Notre-Dame de Paris

Notre-Dame de Paris (French: [nɔtʁ(ə) dam də paʁi] ; meaning "Our Lady of Paris"), referred to simply as Notre-Dame,[a] is a medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the Seine River), in the 4th arrondissement of Paris, France. The cathedral, dedicated to the Virgin Mary, is considered one of the finest examples of French Gothic architecture. Several attributes set it apart from the earlier Romanesque style, particularly its pioneering use of the rib vault and flying buttress, its enormous and colourful rose windows, and the naturalism and abundance of its sculptural decoration.[6] Notre-Dame also stands out for its three pipe organs (one historic) and its immense church bells.[7]

This article is about the French cathedral. For other uses, see Notre-Dame de Paris (disambiguation).Notre-Dame de Paris

France

Replaced the Cathedral of Etienne

24 March 1163 to 25 April 1163 (laying of the cornerstone)

19 May 1182 (high altar)

Crown of Thorns, a nail from the Cross, and a sliver of the Cross

Closed/Under renovation after the 2019 fire

1163–1345

1163

1345

128 m (420 ft)

48 m (157 ft)

35 metres (115 ft)[1]

2

69 m (226 ft)

1 (the third, completed 16 December 2023)[2]

96 m (315 ft)

Limestone

10 (bronze)

Olivier Ribadeau Dumas

Sylvain Dieudonné[3]

Philippe Lefebvre (since 1985); Olivier Latry (since 1985); and Vincent Dubois (since 2016)

I, II, IV[4]

1991

Paris, Banks of the Seine

600

Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris

Cathédrale

1862[5]

PA00086250

Built during the medieval era, construction of the cathedral began in 1163 under Bishop Maurice de Sully and was largely completed by 1260, though it was modified in succeeding centuries. In the 1790s, during the French Revolution, Notre-Dame suffered extensive desecration; much of its religious imagery was damaged or destroyed. In the 19th century, the coronation of Napoleon and the funerals of many of the French Republic's presidents took place at the cathedral. The 1831 publication of Victor Hugo's novel Notre-Dame de Paris (in English: The Hunchback of Notre-Dame) inspired interest which led to restoration between 1844 and 1864, supervised by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. On 26 August 1944, the Liberation of Paris from German occupation was celebrated in Notre-Dame with the singing of the Magnificat. Beginning in 1963, the cathedral's façade was cleaned of soot and grime. Another cleaning and restoration project was carried out between 1991 and 2000.[8] A fire in April 2019 caused serious damage and forced the cathedral to close for five years; it is planned to reopen on 8 December 2024.

The cathedral is a widely recognized symbol of the city of Paris and the French nation. In 1805, it was awarded honorary status as a minor basilica. As the cathedral of the archdiocese of Paris, Notre-Dame contains the cathedra of the archbishop of Paris (currently Laurent Ulrich). In the early 21st century, approximately 12 million people visited Notre-Dame annually, making it the most visited monument in Paris.[9] The cathedral is renowned for its Lent sermons, a tradition founded in the 1830s by the Dominican Jean-Baptiste Henri Lacordaire. These sermons have increasingly been given by leading public figures or government-employed academics.

Over time, the cathedral has gradually been stripped of many decorations and artworks. However, the cathedral still contains Gothic, Baroque, and 19th-century sculptures, 17th- and early 18th-century altarpieces, and some of the most important relics in Christendom – including the Crown of Thorns, and a sliver and nail from the True Cross.

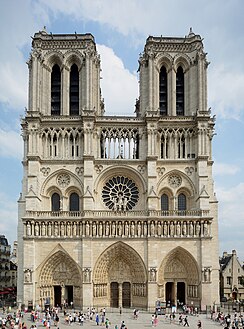

The two towers are 69 metres (226 ft) high. The towers were the last major element of the cathedral to be constructed. The south tower was built first, between 1220 and 1240, and the north tower between 1235 and 1250. The newer north tower is slightly larger, as can be seen when they are viewed from directly in front of the church. The contrefort or buttress of the north tower is also larger.[122] The cathedral's main peal of bells is within these towers.

