Anglo-Japanese Alliance

The first Anglo-Japanese Alliance (日英同盟, Nichi-Ei Dōmei) was an alliance between Britain and Japan. It was in operation from 1902 to 1922. The original British goal was to prevent Russia from expanding in Manchuria while also preserving the territorial integrity of China and Korea. For the British, it marked the end of a period of "splendid isolation" while allowing for greater focus on protecting India and competing in the Anglo-German naval arms race. The alliance was part of a larger British strategy to reduce imperial overcommitment and recall the Royal Navy to defend Britain. The Japanese, on the other hand, gained international prestige from the alliance and used it as a foundation for their diplomacy for two decades. In 1905, the treaty was redefined in favor of Japan concerning Korea. It was renewed in 1911 for another ten years and replaced by the Four-Power Treaty in 1922.[1]

"Anglo-Japanese Treaty" redirects here. For other uses, see Anglo-Japanese (disambiguation).Type

Mutual defence in the event of open war with another nation

30 January 1902

31 January 1902

1923

Lord Lansdowne, United Kingdom

Lord Lansdowne, United Kingdom Count Hayashi Tadasu, Japan

Count Hayashi Tadasu, Japan

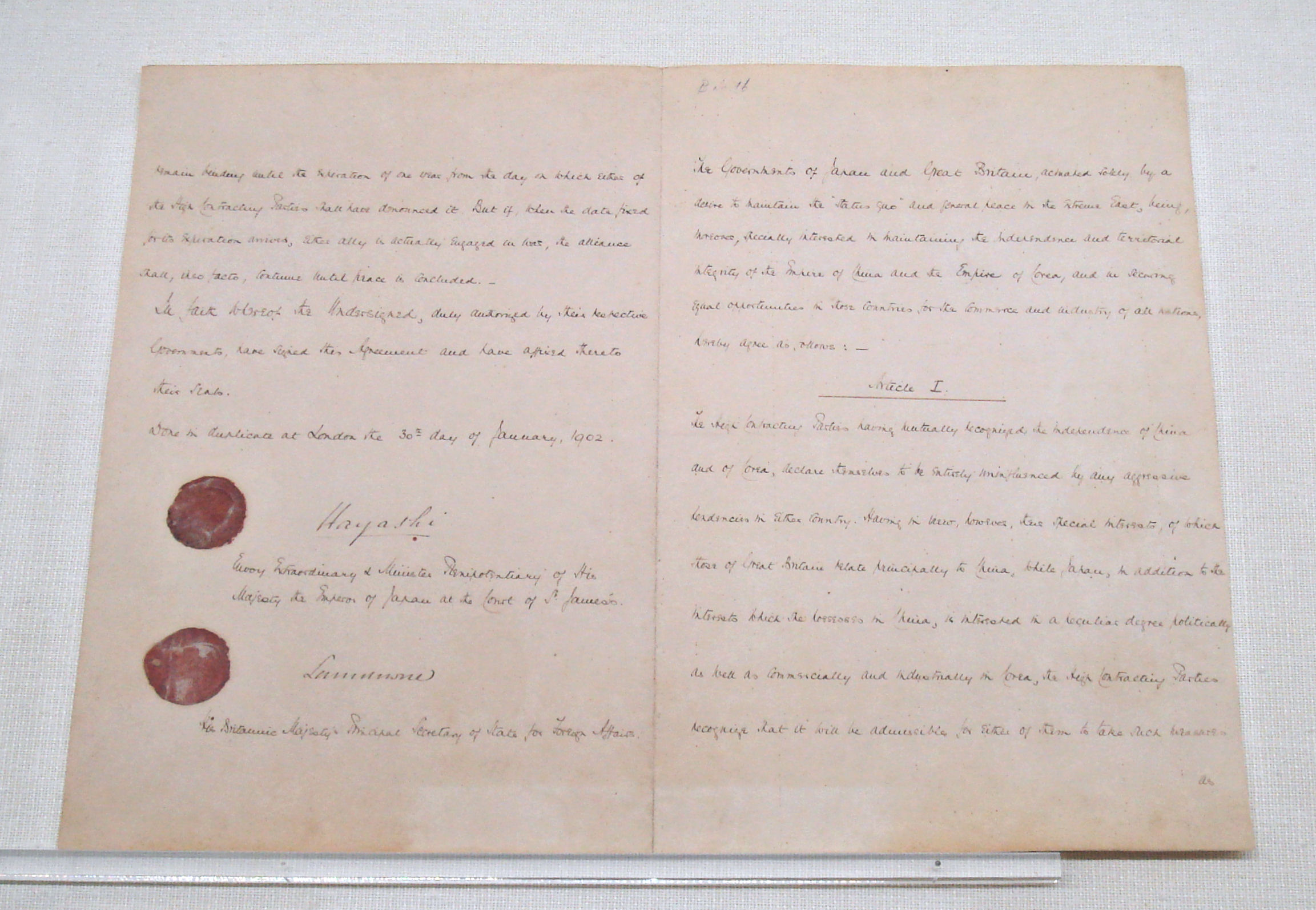

The alliance was signed in London at Lansdowne House on 30 January 1902 by Lord Lansdowne, British Foreign Secretary, and Hayashi Tadasu, Japanese diplomat.[2]

The Anglo-Japanese alliance was renewed and expanded in scope twice, in 1905 and 1911, playing a major role in World War I before the alliance's demise in 1921 and termination in 1923.[3][4][5]

The main threat for both sides was from Russia. France was concerned about war with Britain and, in cooperation with Britain, abandoned its ally, Russia, to avoid blame for the Russo-Japanese War of 1904. France supported Russia economically against Japan anyway. However, Britain siding with Japan angered the United States and some British dominions, whose opinion of the Empire of Japan worsened and gradually became hostile.[6]

The treaty contained six articles:

Article 1

Article 2

Article 3

Article 4

Article 5

Article 6

Articles 2 and 3 were most crucial concerning war and mutual defense.

The treaty laid out an acknowledgment of Japanese interests in Korea without obligating Britain to help if a conflict arose where Japan only had one adversary. Japan was likewise not obligated to defend British interests unless there were two adversaries.

Although written using careful and clear language, the two sides understood the Treaty slightly differently. Britain saw it as a gentle warning to Russia, while Japan was emboldened by it. From that point on, even those of a moderate stance refused to accept a compromise over the issue of Korea. Extremists saw it as an open invitation for imperial expansion.

Limitations[edit]

