British Raj

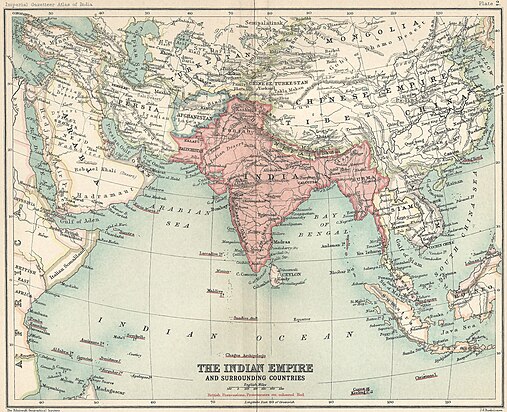

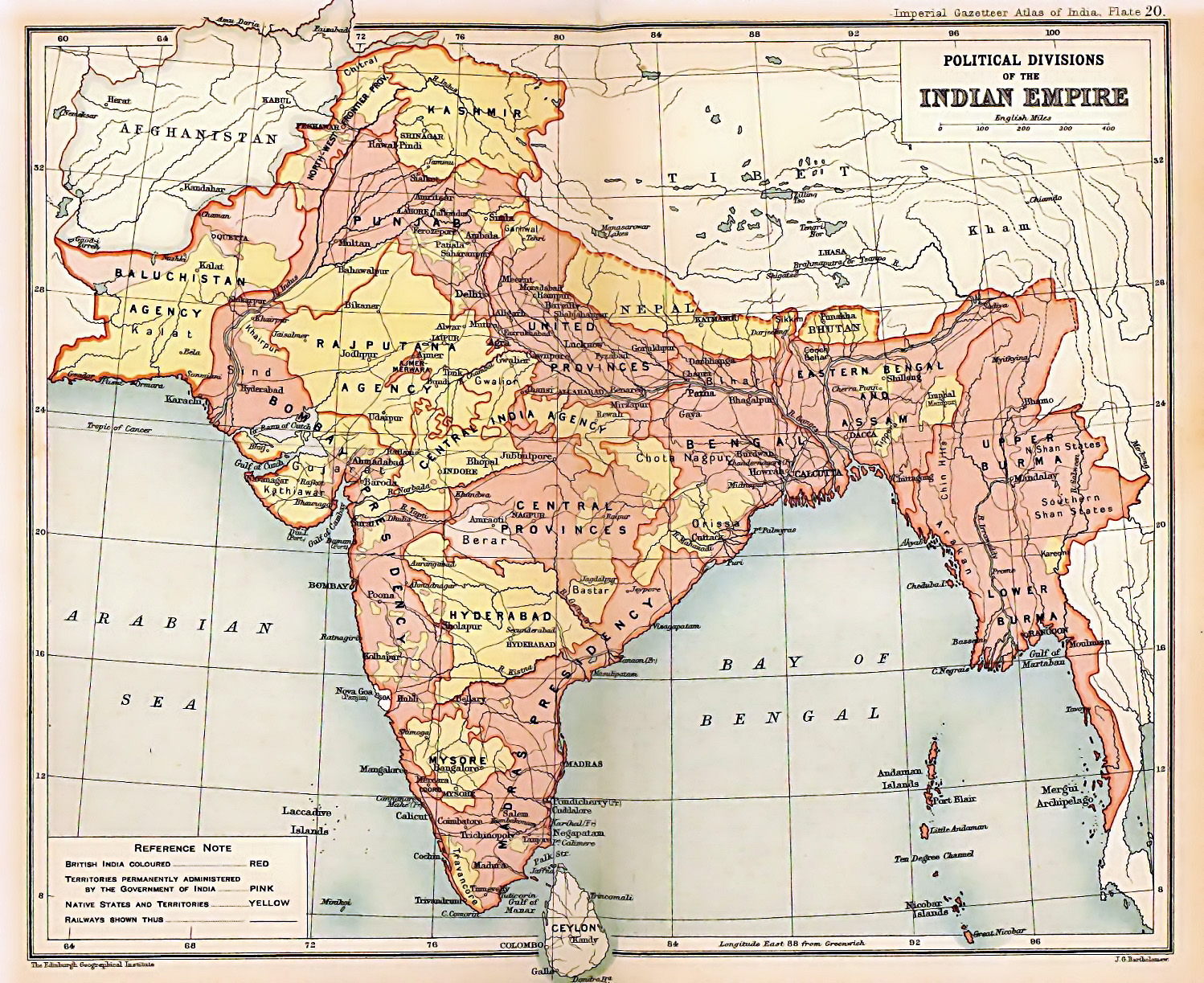

The British Raj (/rɑːdʒ/ RAHJ; from Hindi rāj, 'kingdom', 'realm', 'state', or 'empire')[11][a] was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;[13] it is also called Crown rule in India,[14] or Direct rule in India,[15] and lasted from 1858 to 1947.[16] The region under British control was commonly called India in contemporaneous usage and included areas directly administered by the United Kingdom, which were collectively called British India, and areas ruled by indigenous rulers, but under British paramountcy, called the princely states. The region was sometimes called the Indian Empire, though not officially.[17]

This article is about the rule of India by the British Crown from 1858 to 1947. For the rule of the East India Company from 1757 to 1858, see Company rule in India. For British directly-ruled administrative divisions in India, see Presidencies and provinces of British India.

India

Imperial political structure (comprising British India[a] and the Princely States[b][1]

Indians, British Indians

10 May 1857

2 August 1858

18 July 1947

took effect Midnight, 14–15 August 1947

As India, it was a founding member of the League of Nations, a participating state in the Summer Olympics in 1900, 1920, 1928, 1932, and 1936, and a founding member of the United Nations in San Francisco in 1945.[18]

This system of governance was instituted on 28 June 1858, when, after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the rule of the East India Company was transferred to the Crown in the person of Queen Victoria[19] (who, in 1876, was proclaimed Empress of India). It lasted until 1947, when the British Raj was partitioned into two sovereign dominion states: the Union of India (later the Republic of India) and Pakistan (later the Islamic Republic of Pakistan). Later, the People's Republic of Bangladesh gained independence from Pakistan. At the inception of the Raj in 1858, Lower Burma was already a part of British India; Upper Burma was added in 1886, and the resulting union, Burma, was administered as an autonomous province until 1937, when it became a separate British colony, gaining its own independence in 1948. It was renamed Myanmar in 1989. The Chief Commissioner's Province of Aden was also part of British India at the inception of the British Raj, and became a separate colony known as Aden Colony in 1937 as well.

