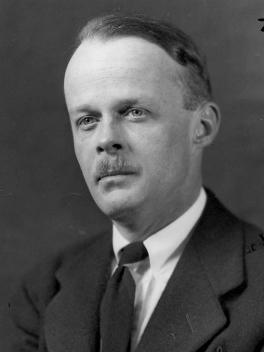

Allen Tate

John Orley Allen Tate (November 19, 1899 – February 9, 1979), known professionally as Allen Tate, was an American poet, essayist, social commentator, and poet laureate from 1943 to 1944. Among his best known works are the poems "Ode to the Confederate Dead" (1928) and "The Mediterranean" (1933), and his only novel The Fathers (1938). He is associated with New Criticism, the Fugitives and the Southern Agrarians.

For the American vocalist and songwriter, see Allen Tate (musician).

Allen Tate

November 19, 1899

Winchester, Kentucky, U.S.

February 9, 1979 (aged 79)

Nashville, Tennessee, U.S.

Poet, essayist

Poetry, literary criticism

Life[edit]

Early years[edit]

Tate was born near Winchester, Kentucky, to John Orley Tate, a Kentucky businessman and Eleanor Parke Custis Varnell from Virginia. On the Bogan side of her grandmother's family, Eleanor Varnell was a distant relative of George Washington; she left Tate a copper luster pitcher that Washington had ordered from London for his sister.

In 1916 and 1917 Tate studied the violin at the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music.

College and the Fugitives[edit]

Tate entered Vanderbilt University in 1918. He was the first undergraduate to be invited to join a group of men who met regularly to read and discuss their poetry: they included John Crowe Ransom and Donald Davidson on the faculty; James M. Frank, a prominent Nashville businessman who hosted the meetings; and Sidney Mttron Hirsch, a mystic and playwright, who presided.[1] Tate graduated Vanderbilt in 1922 with a B.A. magna cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa.

In 1922, the group began publishing a poetry magazine named The Fugitive, so the group was known as the Fugitives. Tate took along a younger friend to some meetings, sophomore Robert Penn Warren, who was invited to become a member in 1923.[2] The aim of the group, according to the critic J. A. Bryant, was "to demonstrate that a group of southerners could produce important work in the medium [of poetry], devoid of sentimentality and carefully crafted," and they wrote in the formalist tradition that valued the skillful use of meter and rhyme.[3]

When Robert Penn Warren left Southwestern College to accept a position at Louisiana State University, he recommended Tate to replace him. Tate accepted the position, and spent 1934 through 1936 there as lecturer in English.

1920s[edit]

Tate made his debut as a critic in the weekly book page Davidson edited for the Nashville Tennessean, publishing 29 reviews there during 1924. The fifth book he reviewed was An Anthology of Verse by American Negroes, edited by Newman Ivey White and Walter Clinton Jackson--"the first significant attempt" by "white critics to do justice to Negro literature in America." He faulted the editors' standards of "refinement" and "taste." "This of Claude McKay: 'Some of his poems are too erotic for good taste and conventional morality.' Whose good taste and whose morality?" It was easy "to understand why they overlooked altogether the work of Jean Toomer. Toomer is the finest Negro literary artist that has yet appeared in the American scene, but he is interested in the interior of Negro life, not in the pressure of American culture on the Negro."

In 1924, Tate moved to New York City where he met poet Hart Crane, with whom he had been corresponding for some time. Over a four-year period, Tate worked freelance for The Nation, and contributed to the Hound & Horn, Poetry magazine, and others. To make ends meet, he worked as a janitor.

During a summer visit with the poet Robert Penn Warren in Kentucky, he began a relationship with writer Caroline Gordon. The two lived together in Greenwich Village, but moved with Crane to a house in Patterson, New York, near "Robber Rocks," the home of friends Slater Brown and Sue Brown. Tate married Gordon in New York in May 1925. Their daughter Nancy was born in September. In 1928, along with other New York City friends, Tate went to Europe. In London, he visited with T. S. Eliot, whose poetry and criticism he greatly admired, and he also visited Paris.

In 1928, Tate published his first book of poetry, Mr. Pope and Other Poems, which contained his most famous poem, "Ode to the Confederate Dead" (not to be confused with "Ode to the Confederate Dead at Magnolia Cemetery" by the poet Henry Timrod). That same year, Tate also published the biography Stonewall Jackson: The Good Soldier. Later he became tired of the "Ode."

Just before leaving for Europe in 1928, Tate described himself to John Gould Fletcher as "an enforced atheist".[4] He later told Fletcher, "I am an atheist, but a religious one — which means that there is no organization for my religion." He regarded secular attempts to develop a system of thought for the modern world as misguided. "Only God," he insisted, "can give the affair a genuine purpose."[5] In his essay "The Fallacy of Humanism" (1929), Tate criticized the humanists of his time for creating a value system without investing it with any identifiable source of authority. "Religion is the only technique for the validation of values," he wrote.[6] Although he was attracted to Roman Catholicism, he deferred converting. Louis D. Rubin, Jr. observes that Tate may have waited "because he realized that for him at this time it would be only a strategy, an intellectual act".[7]

In 1929, Tate published a second biography, Jefferson Davis: His Rise and Fall.

