Prominent Loyalists repeatedly assured the British government that many thousands of them would spring to arms and fight for the Crown. The British government acted in expectation of that, especially during the Southern campaigns of 1780 and 1781. Britain was able to effectively protect the people only in areas where they had military control, and in return, the number of military Loyalists was significantly lower than what had been expected. Due to conflicting political views, loyalists were often under suspicion of those in the British military, who did not know whom they could fully trust in such a conflicted situation; they were often looked down upon.[4]

Patriots watched suspected Loyalists very closely and would not tolerate any organized Loyalist opposition. Many outspoken or militarily active Loyalists were forced to flee, especially to their stronghold of New York City. William Franklin, the royal governor of New Jersey and son of Patriot leader Benjamin Franklin, became the leader of the Loyalists after his release from a Patriot prison in 1778. He worked to build Loyalist military units to fight in the war. Woodrow Wilson wrote that

When their cause was defeated, about 15 percent of the Loyalists (65,000–70,000 people) fled to other parts of the British Empire; especially to Britain itself, or to British North America (now Canada).[6] The southern Loyalists moved mostly to Florida, which had remained loyal to the Crown, and to British Caribbean possessions. Northern Loyalists largely migrated to Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. They called themselves United Empire Loyalists. Most were compensated with Canadian land or British cash distributed through formal claims procedures. Loyalists who left the US received over £3 million or about 37% of their losses from the British government. Loyalists who stayed in the US were generally able to retain their property and become American citizens.[7] Many Loyalists eventually returned to the US after the war and discriminatory laws had been repealed.[8] Historians have estimated that between 15% and 20% (300,000 to 400,000) of the 2,000,000 whites in the colonies in 1775 were Loyalists.[9]

Loyalist (American Revolution)

