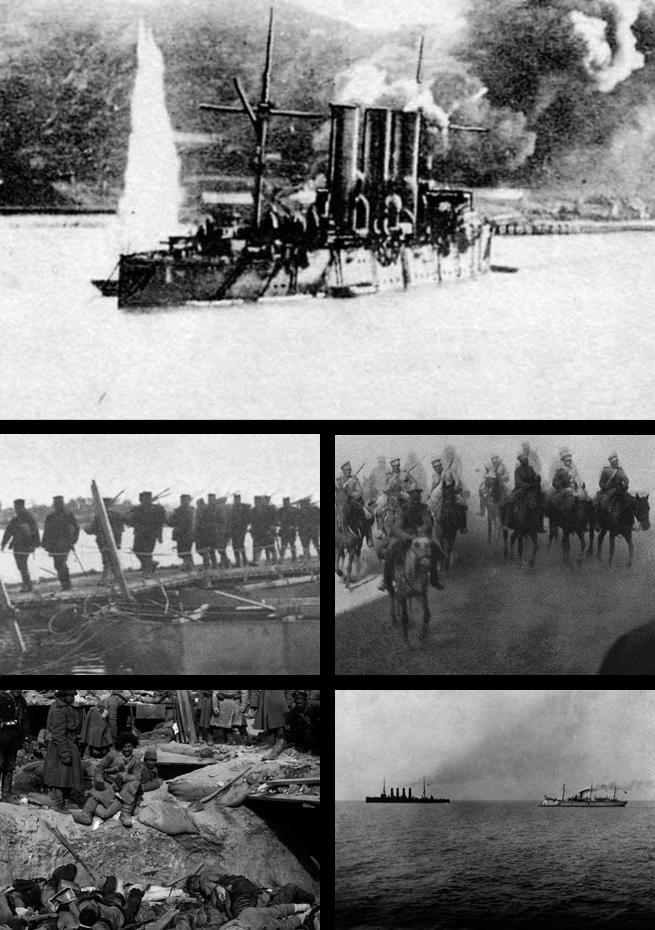

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (Japanese: 日露戦争, romanized: Nichiro sensō, lit. 'Japanese-Russian War'; Russian: русско-японская война, romanized: russko-yaponskaya voyna) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1905 over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire.[4] The major theatres of military operations were in the Liaodong Peninsula and Mukden in Southern Manchuria, the Yellow Sea and the Sea of Japan.

Not to be confused with Soviet–Japanese War.

Russia sought a warm-water port on the Pacific Ocean both for its navy and for maritime trade. Vladivostok remained ice-free and operational only during the summer; Port Arthur, a naval base in Liaodong Province leased to Russia by the Qing dynasty of China from 1897, was operational year round.

Russia had pursued an expansionist policy east of the Urals, in Siberia and the Far East, since the reign of Ivan the Terrible in the 16th century.[5]

Since the end of the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895, Japan had feared Russian encroachment would interfere with its plans to establish a sphere of influence in Korea and Manchuria.

Seeing Russia as a rival, Japan offered to recognize Russian dominance in Manchuria in exchange for recognition of the Korean Empire as being within the Japanese sphere of influence. Russia refused and demanded the establishment of a neutral buffer zone between Russia and Japan in Korea, north of the 39th parallel. The Imperial Japanese Government perceived this as obstructing their plans for expansion into mainland Asia and chose to go to war. After negotiations broke down in 1904, the Imperial Japanese Navy opened hostilities in a surprise attack on the Russian Eastern Fleet at Port Arthur, China on 9 February [O.S. 27 January] 1904. The Russian Empire responded by declaring war on Japan.

Although Russia suffered a number of defeats, Emperor Nicholas II remained convinced that Russia could still win if it fought on; he chose to remain engaged in the war and await the outcomes of key naval battles. As hope of victory dissipated, he continued the war to preserve the dignity of Russia by averting a "humiliating peace". Russia ignored Japan's willingness early on to agree to an armistice and rejected the idea of bringing the dispute to the Permanent Court of Arbitration at the Hague. After the decisive naval battle of Tsushima, the war was concluded with the Treaty of Portsmouth (5 September [O.S. 23 August] 1905), mediated by US President Theodore Roosevelt. The complete victory of the Japanese military surprised international observers and transformed the balance of power in both East Asia and Europe, resulting in Japan's emergence as a great power and a decline in the Russian Empire's prestige and influence in Europe. Russia's incurrence of substantial casualties and losses for a cause that resulted in humiliating defeat contributed to a growing domestic unrest which culminated in the 1905 Russian Revolution, and severely damaged the prestige of the Russian autocracy.

Status of Combatants[edit]

Japan[edit]

Japan had conducted detailed studies of the Russian Far East and Manchuria prior to the war and, as it was mandatory for Japanese officers to speak one foreign language, Japan had access to superior maps during the conflict. The Japanese army relied on conscription, introduced in 1873, to maintain its military strength and to provide a large army in times of war.[50] This system of conscription gave Japan a large pool of reserves to draw upon. The Active and 1st line reserve (the 1st line reserve was used to bring the active army to wartime strength) totalled 380,000; the 2nd line reserve contained 200,000; the conscript reserve a further 50,000; and the kokumin (akin to a national guard or militia) 220,000. This amounted to 850,000 trained troops available for service, in addition to 4,250,000 men in the untrained reserve.