The south tower was accessible to visitors by a stairway, whose entrance was on the south side of the tower. The stairway has 387 steps, and has a stop at the Gothic hall at the level of the rose window, where visitors could look over the parvis and see a collection of paintings and sculpture from earlier periods of the cathedral's history.

The cathedral's flèche (or spirelet) was located over the transept. The original flèche was constructed in the 13th century, probably between 1220 and 1230. It was battered, weakened and bent by the wind over five centuries, and finally was removed in 1786. During the 19th-century restoration, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc recreated it, making a new version of oak covered with lead. The entire flèche weighed 750 tonnes.

Following Viollet-le-Duc's plans, the flèche was surrounded by copper statues of the twelve Apostles—a group of three at each point of the compass. In front of each group is a symbol representing one of the four evangelists: a winged ox for Saint Luke,[123] a lion for Saint Mark, an eagle for Saint John and an angel for Saint Matthew. Just days prior to the fire, the statues were removed for restoration.[124] While in place, they had faced outwards towards Paris, except one: the statue of Saint Thomas, the patron saint of architects, faced the flèche, and had the features of Viollet-le-Duc.

The rooster weathervane at the top of the flèche contained three relics: a tiny piece from the Crown of Thorns in the cathedral treasury, and relics of Saint Denis and Saint Genevieve, patron saints of Paris. They were placed there in 1935 by Archbishop Jean Verdier, to protect the congregation from lightning or other harm. The rooster with relics intact was recovered in the rubble shortly after the fire.[125]

The Gothic cathedral was a liber pauperum, a "poor people's book", covered with sculptures vividly illustrating biblical stories, for the vast majority of parishioners who were, at the time, illiterate. To add to the effect, all of the sculpture on the façades was originally painted and gilded.[126]

The tympanum over the central portal on the west façade, facing the square, vividly illustrates the Last Judgment, with figures of sinners being led off to hell, and good Christians taken to heaven. The sculpture of the right portal shows the coronation of the Virgin Mary, and the left portal shows the lives of saints who were important to Parisians, particularly Saint Anne, the mother of the Virgin Mary.[127]

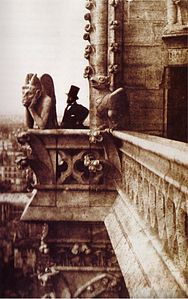

The exteriors of cathedrals and other Gothic churches were also decorated with sculptures of grotesques or monsters. These included the gargoyle, the chimera, a mythical hybrid creature which usually had the body of a lion and the head of a goat, and the Strix or stryge, a creature resembling an owl or bat, which was said to eat human flesh. The strix appeared in classical Roman literature; it was described by the Roman poet Ovid, who was widely read in the Middle Ages, as a large-headed bird with transfixed eyes, rapacious beak, and greyish white wings.[128] They were part of the visual message for the illiterate worshipers, symbols of the evil and danger that threatened those who did not follow the teachings of the church.[129]

The gargoyles, which were added in about 1240, had a more practical purpose. They were the rain spouts of the cathedral, designed to divide the torrent of water which poured from the roof after rain, and to project it outwards as far as possible from the buttresses and the walls and windows where it might erode the mortar binding the stone. To produce many thin streams rather than a torrent of water, a large number of gargoyles were used, so they were also designed to be a decorative element of the architecture. The rainwater ran from the roof into lead gutters, then down channels on the flying buttresses, then along a channel cut in the back of the gargoyle and out of the mouth away from the cathedral.[126]

Amid all the religious figures, some of the sculptural decoration was devoted to illustrating medieval science and philosophy. The central portal of the west façade is decorated with carved figures holding circular plaques with symbols of transformation taken from alchemy. The central pillar of the central door of Notre-Dame features a statue of a woman on a throne holding a sceptre in her left hand, and in her right hand, two books, one open (symbol of public knowledge), and the other closed (esoteric knowledge), along with a ladder with seven steps, symbolizing the seven steps alchemists followed in their scientific quest of trying to transform ordinary metals into gold.[129] On each side of the west façade, there are statues of Ecclesia and Synagoga. The statues represent supersessionism, the Christian belief that Christianity has replaced Judaism.[130]

Many of the statues, particularly the grotesques, were removed from the façade in the 17th and 18th centuries, or were destroyed during the French Revolution. They were replaced with figures in the Gothic style, designed by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, during the 19th-century restoration.

