Ancient Egyptian deities

Ancient Egyptian deities are the gods and goddesses worshipped in ancient Egypt. The beliefs and rituals surrounding these gods formed the core of ancient Egyptian religion, which emerged sometime in prehistory. Deities represented natural forces and phenomena, and the Egyptians supported and appeased them through offerings and rituals so that these forces would continue to function according to maat, or divine order. After the founding of the Egyptian state around 3100 BC, the authority to perform these tasks was controlled by the pharaoh, who claimed to be the gods' representative and managed the temples where the rituals were carried out.

"Gods of Egypt" redirects here. For the 2016 fantasy film, see Gods of Egypt (film).

The gods' complex characteristics were expressed in myths and in intricate relationships between deities: family ties, loose groups and hierarchies, and combinations of separate gods into one. Deities' diverse appearances in art—as animals, humans, objects, and combinations of different forms—also alluded, through symbolism, to their essential features.

In different eras, various gods were said to hold the highest position in divine society, including the solar deity Ra, the mysterious god Amun, and the mother goddess Isis. The highest deity was usually credited with the creation of the world and often connected with the life-giving power of the sun. Some scholars have argued, based in part on Egyptian writings, that the Egyptians came to recognize a single divine power that lay behind all things and was present in all the other deities. Yet they never abandoned their original polytheistic view of the world, except possibly during the era of Atenism in the 14th century BC, when official religion focused exclusively on an abstract solar deity, the Aten.

Gods were assumed to be present throughout the world, capable of influencing natural events and the course of human lives. People interacted with them in temples and unofficial shrines, for personal reasons as well as for larger goals of state rites. Egyptians prayed for divine help, used rituals to compel deities to act, and called upon them for advice. Humans' relations with their gods were a fundamental part of Egyptian society.

Egyptian writings describe the gods' bodies in detail. They are made of precious materials; their flesh is gold, their bones are silver, and their hair is lapis lazuli. They give off a scent that the Egyptians likened to the incense used in rituals. Some texts give precise descriptions of particular deities, including their height and eye color. Yet these characteristics are not fixed; in myths, gods change their appearances to suit their own purposes.[151] Egyptian texts often refer to deities' true, underlying forms as "mysterious". The Egyptians' visual representations of their gods are therefore not literal. They symbolize specific aspects of each deity's character, functioning much like the ideograms in hieroglyphic writing.[152] For this reason, the funerary god Anubis is commonly shown in Egyptian art as a dog or jackal, a creature whose scavenging habits threaten the preservation of buried mummies, in an effort to counter this threat and employ it for protection. His black coloring alludes to the color of mummified flesh and to the fertile black soil that Egyptians saw as a symbol of resurrection.[153]

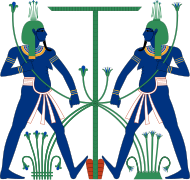

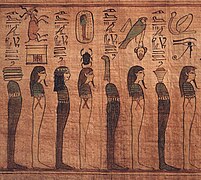

Most deities were depicted in several ways. Hathor could be a cow, cobra, lioness, or a woman with bovine horns or ears. By depicting a given god in different ways, the Egyptians expressed different aspects of its essential nature.[152] The gods are depicted in a finite number of these symbolic forms, so they can often be distinguished from one another by their iconographies. These forms include men and women (anthropomorphism), animals (zoomorphism), and, more rarely, inanimate objects. Combinations of forms, such as deities with human bodies and animal heads, are common.[7] New forms and increasingly complex combinations arose in the course of history,[143] with the most surreal forms often found among the demons of the underworld.[155] Some gods can only be distinguished from others if they are labeled in writing, as with Isis and Hathor.[156] Because of the close connection between these goddesses, they could both wear the cow-horn headdress that was originally Hathor's alone.[157]

Certain features of divine images are more useful than others in determining a god's identity. The head of a given divine image is particularly significant.[158] In a hybrid image, the head represents the original form of the being depicted, so that, as the Egyptologist Henry Fischer put it, "a lion-headed goddess is a lion-goddess in human form, while a royal sphinx, conversely, is a man who has assumed the form of a lion."[159] Divine headdresses, which range from the same types of crowns used by human kings to large hieroglyphs worn on gods' heads, are another important indicator. In contrast, the objects held in gods' hands tend to be generic.[158] Male deities hold was staffs, goddesses hold stalks of papyrus, and both sexes carry ankh signs, representing the Egyptian word for "life", to symbolize their life-giving power.[160]

The forms in which the gods are shown, although diverse, are limited in many ways. Many creatures that are widespread in Egypt were never used in divine iconography. Others could represent many deities, often because these deities had major characteristics in common.[161] Bulls and rams were associated with virility, cows and falcons with the sky, hippopotami with maternal protection, felines with the sun god, and serpents with both danger and renewal.[162][163] Animals that were absent from Egypt in the early stages of its history were not used as divine images. For instance, the horse, which was only introduced in the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1650–1550 BC), never represented a god. Similarly, the clothes worn by anthropomorphic deities in most periods changed little from the styles used in the Old Kingdom: a kilt, false beard, and often a shirt for male gods and a long, tight-fitting dress for goddesses.[161][Note 4]

The basic anthropomorphic form varies. Child gods are depicted nude, as are some adult gods when their procreative powers are emphasized.[165] Certain male deities are given heavy bellies and breasts, signifying either androgyny or prosperity and abundance.[166] Whereas most male gods have red skin and most goddesses are yellow—the same colors used to depict Egyptian men and women—some are given unusual, symbolic skin colors.[167] Thus, the blue skin and paunchy figure of the god Hapi alludes to the Nile flood he represents and the nourishing fertility it brought.[168] A few deities, such as Osiris, Ptah, and Min, have a "mummiform" appearance, with their limbs tightly swathed in cloth.[169] Although these gods resemble mummies, the earliest examples predate the cloth-wrapped style of mummification, and this form may instead hark back to the earliest, limbless depictions of deities.[170]

Some inanimate objects that represent deities are drawn from nature, such as trees or the disk-like emblems for the sun and the moon.[171] Some objects associated with a specific god, like the crossed bows representing Neith (𓋋) or the emblem of Min (𓋉) symbolized the cults of those deities in Predynastic times.[172] In many of these cases, the nature of the original object is mysterious.[173] In the Predynastic and Early Dynastic Periods, gods were often represented by divine standards: poles topped by emblems of deities, including both animal forms and inanimate objects.[174]

![Statue of the crocodile god Sobek in fully animal form, possibly a cult image from a temple.[175] Nineteenth or twentieth century BC.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/ff/Krokodilsstatue.jpg/300px-Krokodilsstatue.jpg)