Despite the ostensibly friendly relations between Britain and Japan during the early 20th century, the relationship started to strain over various issues. One such strain was the issue of the "racial equality clause" as proposed by the Japanese delegation at the Paris Peace Conference. The clause, which was to be attached to the Covenant of the League of Nations, was compatible with the British stance of equality for all subjects as a principle for maintaining imperial unity; however, there were significant deviations in the stated interests of Britain's dominions, notably Australia, and the British delegation ultimately acceded to imperial opposition and declined to support the clause.[26]

Another strain was the Twenty-One Demands issued by Japan to the Republic of China in 1915. The demands would have drastically increased Japanese influence in China and transformed the Chinese state into a de facto protectorate of Japan. Feeling desperate, the Chinese government appealed to Britain and the U.S., which forced Japan to moderate the demands issued; ultimately, the Japanese government gained little influence in China, but lost prestige amongst the Western nations (including Britain, which was affronted and no longer trusted the Japanese as a reliable ally).[27]

Even though Britain was the wealthiest industrialized power, and Japan was a newly industrialized power with a large export market, which would seem to create natural economic ties, those ties were somewhat limited,[23] which provided a major limitation of the alliance. British banks saw Japan as a risky investment due to what they saw as restrictive property laws and an unstable financial situation, and offered loans to Japan with high interest rates, similar to those they offered the Ottoman Empire, Chile, China, and Egypt, which was disappointing to Japan. The banker and later Prime Minister Takahashi Korekiyo argued that Britain was implying, through unattractive loan terms, that Japan had reverted from one of the "civilized nations" to "undeveloped nations", referring that Japan had more easily received foreign capital to fund its First Sino-Japanese War than the Russo-Japanese War.[23] Nathaniel Rothschild was initially skeptical of Japan's economy; however, he would later describe Osaka as the "Manchester of Japan" and Japan as "one of the countries of the future."[23] Henry Dyer wrote after 1906 that Japanese bonds "has aroused keen interest among British investors, who have always been partial to Japanese bonds." Dyer, a recipient of the Order of the Rising Sun from Emperor Meiji, had played a role in the expansion of industrialization and engineering in Japan as part of a significant foreign investment. Dyer criticized what he saw as widespread British skepticism of Japan's economy.[23] Meanwhile, influential industrialists in Japan such as businessman Iwasaki Yanosuke were at times skeptical of foreign investment, which led the Japanese government to channel it through some controlled enterprises acting as intermediaries with the private sector in London and Tokyo, which was seen as excess regulation by some British industrialists.[23] Nevertheless, Britain did lend capital to Japan during the Russo-Japanese War,[20] while Japan provided major loans to the Entente during World War I.