The stained glass windows of Notre-Dame, particularly the three rose windows, are among the most famous features of the cathedral. The west rose window, over the portals, was the first and smallest of the roses in Notre-Dame. It is 9.6 metres (31 ft) in diameter, and was made in about 1225, with the pieces of glass set in a thick circular stone frame. None of the original glass remains in this window; it was recreated in the 19th century.[131]

The two transept windows are larger and contain a greater proportion of glass than the rose on the west façade, because the new system of buttresses made the nave walls thinner and stronger. The north rose was created in about 1250, and the south rose in about 1260. The south rose in the transept is particularly notable for its size and artistry. It is 12.9 metres (42 ft) in diameter; with the claire-voie surrounding it, a total of 19 metres (62 ft). It was given to the cathedral by King Louis IX of France, known as Saint Louis.[132]

The south rose has 94 medallions, arranged in four circles, depicting scenes from the life of Christ and those who witnessed his time on earth. The inner circle has twelve medallions showing the twelve apostles. (During later restorations, some of these original medallions were moved to circles farther out). The next two circles depict celebrated martyrs and virgins. The fourth circle shows twenty angels, as well as saints important to Paris, notably Saint Denis, Margaret the Virgin with a dragon, and Saint Eustace. The third and fourth circles also have some depictions of Old Testament subjects. The third circle has some medallions with scenes from the New Testament Gospel of Matthew which date from the last quarter of the 12th century. These are the oldest glass in the window.[132]

Additional scenes in the corners around the rose window include Jesus' Descent into Hell, Adam and Eve, the Resurrection of Christ. Saint Peter and Saint Paul are at the bottom of the window, and Mary Magdalene and John the Apostle at the top.

Above the rose was a window depicting Christ triumphant seated in the sky, surrounded by his Apostles. Below are sixteen windows with painted images of Prophets. These were not part of the original window; they were painted during the restoration in the 19th century by Alfred Gérenthe, under the direction of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, based upon a similar window at Chartres Cathedral.[132]

The south rose had a difficult history. In 1543 it was damaged by the settling of the masonry walls, and not restored until 1725–1727. It was seriously damaged in the French Revolution of 1830. Rioters burned the residence of the archbishop, next to the cathedral, and many of the panes were destroyed. The window was entirely rebuilt by Viollet-le-Duc in 1861. He rotated the window by fifteen degrees to give it a clear vertical and horizontal axis, and replaced the destroyed pieces of glass with new glass in the same style. The window today contains both medieval and 19th-century glass.[132]

In the 1960s, after three decades of debate, it was decided to replace many of the 19th-century grisaille windows in the nave designed by Viollet-le-Duc with new windows. The new windows, made by Jacques Le Chevallier, are without human figures and use abstract grisaille designs and colour to try to recreate the luminosity of the cathedral's interior in the 13th century.

The massive fire left the three great medieval rose windows essentially intact, but with some damage.[133] The rector of the Cathedral noted that one rose window would have to be dismantled, as it was unstable and at risk.[134] Most of the other damaged windows were of much less historical value.[134]

Unlike some other French cathedrals, Notre-Dame was originally constructed without a crypt. In the medieval period, burials were made directly into the floor of the church, or in above-ground sarcophagi, some with tomb effigies (French: gisant). High-ranking clergy and some royals were buried in the choir and apse, while many others, including lower-ranking clergy and lay people, were buried in the nave or chapels. There is no surviving complete record of all of the burials.

In 1699, many of the choir tombs were disturbed or covered over during a major renovation project. Remains which were exhumed were reburied in a common tomb beside the high altar. In 1711, a small crypt measuring about six by six metres (20 by 20 ft) was dug out in the middle of the choir which was used as a burial vault for the archbishops, if they had not requested to be buried elsewhere. It was during this excavation that the 1st-century Pillar of the Boatmen was discovered.[135] In 1758, three more crypts were dug in the Chapel of Saint-Georges to be used for burials of canons of Notre-Dame. In 1765, a larger crypt was built under the nave to be used for burials of canons, beneficiaries, chaplains, cantors, and choirboys. Between 1771 and 1773, the cathedral floor was repaved with black and white marble tiles, which covered over most of the remaining tombs. This prevented many of these tombs from being disturbed during the French Revolution.