1930s[edit]

After two years abroad, the Tates returned to the United States in 1930. During two months in New York, Tate secured a publisher for a symposium on the South and agrarianism that he and Ransom, Davidson, Andrew Lytle, and others had been planning. In Tennessee, the Tates took up residence at Benfolly in Clarksville, Tennessee|[8] an antebellum mansion with a 185-acre estate attached. Allen's brother Ben Tate, "who had made a lot of northern money out of coal.", purchased the house for them. House guests at Benfolly were frequent: Ford Madox Ford, Edmund Wilson, Louise Bogan, Phelps Putnam, Stark Young, the Howard Bakers, the Malcolm Cowleys, the Ransoms, the Warrens.[9]

Meeting at Benfolly and in Nashville, Tate, Ransom, Davidson et al. completed work on their symposium, I'll Take My Stand by Twelve Southerners, published in 1930. Tate didn't like the title; he had argued for "Tracts Against Communism." His contribution was "Remarks on the southern Religion": the Old South was a feudal society "without a feudal religion"; her Protestant "religious mind was inarticulate, dissenting, and schismatical."

In 1933 Lincoln Kirstein, co-founder and editor of Hound & Horn, wrote Tate, the Southern editor, that he "would like very much to know what all you people think could be done in relation to black and white." . . . Was the friction "inevitably racial, or accidentally economic?" Why were sexual relations between a white man and a black woman tolerated but not the reverse? Tate stated that there was "absolutely no 'solution' to the race problem in the South. That is, there is no solution that will remove the tension and the oppression that the negro must feel. . . . When two such radically different races live together, one must rule. I think the negro race is an inferior race." The key was social order, which served not social justice but "legal justice for the ruled race. . . . Liberal agitators" deprived "the negro of even the legal justice." Liberal policy was like "that of the Reconstruction, . . . a steady campaign against the Southern social system . . . to crush absolutely the remaining power of independent agriculture." As for the sexual question, "it is upon the sexual consent of women that the race depends for the future. . . . Under the industrial capitalist regime . . . women are no longer the very center of the social system. . . . What is to be done about all this I do not know; and I am inclined to think no one else knows."

During this time, Tate also became the de facto associate editor of The American Review, which was published and edited by Seward Collins. Tate believed The American Review could popularize the work of the Southern Agrarians. He objected to Collins's open support of Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, and condemned Fascism in an article in The New Republic in 1936. Much of Tate's major volumes of poetry were published in the 1930s, and the scholar David Havird describes this publication history in poetry as follows:

Attitudes on race[edit]

Literary scholars have questioned the relationship between the cultural attitudes of Modernist poets on issues such as race and the writing produced by the poets. The 1930s saw Tate's most notable stances on matters that may or may not be connected to literary craft. For example, though Tate spoke well of the work of fellow Modernist poet Langston Hughes, in 1931, Tate pressured his colleague Thomas Dabney Mabry, Jr., into canceling a reception for Hughes, comparing the idea of socializing with the black poet to meeting socially with his black cook.[15] John L. Grigsby describes Tate as a rare "nonracist equalitarian" among the Southern Agrarians.[16]

In the 1930s Tate held prejudices against blacks. He expressed views against interracial marriage and miscegenation and refused to associate with black writers (like Langston Hughes).[17][15] Tate also believed in white supremacy.[18][19][20] Underwood (p. 291) doesn't, however, quote Lincoln Kirstein's reply to Tate's letter (see the 1930)s: "The most lucid and carefully thought out attitude that I have ever seen in regard to the whole business."

According to the critic Ian Hamilton, Tate and his co-agrarians had been more than ready at the time to overlook the anti-Semitism of the American Review in order to promote their 'spiritual' defense of the Deep South's traditions. In a 1934 review, "A View of the Whole South",[21] Tate reviews W. T. Couch's "Culture in The South: A Symposium by Thirty-one Authors" and defends racial hegemony: "I argue it this way: the white race seems determined to rule the Negro race in its midst; I belong to the white race; therefore I intend to support white rule. Lynching is a symptom of weak, inefficient rule; but you can't destroy lynching by fiat or social agitation; lynching will disappear when the white race is satisfied that its supremacy will not be questioned in social crises."[18][19]

According to David Yezzi, who teaches at Johns Hopkins University, Tate held the conventional social views of a white Southerner in 1934: an "inherited racism, a Southern legacy rooted in place and time that Tate later renounced."[22] Tate was born of a Scotch-Irish lumber manager whose business failures required moving several times per year, Tate said of his upbringing ""we might as well have been living, and I been born, in a tavern at a crossroads."[23] However, his views on race were not passively incorporated; Thomas Underwood documents Tate's pursuit of racist ideology: "Tate also drew ideas from nineteenth-century proslavery theorists such as Thomas Roderick Dew, a professor at The College of William and Mary, and William Harper, of the University of South Carolina — "We must revive these men, he said."[20] In the 1930s Tate was infuriated when another writer implied that he was a fascist.