Black Loyalist

Black Loyalists were people of African descent who sided with the Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War.[1] In particular, the term refers to men who escaped enslavement by Patriot masters and served on the Loyalist side because of the Crown's guarantee of freedom.

Black Loyalist

1775–1784

British provincial units, Loyalist militias, associators

infantry, dragoons (mounted infantry), irregular, labor duty

companies-regiments

Both White British military officers and Black Loyalist officers

Some 3,000 Black Loyalists were evacuated from New York to Nova Scotia; they were individually listed in the Book of Negroes as the British gave them certificates of freedom and arranged for their transportation.[2] The Crown gave them land grants and supplies to help them resettle in Nova Scotia. Some of the European Loyalists who emigrated to Nova Scotia brought their enslaved servants with them, making for an uneasy society. One historian has argued that those slaves should not be regarded as Loyalists, as they had no choice in their fates.[3] Other Black Loyalists were evacuated to London or the Caribbean colonies.

Thousands of enslaved people escaped from plantations and fled to British lines, especially after British occupation of Charleston, South Carolina. When the British evacuated, they took many former enslaved people with them. Many ended up among London's Black Poor, with 4,000 resettled by the Sierra Leone Company to Freetown in Africa in 1787. Five years later, another 1,192 Black Loyalists from Nova Scotia chose to emigrate to Sierra Leone, becoming known as the Nova Scotian Settlers in the new British colony of Sierra Leone. Both waves of settlers became part of the Sierra Leone Creole people and the founders of the nation of Sierra Leone. Thomas Jefferson referred to the Black Loyalists as "the fugitives from these States".[4]

Background[edit]

Slavery in England had never been authorized by legal statutes. Villeinage, a form of semi-serfdom, was legally recognized but long obsolete. In 1772, a slave threatened with being taken out of England and returned to the Caribbean challenged the authority of his master in the case of Somerset v Stewart. The Chief Justice, Lord Mansfield, ruled that slavery had no standing under common law and slave owners, therefore, were not permitted to transport slaves outside England and Wales against their will. Many observers took it to mean that slavery was ended in England.

Lower courts often interpreted the ruling as determining that the status of slavery did not exist in England and Wales, but Mansfield ruled more narrowly. The decision did not apply to the North American and Caribbean colonies, where local legislatures had passed laws to institutionalize slavery. A number of cases were presented to the English courts for the emancipation of slaves residing in England, and numerous American runaways hoped to reach England where they expected to gain freedom.

American slaves began to believe that King George III was for them and against their masters as tensions increased before the American Revolution. Colonial slaveholders feared a British-inspired slave rebellion, and Lord Dunmore wrote to Lord Dartmouth in early 1775 of his intention to take advantage of the situation.[5]

Proclamations[edit]

Dunmore's Proclamation[edit]

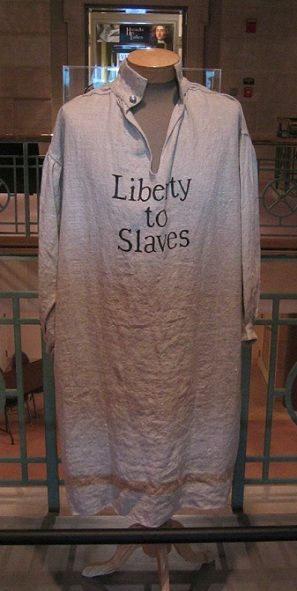

In November 1775, Lord Dunmore issued a controversial proclamation. As Virginia's royal governor, he called on all able-bodied men to assist him in the defence of the colony, including slaves belonging to the Patriots. He promised such slave recruits freedom in exchange for service in the British Army:

Evacuation and resettlement[edit]

When the British evacuated their troops from Charleston and New York after the war, they made good on their promises and took thousands of freed slaves with them. They resettled the freedmen in colonies in the Caribbean, such as Jamaica, and in Nova Scotia and Upper Canada, as well as transporting some to London. The Canadian climate and other factors made Nova Scotia difficult. In addition, the Poor Blacks of London, many former slaves, had trouble getting work. British abolitionists ultimately founded Freetown in what became Sierra Leone on the coast of West Africa, as a place to resettle Black Loyalists from London and Canada, and Jamaican Maroons. Nearly 2,000 Black Loyalists left Nova Scotia to help found the new colony in Africa. Their descendants are the Sierra Leone Creole people.[14][15][16][17]

Postwar treatment[edit]

When peace negotiations began after the siege of Yorktown, a primary issue of debate was the fate of Black British soldiers. Loyalists who remained in the United States wanted Black soldiers returned so their chances of receiving reparations for damaged property would be increased, but British military leaders fully intended to keep the promise of freedom made to Black soldiers despite the anger of the Americans.[22]

In the chaos as the British evacuated Loyalist refugees, particularly from New York and Charleston, many American slave owners attempted to recapture their former slaves. Some would capture any Black, including those born free before the war, and sell them into slavery.[23] The U.S. Congress ordered George Washington to retrieve any American property, including slaves, from the British, as stipulated by the Treaty of Paris of 1783.

Since Lieutenant General Guy Carleton intended to honor the promise of freedom, the British proposed a compromise that would compensate slave owners and provide certificates of freedom and the right to be evacuated to one of the British colonies to any Black person who could prove his service or status. The British transported more than 3,000 Black Loyalists to Nova Scotia, the greatest number of people of African descent to arrive there at any one time. One of their settlements, Birchtown, Nova Scotia was the largest free African community in North America for the first few years of its existence.[24]

Black Loyalists found the northern climate and frontier conditions in Nova Scotia difficult and were subject to discrimination by other Loyalist settlers, many of them slaveholders. In July 1784, Black Loyalists in Shelburne were targeted in the Shelburne Riots, the first recorded race riots in Canadian history. Crown officials granted land to the Black Loyalists of lesser quality and that were more rocky and less fertile than that given to White Loyalists. In 1792, the British government offered Black Loyalists the chance to resettle in a new colony in Sierra Leone. The Sierra Leone Company was established to manage its development. Half of the Black Loyalists in Nova Scotia, nearly 1200, departed the country and moved permanently to Sierra Leone. They set up the community of "Freetown".[25]

In 1793, the British transported another 3,000 Blacks to Florida, Nova Scotia and England as free men and women.[26] Their names were recorded in the Book of Negroes by Sir Carleton.[27][28]

Approximately 300 free Black people in Savannah refused to evacuate at the end of the war, fearing they would be re-enslaved once they arrived in the West Indies. They established an independent colony in swamps near Savannah River, though by 1786 most of them were discovered and returned to slavery, as Southern planters ignored the fact that they had been freed by the British during the war. When the British ceded the colonies of East Florida and West Florida back to Spain per the terms of the Treaty of Paris, hundreds of free Black people which had been transported there from the South were left behind as British forces pulled out of the region.[29]