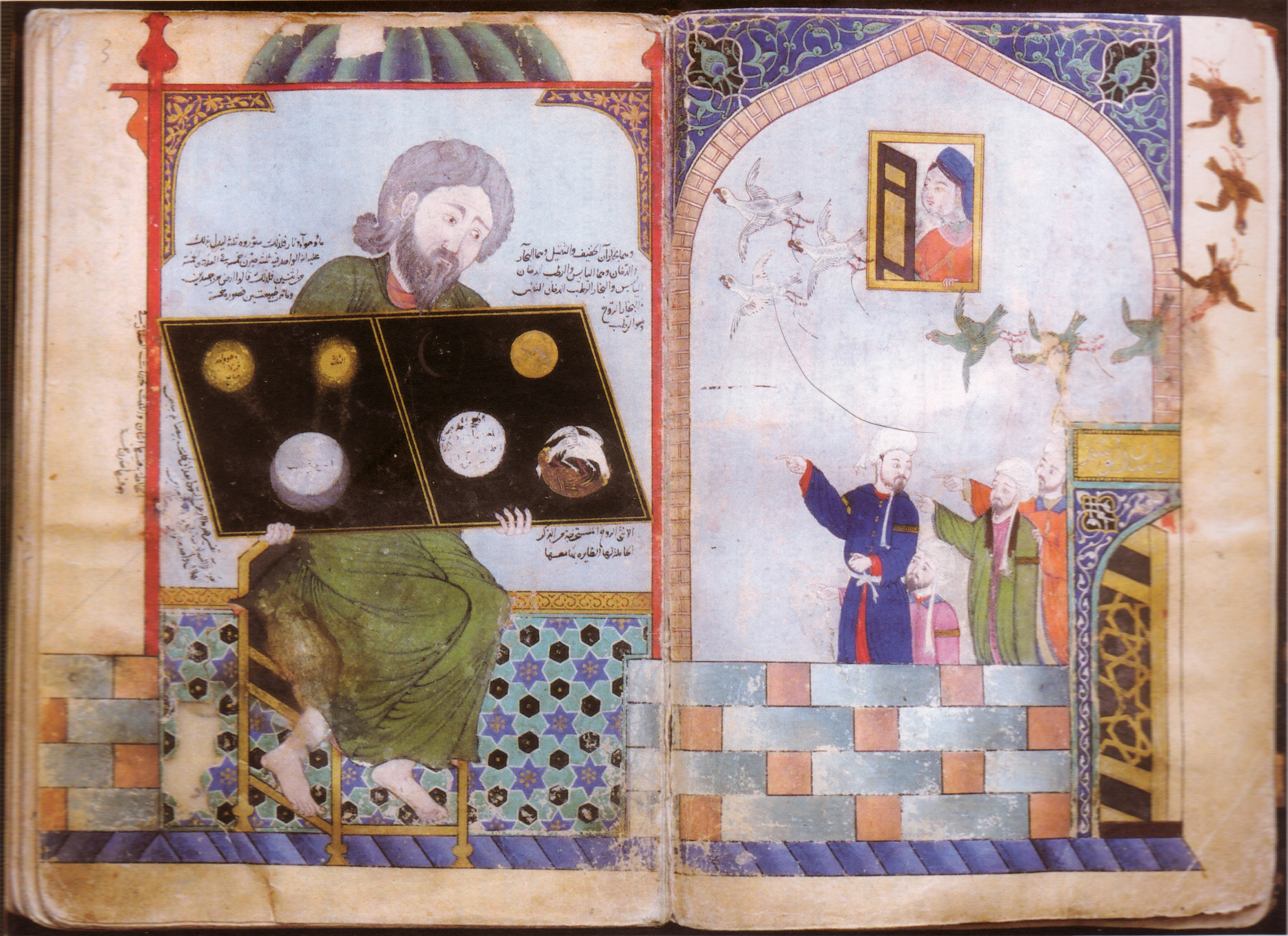

Alchemy in the medieval Islamic world

Alchemy in the medieval Islamic world refers to both traditional alchemy and early practical chemistry (the early chemical investigation of nature in general) by Muslim scholars in the medieval Islamic world. The word alchemy was derived from the Arabic word كيمياء or kīmiyāʾ[1][2]: 854 and may ultimately derive from the ancient Egyptian word kemi, meaning black.[2]

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the Islamic conquest of Roman Egypt, the focus of alchemical development moved to the Caliphate and the Islamic civilization. Much more is known about Islamic alchemy as it was better documented; most of the earlier writings that have come down through the years were preserved as Arabic translations.[3]

Alchemists and works[edit]

Khālid ibn Yazīd[edit]

According to the bibliographer Ibn al-Nadīm, the first Muslim alchemist was Khālid ibn Yazīd, who is said to have studied alchemy under the Christian Marianos of Alexandria. The historicity of this story is not clear; according to M. Ullmann, it is a legend.[12][13] According to Ibn al-Nadīm and Ḥajjī Khalīfa, he is the author of the alchemical works Kitāb al-kharazāt (The Book of Pearls), Kitāb al-ṣaḥīfa al-kabīr (The Big Book of the Roll), Kitāb al-ṣaḥīfa al-saghīr (The Small Book of the Roll), Kitāb Waṣīyatihi ilā bnihi fī-ṣ-ṣanʿa (The Book of his Testament to his Son about the Craft), and Firdaws al-ḥikma (The Paradise of Wisdom), but again, these works may be pseudepigraphical.[14][13][12]

Al-Rāzī mentions the following chemical processes: distillation, calcination, solution, evaporation, crystallization, sublimation, filtration, amalgamation, and ceration (a process for making solids pasty or fusible.)[34] Some of these operations (calcination, solution, filtration, crystallization, sublimation and distillation) are also known to have been practiced by pre-Islamic Alexandrian alchemists.[35]

In his Secretum secretorum, Al-Rāzī mentions the following equipment:[36]