the vast areas of the Russian Empire. The unrest was directed primarily against the Tsar, the nobility, and the ruling class. It included worker strikes, peasant unrest, and military mutinies. In response to the public pressure, Tsar Nicholas II was forced to go back on his earlier authoritarian stance and enact some reform (issued in the October Manifesto). This took the form of establishing the State Duma, the multi-party system, and the Russian Constitution of 1906. Despite popular participation in the Duma, the parliament was unable to issue laws of its own, and frequently came into conflict with Nicholas. The Duma's power was limited and Nicholas continued to hold the ruling authority. Furthermore, he could dissolve the Duma, which he did three times in order to get rid of the opposition.[3]

The 1905 revolution was set off by the international humiliation that resulted from the Russian defeat in the Russo-Japanese War, which ended in the same year. Calls for revolution were intensified by the growing realisation by a variety of sectors of society of the need for reform. Politicians such as Sergei Witte had succeeded in partially industrializing Russia but failed to adequately meet the needs of the population. Tsar Nicholas II and the monarchy narrowly survived the Revolution of 1905, but its events foreshadowed what was to come in the 1917 Russian Revolution.

Many historians contend that the 1905 revolution set the stage for the 1917 Russian Revolutions, which saw the monarchy abolished and the Tsar executed. Calls for radicalism were present in the 1905 revolution, but many of the revolutionaries who were in a position to lead were either in exile or in prison while it took place. The events in 1905 demonstrated the precarious position in which the Tsar found himself. As a result, Tsarist Russia did not undergo sufficient reform, which had a direct impact on the radical politics brewing in the Russian Empire. Although the radicals were still in the minority of the populace, their momentum was growing. Vladimir Lenin, a revolutionary himself, would later say that the Revolution of 1905 was "The Great Dress Rehearsal", without which the "victory of the October Revolution in 1917 would have been impossible".[4]

The years 1906 and 1907 saw a decline of mass movements, strikes and protests, and a rise of overt political violence. Combat groups such as the SR Combat Organization carried out many assassinations targeting civil servants and police, and robberies. Between 1906 and 1909, revolutionaries killed 7,293 people, of whom 2,640 were officials, and wounded 8,061.[74] Notable victims included:

Ivanovo Voznesensk was known as the 'Russian Manchester' for its textile mills.[80] In 1905, its local revolutionaries were overwhelmingly Bolshevik. It was the first Bolshevik branch in which workers outnumbered intellectuals.

Estonia[edit]

In the Governorate of Estonia, Estonians called for freedom of the press and assembly, for universal suffrage, and for national autonomy. On 29 October [O.S. 16 October], the Russian army opened fire in a meeting on a street market in Tallinn in which about 8 000–10 000 people participated, killing 94 and injuring over 200. The October Manifesto was supported in Estonia and the Estonian flag was displayed publicly for the first time. Jaan Tõnisson used the new political freedoms to widen the rights of Estonians by establishing the first Estonian political party – National Progress Party.

Another, more radical political organisation, the Estonian Social Democratic Workers' Union was founded as well. The moderate supporters of Tõnisson and the more radical supporters of Jaan Teemant could not agree about how to continue with the revolution, and only agreed that both wanted to limit the rights of Baltic Germans and to end Russification. The radical views were publicly welcomed and in December 1905, martial law was declared in Tallinn. A total of 160 manors were looted, resulting in ca. 400 workers and peasants being killed by the army. Estonian gains from the revolution were minimal, but the tense stability that prevailed between 1905 and 1917 allowed Estonians to advance the aspiration of national statehood.