Art of ancient Egypt

Ancient Egyptian art refers to art produced in ancient Egypt between the 6th millennium BC and the 4th century AD, spanning from Prehistoric Egypt until the Christianization of Roman Egypt. It includes paintings, sculptures, drawings on papyrus, faience, jewelry, ivories, architecture, and other art media. It was a conservative tradition whose style changed very little over time. Much of the surviving examples comes from tombs and monuments, giving insight into the ancient Egyptian afterlife beliefs.

"Egyptian art" redirects here. For the art of modern Egypt, see Contemporary art in Egypt.The ancient Egyptian language had no word for "art". Artworks served an essentially functional purpose that was bound with religion and ideology. To render a subject in art was to give it permanence. Therefore, ancient Egyptian art portrayed an idealized, unrealistic view of the world. There was no significant tradition of individual artistic expression since art served a wider and cosmic purpose of maintaining order (Ma'at).

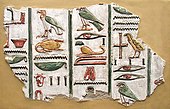

Not all Egyptian reliefs were painted, and less-prestigious works in tombs, temples and palaces were merely painted on a flat surface. Stone surfaces were prepared by whitewash, or if rough, a layer of coarse mud plaster, with a smoother gesso layer above; some finer limestones could take paint directly. Pigments were mostly mineral, chosen to withstand strong sunlight without fading. The binding medium used in painting remains unclear: egg tempera and various gums and resins have been suggested. It is clear that true fresco, painted into a thin layer of wet plaster, was not used. Instead, the paint was applied to dried plaster, in what is called fresco a secco in Italian. After painting, a varnish or resin was usually applied as a protective coating, and many paintings with some exposure to the elements have survived remarkably well, although those on fully exposed walls rarely have.[106] Small objects including wooden statuettes were often painted using similar techniques.

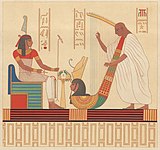

Many ancient Egyptian paintings have survived in tombs, and sometimes temples, due to Egypt's extremely dry climate. The paintings were often made with the intent of making a pleasant afterlife for the deceased. The themes included journeys through the afterworld or protective deities introducing the deceased to the gods of the underworld (such as Osiris). Some tomb paintings show activities that the deceased were involved in when they were alive and wished to carry on doing for eternity.

From the New Kingdom period and afterwards, the Book of the Dead was buried with the entombed person. It was considered important for an introduction to the afterlife.[107]

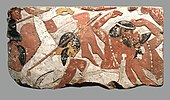

Egyptian paintings are painted in such a way to show a side view and a front view of the animal or person at the same time. For example, the painting to the right shows the head from a profile view and the body from a frontal view. Their main colors were red, blue, green, gold, black and yellow.

Paintings showing scenes of hunting and fishing can have lively close-up landscape backgrounds of reeds and water, but in general Egyptian painting did not develop a sense of depth, and neither landscapes nor a sense of visual perspective are found, the figures rather varying in size with their importance rather than their location.

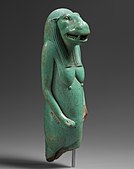

Ancient Egyptian architects used sun-dried and kiln-baked bricks, fine sandstone, limestone and granite. Architects carefully planned all their work. The stones had to fit precisely together, since no mud or mortar was used. When creating the pyramids it is unknown how the workers or stones reached the top of them as no records were kept of their construction. When the top of the structure was completed, the artists decorated from the top down, removing ramp sand as they went down. Exterior walls of structures like the pyramids contained only a few small openings. Hieroglyphic and pictorial carvings in brilliant colors were abundantly used to decorate Egyptian structures, including many motifs, like the scarab, sacred beetle, the solar disk, and the vulture. They described the changes the Pharaoh would go through to become a god.[109]

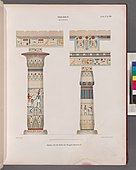

As early as 2600 BC the architect Imhotep made use of stone columns whose surface was carved to reflect the organic form of bundled reeds, like papyrus, lotus and palm; in later Egyptian architecture faceted cylinders were also common. Their form is thought to derive from archaic reed-built shrines. Carved from stone, the columns were highly decorated with carved and painted hieroglyphs, texts, ritual imagery and natural motifs. One of the most important types are the papyriform columns. The origin of these columns goes back to the 5th Dynasty. They are composed of lotus (papyrus) stems which are drawn together into a bundle decorated with bands: the capital, instead of opening out into the shape of a bellflower, swells out and then narrows again like a flower in bud. The base, which tapers to take the shape of a half-sphere like the stem of the lotus, has a continuously recurring decoration of stipules. At the Luxor Temple, the columns are reminiscent of papyrus bundles, perhaps symbolic of the marsh from which the ancient Egyptians believed the creation of the world to have unfolded.