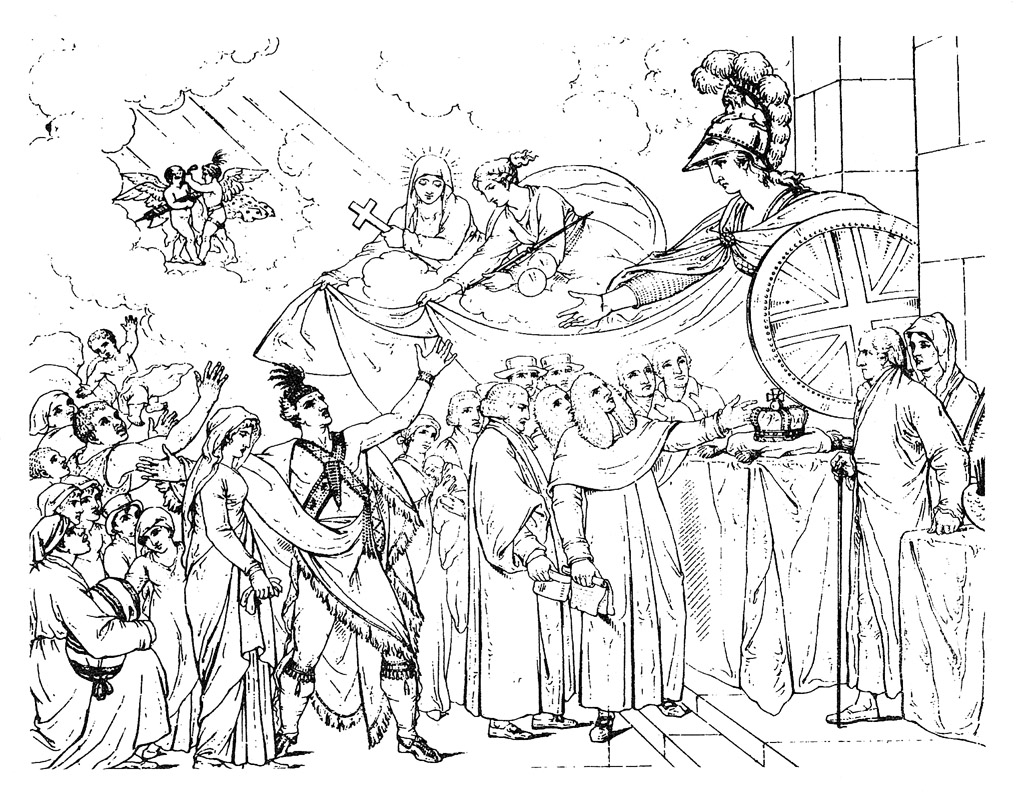

Loyalists were colonists in the Thirteen Colonies who remained loyal to the British Crown during the American Revolutionary War, often referred to as Tories,[1][2] Royalists or King's Men at the time. They were opposed by the Patriots, who supported the revolution, and called them "persons inimical to the liberties of America."[3]

For other uses, see Loyalism and Loyalist (disambiguation).$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#0__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#0__subtitleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#0__call_to_action.textDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#9__descriptionDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

Return of some expatriates[edit]

The great majority of Loyalists never left the United States; they stayed on and were allowed to be citizens of the new country. Some became nationally prominent leaders, including Samuel Seabury, who was the first Bishop of the Episcopal Church, and Tench Coxe. There was a small, but significant trickle of returnees who found life in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick too difficult. Perhaps 10% of the refugees to New Brunswick returned to the States as did an unknown number from Nova Scotia.[69] Some Massachusetts Tories settled in the Maine District. Nevertheless, the vast majority never returned. Captain Benjamin Hallowell, who as Mandamus Councilor in Massachusetts served as the direct representative of the Crown, was considered by the insurgents as one of the most hated men in the Colony, but as a token of compensation when he returned from England in 1796, his son was allowed to regain the family house.[70]

Alexander Hamilton enlisted the help of the Tories (ex-Loyalists) in New York in 1782–85 to forge an alliance with moderate Whigs to wrest the State from the power of the Clinton faction. Moderate Whigs in other States who had not been in favor of separation from Britain but preferred a negotiated settlement which would have maintained ties to the Mother Country mobilized to block radicals. Most States had rescinded anti-Tory laws by 1787, although the accusation of being a Tory was heard for another generation. Several hundred who had left for Florida returned to Georgia in 1783–84. South Carolina which had seen a bitter bloody internal civil war in 1780–82 adopted a policy of reconciliation that proved more moderate than any other state. About 4500 white Loyalists left when the war ended, but the majority remained behind. The state government successfully and quickly reincorporated the vast majority. During the war, pardons were offered to Loyalists who switched sides and joined the Patriot forces. Others were required to pay a 10% fine of the value of the property. The legislature named 232 Loyalists liable for the confiscation of their property, but most appealed and were forgiven.[71] In Connecticut much to the disgust of the Radical Whigs the moderate Whigs were advertising in New York newspapers in 1782–83 that Tories who would make no trouble would be welcome on the grounds that their skills and money would help the State's economy. The Moderates prevailed. All anti-Tory laws were repealed in early 1783 except for the law relating to confiscated Tory estates: "... the problem of the loyalists after 1783 was resolved in their favor after the War of Independence ended." In 1787 the last of any discriminatory laws were rescinded.[72]

Videos

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#7__descriptionDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#3__descriptionDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#2__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

Families were often divided during the American Revolution, and many felt themselves to be both American and British, still owing loyalty to the mother country. Maryland lawyer Daniel Dulaney the Younger opposed taxation without representation but would not break his oath to the King or take up arms against him. He wrote: "There may be a time when redress may not be obtained. Till then, I shall recommend a legal, orderly, and prudent resentment".[10] Most Americans hoped for a peaceful reconciliation but were forced to choose sides by the Patriots who took control nearly everywhere in the Thirteen Colonies in 1775–76.[11]

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#1__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#1__descriptionDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

Yale historian Leonard Woods Larabee has identified eight characteristics of the Loyalists that made them essentially conservative and loyal to the King and to Britain:[12]

Other motives of the Loyalists included:

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#5__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#5__descriptionDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#4__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#4__subtextDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#4__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#4__subtextDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#6__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#6__subtextDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#6__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#6__subtextDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#3__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#2__titleDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$

$_$_$DEEZ_NUTS#2__subtextDEEZ_NUTS$_$_$