Immediately available to Japan on the declaration of war were 257,000 infantry, 11,000 cavalry and 894 pieces of artillery. These figures were divided between the Imperial Guards division, 12 regular divisions, 2 cavalry brigades, 2 artillery brigades, 13 reserve brigades, depot troops and the garrison of Taiwan. A regular Japanese division contained 11,400 infantry, 430 cavalry and 36 guns - the guns being organised into batteries of 6. Though another 4 divisions and 4 reserve brigades were formed in 1904, no further formations were created as the reserves were used to replace losses sustained in combat. Japanese reserves were given a full year of training before entering combat, though as the war progressed this was reduced to 6 months due to high casualties. The Japanese army did not follow the European convention of implementing Corps, thus there were no corps troops or command and the Japanese divisions were immediately subordinate to armies.[51]

Olender gives a different appraisal of Japanese strength, maintaining that there were 350,000 men of the standing army and 1st reserve, with an additional 850,000 trained men in reserve, creating a total trained force of 1,200,000 men. The breakdown of the Japanese standing army is different too, with Olender giving each Japanese division 19,000 men including auxiliary troops; he also states that the 13 reserve brigades contained 8,000 men each and mentions 20 fortress battalions, which is omitted by Connaughton. It is further stated that the Japanese army possessed 1,080 field guns and between 120 and 150 heavy guns at the war's commencement.[52]

Japanese cavalry was not considered the elite of the army as was the case in Russia; instead Japanese cavalry primarily acted as scouts and fought dismounted, armed with carbine and sword; this was reflected in the fact that each cavalry brigade contained 6 machine guns.[51]

Russia[edit]

There is no consensus over how many Russian troops were present in the Far East around the time of the commencement of the war. One estimate states that the Russian army possessed 60,000 infantry 3,000 cavalry and 164 guns mostly at Vladivostok and Port Arthur with a portion at Harbin. This was reinforced by the middle of February to 95,000 with 45,000 at Vladivostok, 8,000 at Harbin, 9,000 at Haicheng, 11,000 on the Yalu River and 22,000 at Port Arthur.[53]

Olender gives the figure at 100,000 men including 8 infantry divisions, fortress troops and support troops. The entire Russian army in 1904 amounted to 1,200,000 men in 29 Corps. The Russian plan was immensely flawed as the Russians possessed only 24,000 potential reinforcements east of Lake Baikal when the war commenced. They would be reinforced by 35,000 men after 4 months and a further 60,000 men 10 months after the commencement of the war at which point they would take the offensive. This plan was based on the erroneous belief that the Japanese army could only mobilise 400,000 with them being unable to field more than 250,000 in an operational sense and 80,000-100,000 of their operational strength being necessary to secure supply lines and therefore only 150,000-170,000 Japanese soldiers would be available for field action. The possibility of Port Arthur being taken was dismissed entirely.[54]

An alternative figure for forces in the Far East is given at over 150,000 men and 266 guns, with Vladivostok and Port Arthur containing a combined force of 45,000 men and with an additional 55,000 engaged in guarding lines of communication, leaving only 50,000 troops to take the field.[55]

Unlike the Japanese, the Russians did utilise the Corps system and in fact maintained two distinct styles of Corps: the European and the Siberian. The two corps both possessed two divisions and their corresponding troop numbers, but a Siberian Division was much smaller, containing only 3,400 men and 20 guns, with a corps containing around 12,000 men and lacking both artillery and divisional guns. Russia only possessed two Siberian Corps, both unprepared for war. After war was declared, this number was raised to seven as the conflict progressed. The European Corps in comparison contained 28,000 soldiers and 112 guns with 6 such corps sent to the Far East during the war - a further three being dispatched that did not arrive before the war ended.[53][56]

Russian Logistics were hampered by the fact that the only connection to European Russia was the Trans-Siberian Railway, which remained incomplete as at Lake Baikal the railway was not connected. A single train would take between 15 and 40 days to traverse the railway, with 40 days being the more common figure. A single battalion would take a month to transport from Moscow to Shenyang. After the line's eventual completion, 20 trains ran daily and by the conclusion of the war some 410,000 soldiers, 93,000 horses and 1,000 guns had been carried down it.[53]

The tactics utilised by the Russians were as outdated as their doctrine. The Russian infantry were holding to the maxim of Suvorov over a century after his death. The Russian command still used strategies from the Crimean war, attacking en echelon across a wide front in closed formations; it was not uncommon for Russian higher command to bypass their intermediate commanders and issue orders directly to battalions, thus creating confusion during combat.[57]

Declaration of war[edit]

Japan issued a declaration of war on 8 February 1904.[59] However, three hours before Japan's declaration of war was received by the Russian government, and without warning, the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the Russian Far East Fleet at Port Arthur.[60]

Tsar Nicholas II was stunned by news of the attack. He could not believe that Japan would commit an act of war without a formal declaration, and had been assured by his ministers that the Japanese would not fight. When the attack came, according to Cecil Spring Rice, first secretary at the British Embassy, it left the Tsar "almost incredulous".[61]

Russia declared war on Japan eight days later.[62] Japan, in response, made reference to the Russian attack on Sweden in 1808 without declaration of war, although the requirement to mediate disputes between states before commencing hostilities was made international law in 1899, and again in 1907, with the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907.[63][64][65]

The Principality of Montenegro also declared war on Japan in gratitude for Russia's political support of the Montenegrin prince. The gesture was symbolic and no soldiers from the army were ever deployed in the far East but a few Montenegrins volunteered and joined the Russian army.[66]

The Qing Empire favoured the Japanese position and even offered military aid, but Japan declined it. However, Yuan Shikai sent envoys to Japanese generals several times to deliver foodstuffs and alcoholic drinks. Native Manchurians joined the war on both sides as hired troops.[67]