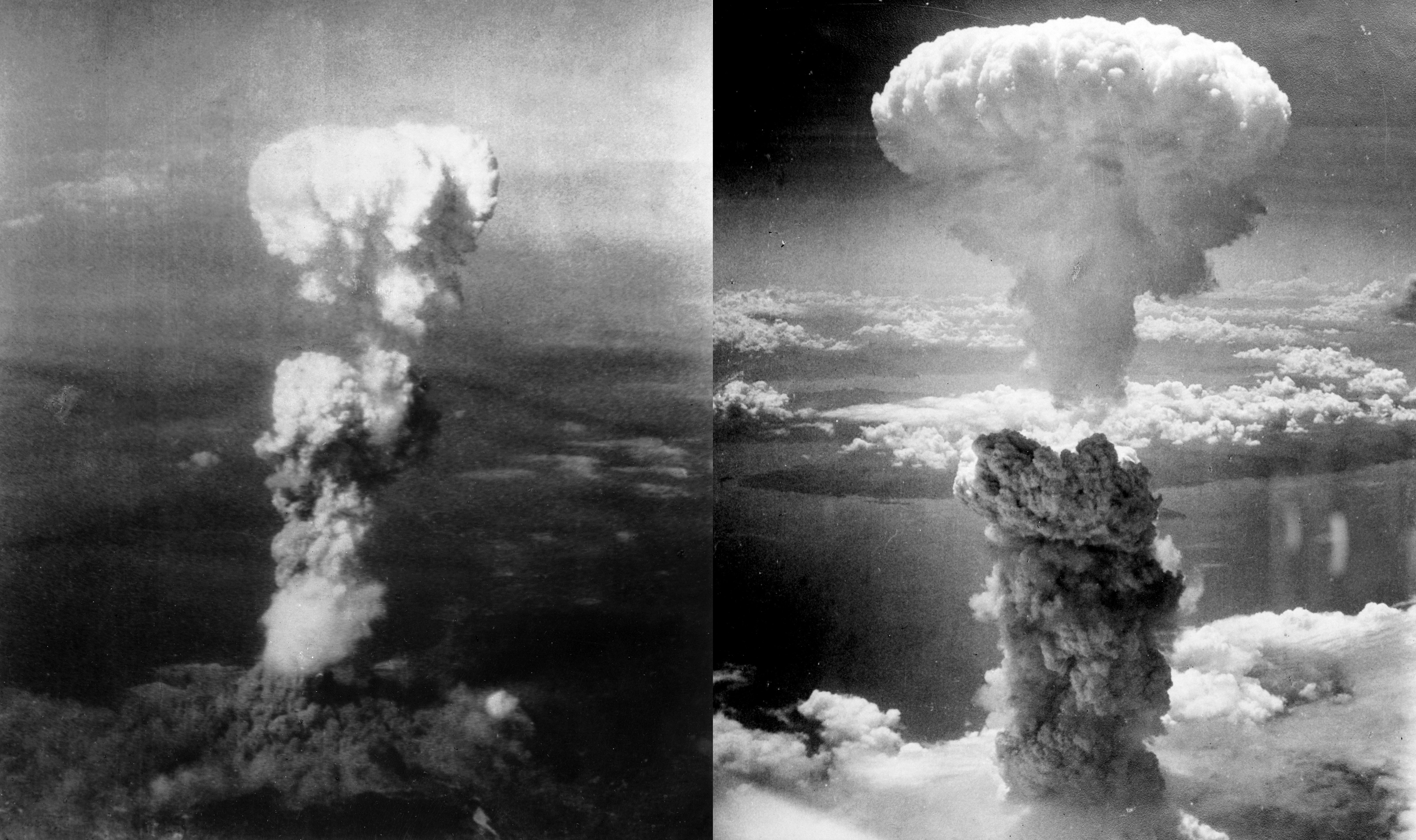

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

On 6 and 9 August 1945, the United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the only use of nuclear weapons in an armed conflict. Japan surrendered to the Allies on 15 August, six days after the bombing of Nagasaki and the Soviet Union's declaration of war against Japan and invasion of Japanese-occupied Manchuria. The Japanese government signed the instrument of surrender on 2 September, effectively ending the war.