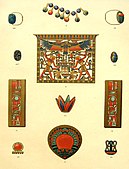

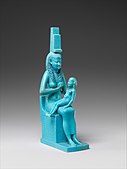

The ancient Egyptians exhibited a love of ornament and personal decoration from earliest Predynastic times. Badarian burials often contained strings of beads made from glazed steatite, shell and ivory. Jewelry in gold, silver, copper and faience is also attested in the early Predynastic period; more varied materials were introduced in the centuries preceding the 1st Dynasty. By the Old Kingdom, the combination of carnelian, turquoise and lapis lazuli had been established for royal jewelry, and this was to become standard in the Middle Kingdom. Less sophisticated pieces might use bone, mother-of-pearl or cowrie shells.

The particular choice of materials depended upon practical, aesthetical and symbolic considerations. Some types of jewelry remained perennially popular, while others went in and out of fashion. In the first category were bead necklaces, bracelets, armlets and girdles. Bead aprons are first attested in the 1st Dynasty, while usekh broad collars became a standard type from the early Old Kingdom. In the Middle Kingdom, they had fallen from favor, to be replaced by finger-rings and ear ornaments (rings and plugs). New Kingdom jewelry is generally more elaborate and garish than that of earlier periods, and was influenced by styles from the Ancient Greece and the Levant. Many fine examples were found in the tomb of Tutankhamun. Jewelry, both royal and private, was replete with religious symbolism. It was also used to display the wealth and rank of the wearer. Royal jewels were always the most elaborate, as exemplified by the pieces found at Dahshur and Lahun, made for princesses of the 18th Dynasty, favored courtiers were rewarded with the "gold of honor" as a sign of royal favor.

The techniques of jewelry-making can be reconstructed from surviving artifacts and from tomb decoration. A jeweler's workshop is shown in the tomb of Mereruka; several New Kingdom tombs at Thebes contain similar scenes.[110]

Different types of pottery items were deposited in tombs of the dead. Some such pottery items represented interior parts of the body, such as the lungs, the liver and smaller intestines, which were removed before embalming. A large number of smaller objects in enamel pottery were also deposited with the dead. It was customary for the tomb walls to be crafted with cones of pottery, about 15 to 25 cm (6 to 10 in) tall, on which were engraved or impressed legends relating to the dead occupants of the tombs. These cones usually contained the names of the deceased, their titles, offices which they held, and some expressions appropriate to funeral purposes.

Egyptian writing remained a remarkably conservative system, and the preserve of a tiny literate minority, while the spoken language underwent considerable change. Egyptian stelas are decorated with finely carved hieroglyphs.

The use of hieroglyphic writing arose from proto-literate symbol systems in the Early Bronze Age, around the 32nd century BC (Naqada III), with the first decipherable sentence written in the Egyptian language dating to the Second Dynasty (28th century BC). Egyptian hieroglyphs developed into a mature writing system used for monumental inscription in the classical language of the Middle Kingdom period; during this period, the system made use of about 900 distinct signs. The use of this writing system continued through the New Kingdom and Late Period, and on into the Persian and Ptolemaic periods. Late use of hieroglyphics are found in the Roman period, extending into the 4th century AD.

Although, by modern standards, ancient Egyptian houses would have been very sparsely furnished, woodworking and cabinet-making were highly developed crafts. All the main types of furniture are attested, either as surviving examples or in tomb decoration. Chairs were only for the wealthy; most people would have used low stools. Beds consisted of a wooden frame, with matting or leather webbing to provide support; the most elaborate beds also had a canopy, hung with netting, to provide extra privacy and protection from insects. The feet of chairs, stools and beds were often modeled to resemble bull hooves or, in later periods, lion feet or duck heads. Wooden furniture was often coated with a layer of plaster and painted.

Royal furniture was more elaborate, making use of inlays, veneers and marquetry. Funerary objects from the tomb of Tutankhamun include tables, boxes and chests, a gilded throne, and ritual beds shaped like elongated hippos and cattle. The burial equipment of Hetepheres included a set of travelling furniture, light and easy to dismantle. Such furniture must have been used on military campaigns and other royal journeys.[113] Egyptian furniture has highly influenced the development of Greco-Roman furniture. It also was one of the principal sources of inspiration of a style known as Empire.[114] The main motifs used are: palm and lotus leaves, flowers, lion heads and claws, bull hooves, bird heads, and geometric combinations. Everything is sober and with a monumental character.[115]

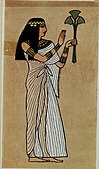

Artistic representations, supplemented by surviving garments, are the main sources of evidence for ancient Egyptian fashion. The two sources are not always in agreement, however, and it seems that representations were more concerned with highlighting certain attributes of the person depicted than with accurately recordings their true appearance. For example, women were often shown with restrictive, tight-fitting dresses, perhaps to emphasize their figures.

