British expedition to Tibet

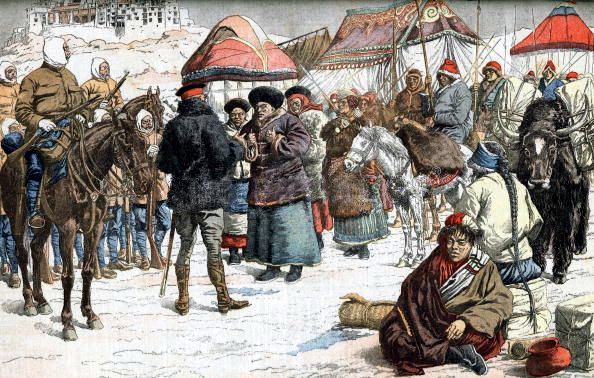

The British expedition to Tibet, also known as the Younghusband expedition,[2] began in December 1903 and lasted until September 1904. The expedition was effectively a temporary invasion by British Indian Armed Forces under the auspices of the Tibet Frontier Commission, whose purported mission was to establish diplomatic relations and resolve the dispute over the border between Tibet and Sikkim.[3] In the nineteenth century, the British had conquered Burma and Sikkim, with the whole southern flank of Tibet coming under the control of the British Indian Empire. Tibet ruled by the Dalai Lama under the Ganden Phodrang government was a Himalayan state under the protectorate (or suzerainty) of the Chinese Qing dynasty until the 1911 Revolution, after which a period of de facto Tibetan independence (1912–1951) followed.

The invasion was intended to counter the Russian Empire's perceived ambitions in the East and was initiated largely by Lord Curzon, the head of the British Indian government. Curzon had long held deep concerns over Russia's advances in central Asia and now feared a Russian invasion of British India.[4] In April 1903, the British government received clear assurances from Russia that it had no interest in Tibet. "In spite, however, of the Russian assurances, Lord Curzon continued to press for the dispatch of a mission to Tibet", a high level British political officer noted.[5]

The expeditionary force fought its way to Gyantse and eventually reached Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, in August 1904. The Dalai Lama had fled to safety, first to Mongolia and then to China proper. The poorly-trained and equipped Tibetans proved no match for the modern equipment and training of the British Indian forces. At Lhasa, the Commission forced remaining Tibetan officials to sign the Convention of Lhasa, before withdrawing to Sikkim in September, with the understanding the Chinese government would not permit any other country to interfere with the administration of Tibet.[6]

The mission was recognized as a military expedition by the British Indian government, which issued a campaign medal, the Tibet Medal, to all those who took part.[7][8]

Subsequent interpretations[edit]

Many Chinese historians have written concerning the expedition an image of Tibetans heroically opposing the expeditionary force out of loyalty not to Tibet, but to China. This particular school of Chinese historiography asserts that the British interest in trade and resolving the Tibet-Sikkim border disputes was a pretext for annexing the whole Tibet region into British India, which was a step towards the ultimate goal of annexing all of China. They also assert that the Tibetans annihilated the British forces, and that Younghusband escaped only with a small retinue.[59] The Chinese government has turned Gyantze Dzong into a "Resistance Against the British Museum", promoting these views, as well as other themes such as the brutal living conditions endured by Tibetan serfs who supposedly loved their motherland (China).[60]

Meanwhile, many Tibetans look back to it as an exercise of Tibetan self-defence and an act of independence from the Qing dynasty as the dynasty was falling apart, and its growing disdain for China in the aftermath due to ruthless repression of Tibetans at 1905.[61]

The British writer and popular historian Charles Allen has remarked that, although the Younghusband Mission did inflict "considerable material damage on Tibet and its people", it was damage that paled into insignificance when compared "to the invasion of Tibet by the Chinese People's Liberation Army in 1951 and the Cultural Revolution of 1966–1967".[62]