Operation Centerboard

6 August 1945

9 August 1945

- Manhattan Project

- 509th Composite Group: 1,770 U.S.

- 70,000–126,000 civilians killed

- 7,000–20,000 soldiers killed

- 12 Allied prisoners of war

- 60,000–80,000 killed (within 4 months)

- 150+ soldiers killed

- 8–13 Allied prisoners of war

- 129,000–226,000

In the final year of World War II, the Allies prepared for a costly invasion of the Japanese mainland. This undertaking was preceded by a conventional bombing and firebombing campaign that devastated 64 Japanese cities. The war in the European theatre concluded when Germany surrendered on 8 May 1945, and the Allies turned their full attention to the Pacific War. By July 1945, the Allies' Manhattan Project had produced two types of atomic bombs: "Little Boy", an enriched uranium gun-type fission weapon, and "Fat Man", a plutonium implosion-type nuclear weapon. The 509th Composite Group of the United States Army Air Forces was trained and equipped with the specialized Silverplate version of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress, and deployed to Tinian in the Mariana Islands. The Allies called for the unconditional surrender of the Imperial Japanese armed forces in the Potsdam Declaration on 26 July 1945, the alternative being "prompt and utter destruction". The Japanese government ignored the ultimatum.

The consent of the United Kingdom was obtained for the bombing, as was required by the Quebec Agreement, and orders were issued on 25 July by General Thomas Handy, the acting chief of staff of the United States Army, for atomic bombs to be used against Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata, and Nagasaki. These targets were chosen because they were large urban areas that also held militarily significant facilities. On 6 August, a Little Boy was dropped on Hiroshima. Three days later, a Fat Man was dropped on Nagasaki. Over the next two to four months, the effects of the atomic bombings killed 90,000 to 146,000 people in Hiroshima and 60,000 to 80,000 people in Nagasaki; roughly half occurred on the first day. For months afterward, many people continued to die from the effects of burns, radiation sickness, and other injuries, compounded by illness and malnutrition. Though Hiroshima had a sizable military garrison, most of the dead were civilians.

Scholars have extensively studied the effects of the bombings on the social and political character of subsequent world history and popular culture, and there is still much debate concerning the ethical and legal justification for the bombings. Supporters state that the atomic bombings were necessary to bring an end to the war with minimal casualties and ultimately prevented a greater loss of life; critics state that the bombings were unnecessary for the war's end and a war crime, highlighting the moral and ethical implications of an intentional nuclear attack on civilians.

Memorials

Hiroshima

Hiroshima was subsequently struck by Typhoon Ida on 17 September 1945. More than half the bridges were destroyed, and the roads and railroads were damaged, further devastating the city.[315] The population increased from 83,000 soon after the bombing to 146,000 in February 1946.[316] The city was rebuilt after the war, with help from the national government through the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law passed in 1949. It provided financial assistance for reconstruction, along with land donated that was previously owned by the national government and used for military purposes.[317] In 1949, a design was selected for the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, the closest surviving building to the location of the bomb's detonation, was designated the Hiroshima Peace Memorial. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum was opened in 1955 in the Peace Park.[318] Hiroshima also contains a Peace Pagoda, built in 1966 by Nipponzan-Myōhōji.[319]

On January 27, 1981, the Atomic Bombing Relic Selecting Committee of Hiroshima announced to build commemorative plaques at nine historical sites related to the bombing in the year. Genbaku Dome, Shima Hospital (hypocenter), Motoyasu Bridge all unveiled plaques with historical photographs and descriptions. The rest sites planned including Hondō Shopping Street, Motomachi No.2 Army Hospital site, Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital, Fukuromachi Elementary School, Hiroshima City Hall and Hiroshima Station. The committee also planned to establish 30 commemorative plaques in three years.[320]