1954 Geneva Conference

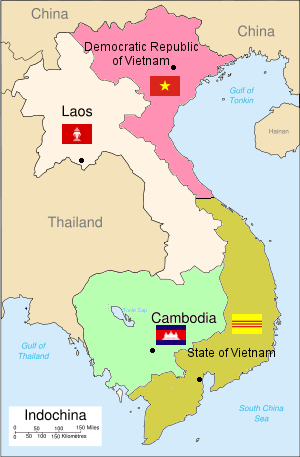

The Geneva Conference was a conference that was intended to settle outstanding issues resulting from the Korean War and the First Indochina War and involved several nations. It took place in Geneva, Switzerland, from 26 April to 20 July 1954.[1][2] The part of the conference on the Korean question ended without adopting any declarations or proposals and so is generally considered less relevant. On the other hand, the Geneva Accords that dealt with the dismantling of French Indochina proved to have long-lasting repercussions. The crumbling of the French colonial empire in Southeast Asia led to the formation of the states of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam), the State of Vietnam (precursor of the future Republic of Vietnam, or South Vietnam), the Kingdom of Cambodia, and the Kingdom of Laos. Three agreements about French Indochina, covering Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, were signed on 21 July 1954 and took effect two days later.

For other similar events, see Geneva Conference.Diplomats from South Korea, North Korea, the People's Republic of China, the Soviet Union, and the United States dealt with the Korean side of the conference. For the Indochina side, the Accords were between France, the Viet Minh, the Soviet Union, the People's Republic of China, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the future states being made from French Indochina.[3] The agreement temporarily separated Vietnam into two zones: a northern zone to be governed by the Viet Minh and a southern zone to be governed by the State of Vietnam, which was headed by former Nguyễn dynasty emperor Bảo Đại. A Conference Final Declaration, which was issued by the British chairman of the conference, provided that a general election be held by July 1956 to create a unified Vietnamese state. Despite helping create some of the agreements, they were not directly signed or accepted by delegates of the State of Vietnam and the United States. After a military buildup in North Vietnam, the State of Vietnam, under Ngo Dinh Diem, subsequently withdrew from the proposed elections. Worsening relations between the North and South would eventually lead to the Vietnam War.

Korea[edit]

The South Korean representative proposed that the South Korean government was the only legal government in Korea, that UN-supervised elections should be held in the North, that Chinese forces should withdraw, and that UN forces, a belligerent party in the war, should remain as a police force. The North Korean representative suggested that elections be held throughout all of Korea, that all foreign forces leave beforehand, that the elections be run by an all-Korean Commission to be made up of equal parts from North and South Korea, and to increase general relations economically and culturally between the North and the South.[8]

The Chinese delegation proposed an amendment have a group of 'neutral' nations supervise the elections, which the North accepted. The U.S. supported the South Korean position, saying that the USSR wanted to turn North Korea into a puppet state. Most allies remained silent and at least one, Britain, thought that the South Korean–U.S. proposal would be deemed unreasonable.[8]

The South Korean representative proposed that all-Korea elections, be held according to South Korean constitutional procedures and still under UN supervision. On June 15, the last day of the conference on the Korean question, the USSR and China both submitted declarations in support of a unified, democratic, independent Korea, saying that negotiations to that end should resume at an appropriate time. The Belgian and British delegations said that while they were not going to accept "the Soviet and Chinese proposals, that did not mean a rejection of the ideas they contained".[9] In the end, however, the conference participants did not agree on any declaration.

The accords, which were issued on July 21, 1954 (taking effect two days later),[21] set out the following terms in relation to Vietnam:

The agreement was signed by the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, France, the People's Republic of China, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom. The State of Vietnam rejected the agreement,[24] while the United States stated that it "took note" of the ceasefire agreements and declared that it would "refrain from the threat or use of force to disturb them.[4]: 606

To put aside any notion specifically that the partition was permanent, an unsigned Final Declaration, stated in Article 6: "The Conference recognizes that the essential purpose of the agreement relating to Vietnam is to settle military questions with a view to ending hostilities and that the military demarcation line is provisional and should not in any way be interpreted as constituting a political or territorial boundary."[22]

Separate accords were signed by the signatories with the Kingdom of Cambodia and the Kingdom of Laos in relation to Cambodia and Laos respectively. Following the terms of the agreement, Laos would be governed by the Khao royal court while Cambodia would be ruled by the royal court of Norodom Sihanouk. Despite retaining its monarchy, the agreement also allowed for "VWP-affiliated Laotian forces" to run the provinces of Sam Neua and Phongsal, further expanding North Vietnamese influence within Indochina. Communist forces in Cambodia, however, would remain out of power. [5]: 99

The British and Communist Chinese delegations reached an agreement on the sidelines of the Conference to upgrade their diplomatic relations.[25]

Reactions[edit]

The DRV at Geneva accepted a much worse settlement than the military situation on the ground indicated. "For Ho Chi Minh, there was no getting around the fact that his victory, however unprecedented and stunning was incomplete and perhaps temporary. The vision that had always driven him on, that of a 'great union' of all Vietnamese, had flickered into view for a fleeting moment in 1945–46, then had been lost in the subsequent war. Now, despite vanquishing the French military, the dream remained unrealized ..."[4]: 620 That was partly as a result of the great pressure exerted by China (Pham Van Dong is alleged to have said in one of the final negotiating sessions that Zhou Enlai double-crossed the DRV) and the Soviet Union for their own purposes, but the Viet Minh had their own reasons for agreeing to a negotiated settlement, principally their own concerns regarding the balance of forces and fear of U.S. intervention.[4]: 607–9

France had achieved a much better outcome than could have been expected. Bidault had stated at the beginning of the Conference that he was playing with "a two of clubs and a three of diamonds" whereas the DRV had several aces, kings, and queens,[4]: 607 but Jean Chauvel was more circumspect: "There is no good end to a bad business."[4]: 613

In a press conference on July 21, President Eisenhower expressed satisfaction that a ceasefire had been concluded but stated that the U.S. was not a party to the Accords or bound by them, as they contained provisions that his administration could not support.[4]: 612