As in most societies, fashions in Egypt changed over time; different clothes were worn in different seasons of the year, and by different sections of society. Particular office-holders, especially priests and the king, had their own special garments.

For the general population, clothing was simple, predominantly of linen, and probably white or off-white in color. It would have shown the dirt easily, and professional launderers are known to have been attached to the New Kingdom workmen's village at Deir el-Medina. Men would have worn a simple loin-cloth or short kilt (known as shendyt), supplemented in winter by a heavier tunic. High-status individuals could express their status through their clothing, and were more susceptible to changes in fashion.

Longer, more voluminous clothing made an appearance in the Middle Kingdom; flowing, elaborately pleated, diaphanous robes for men and women were particularly popular in the late 18th Dynasty and the Ramesside period. Decorated textiles also became more common in the New Kingdom. In all periods, women's dresses may have been enhanced by colorful bead netting worn over the top. In the Roman Period, Egypt became known for the manufacture of fine clothing. Coiled sewn sandals or sandals of leather are the most commonly attested types of footwear. Examples of these, together with linen shirts and other clothing, were discovered in the tomb of Tutankhamun.[116]

Use of makeup, especially around the eyes, was a characteristic feature of ancient Egyptian culture from Predynastic times. Black kohl (eye-paint) was applied to protect the eyes, as well as for aesthetic reasons. It was usually made of galena, giving a silvery-black color; during the Old Kingdom, green eye-paint was also used, made from malachite. Egyptian women painted their lips and cheeks, using rouge made from red ochre. Henna was applied as a dye for hair, fingernails and toenails, and perhaps also nipples. Creams and unguents to condition the skin were popular, and were made from various plant extracts.[117]

Ancient Egypt shared a long and complex history with the Nile Valley to the south, the region called Nubia (modern Sudan). Beginning with the Kerma culture and continuing with the Kingdom of Kush based at Napata and then Meroë, Nubian culture absorbed Egyptian influences at various times, for both political and religious reasons. The result is a rich and complex visual culture.

The artistic production of Meroë reflects a range of influences. First, it was an indigenous African culture with roots stretching back thousands of years. To this is added the fact that the wealth of Meroë was based on trade with Egypt when it was ruled by the Ptolemaic dynasty (332–330 BC) and the Romans (30 BC – 395 AD), so Hellenistic and Roman objects and ideas were imported, as well as Egyptian influences.

Egyptian Revival art is a style in Western art, mainly of the early nineteenth century, in which Egyptian motifs were applied to a wide variety of decorative arts objects. It was underground in American decorative arts throughout the nineteenth century, continuing into the 1920s. The major motifs of Egyptian art, such as obelisks, hieroglyphs, the sphinx, and pyramids, were used in various artistic media, including architecture, furniture, ceramics, and silver. Egyptian motifs provided an exotic alternative to the more traditional styles of the day. Over the course of the nineteenth century, American tastes evolved from a highly ornamented aesthetic to a simpler, sparer sense of decoration; the vocabulary of ancient Egyptian art would be interpreted and adapted in different ways depending on the standards and motivations of the time.[124]

Enthusiasm for the artistic style of Ancient Egypt is generally attributed to the excitement over Napoleon's conquest of Egypt and, in Britain, to Admiral Nelson's defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of the Nile in 1798. Napoleon took a scientific expedition with him to Egypt. Publication of the expedition's work, the Description de l'Égypte, began in 1809 and came out in a series though 1826, inspiring everything from sofas with sphinxes for legs, to tea sets painted with the pyramids. It was the popularity of the style that was new, Egyptianizing works of art had appeared in scattered European settings from the time of the Renaissance.

Further reading[edit]

Hill, Marsha (2007). Gifts for the gods: images from Egyptian temples. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9781588392312.

![Tag depicting king Den; c. 3000 BC; ivory; 4.5 × 5.3 cm; from Abydos (Egypt); British Museum (London)[21]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b3/MacGregor_Plate_%28with_background%29.jpg/170px-MacGregor_Plate_%28with_background%29.jpg)

![Amenhotep III; 1390–1352 BC; quartzite; height: 2.49 m; Luxor Museum (Luxor, Egypt)[102]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9f/Luxor_Museum_Amenophis_III._Statue_05.jpg/115px-Luxor_Museum_Amenophis_III._Statue_05.jpg)