Anne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson (née Marbury; July 1591 – August 1643) was a Puritan spiritual advisor, religious reformer, and an important participant in the Antinomian Controversy which shook the infant Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. Her strong religious convictions were at odds with the established Puritan clergy in the Boston area and her popularity and charisma helped create a theological schism that threatened the Puritan religious community in New England. She was eventually tried and convicted, then banished from the colony with many of her supporters.

For the British lawyer, see Anne-Marie Hutchinson.

Anne Hutchinson

August 1643 (aged 52)

Killed by Siwanoys during Kieft's War

Home schooled and self-taught

Role in the Antinomian Controversy

- Francis Marbury (father)

- Bridget Dryden (mother)

- Governor Peleg Sanford

- Great great grandmother of Governor Thomas Hutchinson

- Ancestor of U.S. presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt, George H. W. Bush, and George W. Bush

- Ancestor of U.S. Politicians Mitt Romney, Jon Huntsman, Jr.

Hutchinson was born in Alford, Lincolnshire, England, the daughter of Francis Marbury, an Anglican cleric and school teacher who gave her a far better education than most other girls received. She lived in London as a young adult, and there married a friend from home, William Hutchinson. The couple moved back to Alford where they began following preacher John Cotton in the nearby port of Boston, Lincolnshire. Cotton was compelled to emigrate in 1633, and the Hutchinsons followed a year later with their 15 children and soon became well established in the growing settlement of Boston in New England. Hutchinson was a midwife and helpful to those needing her assistance, as well as forthcoming with her personal religious understandings. Soon she was hosting women at her house weekly, providing commentary on recent sermons. These meetings became so popular that she began offering meetings for men as well, including the young governor of the colony, Henry Vane.

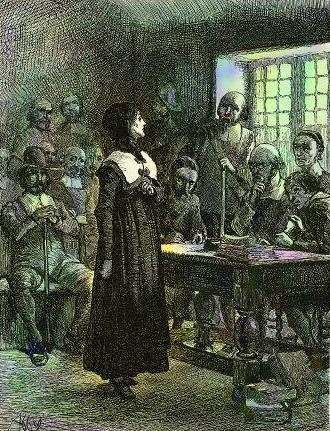

Hutchinson began to accuse the local ministers (except for Cotton and her husband's brother-in-law, John Wheelwright) of preaching a covenant of works rather than a covenant of grace, and many ministers began to complain about her increasingly blatant accusations, as well as certain unorthodox theological teachings. The situation eventually erupted into what is commonly called the Antinomian Controversy, culminating in her 1637 trial, conviction, and banishment from the colony. The main thrust of the evidence was her contemptuous remarks about the Puritan ministers, but the court refused to state the basis of her conviction. This was followed by a March 1638 church trial in which she was put out of her congregation.

Hutchinson and many of her supporters established the settlement of Portsmouth, Rhode Island with encouragement from Providence Plantations founder Roger Williams in what became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. After her husband's death a few years later, threats of Massachusetts annexing Rhode Island compelled Hutchinson to move totally outside the reach of Boston into the lands of the Dutch. Five of her older surviving children remained in New England or in England, while she settled with her younger children near an ancient landmark, Split Rock, in what later became The Bronx in New York City. Tensions were high at the time with the Siwanoy Indian tribe. In August 1643, Hutchinson, six of her children, and other household members were killed by Siwanoys during Kieft's War. The only survivor was her nine-year-old daughter Susanna, who was taken captive.

Hutchinson is a key figure in the history of religious freedom in England's American colonies and the history of women in ministry, challenging the authority of the ministers. She is honored by Massachusetts with a State House monument calling her a "courageous exponent of civil liberty and religious toleration".[1] Historian Michael Winship, author of two books about her, has called her "the most famous—or infamous—English woman in colonial American history".[2]

Historical impact[edit]

Hutchinson claimed that she was a prophetess, receiving direct revelation from God. In this capacity, she prophesied during her trial that God would send judgment upon the Massachusetts Bay Colony and would wipe it from existence.[124] She further taught her followers that personal revelation from God was as authoritative in a person's life as the Bible, a teaching that was antithetical to Puritan theology. She also claimed that she could identify "the elect" among the colonists.[125] These positions ultimately caused John Cotton, John Winthrop, and other former friends to view her as an antinomian heretic.[125]

According to modern historian Michael Winship, Hutchinson is famous, not so much for what she did or said during the Antinomian Controversy, but for what John Winthrop made of her in his journal and in his account of the controversy called the Short Story. According to Winship, Hutchinson became the reason in Winthrop's mind for all of the difficulties the colony had experienced, though unfairly, and with her departure, any other lingering issues were swept under the carpet.[126] Winthrop's account has given Hutchinson near legendary status and, as with all legends, what she stood for has shifted over the centuries.[126] Winthrop described her as "a woman of ready wit and bold spirit".[127] In the words of Winship, to Winthrop, Hutchinson was a "hell-spawned agent of destructive anarchy".[126] The close relationship between church and state in Massachusetts Bay meant that a challenge to the ministers was interpreted as challenge to established authority of all kinds.[127] To 19th century America, she was a crusader for religious liberty, as the nation celebrated its new achievement of the separation of church and state. Finally, in the 20th century, she became a feminist leader, credited with terrifying the patriarchs, not because of her religious views but because she was an assertive woman.[126] According to feminist Amy Lang, Hutchinson failed to understand that "the force of the female heretic vastly exceeds her heresy".[128] Lang argues that it was difficult for the court to pin a crime on her; her true crime in their eyes, according to Lang's interpretation, was the violation of her role in Puritan society, and she was condemned for undertaking the roles of teacher, minister, magistrate, and husband.[128] (However, the Puritans themselves stated that the threat which they perceived was entirely theological, and no direct mention was ever made to indicate that they were threatened by her gender.)[129]

Winship calls Hutchinson "a prophet, spiritual adviser, mother of fifteen, and important participant in a fierce religious controversy that shook the infant Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638",[2] upheld as a symbol of religious freedom, liberal thinking, and Christian feminism. Anne Hutchinson is a contentious figure, having been lionised, mythologised, and demonised by various writers. In particular, historians and other observers have interpreted and re-interpreted her life within the following frameworks: the status of women, power struggles within the Church, and a similar struggle within the secular political structure. As to her overall historical impact, Winship writes, "Hutchinson's well-publicized trials and the attendant accusations against her made her the most famous, or infamous, English woman in colonial American history."[2]

Family[edit]

Immediate family[edit]

Anne and William Hutchinson had 15 children, all of them born and baptised in Alford except for the last child, who was baptised in Boston, Massachusetts.[149] Of the 14 children born in England, 11 lived to sail to New England.[149]