The British Raj extended over almost all present-day India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, except for small holdings by other European nations such as Goa and Pondicherry.[20] This area is very diverse, containing the Himalayan mountains, fertile floodplains, the Indo-Gangetic Plain, a long coastline, tropical dry forests, arid uplands, and the Thar Desert.[21] In addition, at various times, it included Aden (from 1858 to 1937),[22] Lower Burma (from 1858 to 1937), Upper Burma (from 1886 to 1937), British Somaliland (briefly from 1884 to 1898), and the Straits Settlements (briefly from 1858 to 1867). Burma was separated from India and directly administered by the British Crown from 1937 until its independence in 1948. The Trucial States of the Persian Gulf and the other states under the Persian Gulf Residency were theoretically princely states as well as presidencies and provinces of British India until 1947 and used the rupee as their unit of currency.[23]

Among other countries in the region, Ceylon, which was referred to coastal regions and northern part of the island at that time (now Sri Lanka) was ceded to Britain in 1802 under the Treaty of Amiens. These coastal regions were temporarily administered under Madras Presidency between 1793 and 1798,[24] but for later periods the British governors reported to London, and it was not part of the Raj. The kingdoms of Nepal and Bhutan, having fought wars with the British, subsequently signed treaties with them and were recognised by the British as independent states.[25][26] The Kingdom of Sikkim was established as a princely state after the Anglo-Sikkimese Treaty of 1861; however, the issue of sovereignty was left undefined.[27] The Maldive Islands were a British protectorate from 1887 to 1965, but not part of British India.[28]

This is the list of civilian massacre of Indians, in most cases unarmed peaceful crowds, by the British colonial troops.