In 1858, the choir crypt was expanded to stretch most of the length of the choir. During this project, many medieval tombs were rediscovered. Likewise the nave crypt was also rediscovered in 1863 when a larger vault was dug out to install a vault heater. Many other tombs are also located in the chapels.[136][137]

Notre-Dame currently has ten bells. The two largest bells, Emmanuel and Marie, are mounted in the south tower. The eight others; Gabriel, Anne Geneviève, Denis, Marcel, Étienne, Benoît-Joseph, Maurice, and Jean-Marie; are mounted in the north tower. In addition to accompanying regular activities at the cathedral, the bells have also rung to commemorate events of national and international significance, such as the armistice of 11 November 1918, the liberation of Paris, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the September 11 attacks.

The bells are made with bronze for its resonance and resistance to corrosion. During the medieval period, they were often founded on the grounds of the cathedral so they would not need to be transported long distances.[138] According to tradition, the bishop of Paris held a ceremony in which he blessed and baptized the bells, and a godparent formally bestowed a name on the bell. Most of the cathedral's early bells were named after the person who donated them, but they were also named after biblical figures, saints, bishops, and others.

After the baptism, the bells were hoisted into the towers through circular openings in the vaulted ceilings and mounted to headstocks to allow the bells to swing. Notre-Dame's bells swing on a straight swinging axis, meaning the axis of rotation is just above the crown of the bell. This style of ringing produces a clearer tone, as the clapper strikes the bell on the upswing, called a flying clapper. However, it also causes great horizontal forces, which can be up to one and a half times the weight of the bell.[139] For this reason the bells are mounted within wooden belfries which are recessed from the towers' stone walls. These absorb the horizontal forces and prevent the bells from damaging the relatively brittle stonework.[140] The current belfries date to the 19th-century restoration.

Before the French Revolution, it was common for the bells to break, and they were often removed for repairs or to be entirely recast, and sometimes renamed. The bell Guillaume, for example, was renamed three times and recast no less than five times between 1230 and 1770.

The practice of bell-ringing at Notre-Dame is recorded as early as 1198.[140] By the end of the 14th century the bells were marking the civil hours, and in 1472 they began to call to prayer for the Angelus three times a day, both practices which continue today. During the French Revolution, most of the cathedral's bells were removed and melted down. While many of them bore the names of the medieval bells, most were relatively recent recastings made from most of the same metal. During the 19th-century restoration, four new bells were made for the north tower. These were replaced in 2012 with nine as part of the cathedral's 850th anniversary celebration.

In addition to the main bells, the cathedral has also had smaller secondary bells. These included a carillon in the medieval flèche, three clock bells on the north transept in the 18th century, and six bells added in the 19th century – three in the reconstructed flèche and three within the roof to be heard in the sanctuary.[141] These were destroyed during the 2019 fire.

Ownership[edit]

Until the French Revolution, Notre-Dame was the property of the archbishop of Paris and therefore the Roman Catholic Church. It was nationalized on 2 November 1789 and since then has been the property of the French state.[149] Under the Concordat of 1801, use of the cathedral was returned to the Church, but not ownership. Legislation from 1833 and 1838 clarified that cathedrals were maintained at the expense of the French government. This was reaffirmed in the 1905 law on the separation of Church and State, designating the Catholic Church as having the exclusive right to use it for religious purposes in perpetuity. Notre-Dame is one of seventy historic churches in France with this status. The archdiocese is responsible for paying the employees, for security, heating and cleaning, and for ensuring that the cathedral is open free of charge to visitors. The archdiocese does not receive subsidies from the French state.[150][151]

![Circular utility door (right of center) in the ceiling below the north tower made for raising and lowering bells[140]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6c/Notre-dame-de-paris-vue-interieure-salle-nord.jpg/495px-Notre-dame-de-paris-vue-interieure-salle-nord.jpg)

![The bourdon Emmanuel, Notre-Dame's largest and oldest bell, cast in 1686[142]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/46/Bourdon_Emmanuel_in_2016_%2836378821523%29.jpg/247px-Bourdon_Emmanuel_in_2016_%2836378821523%29.jpg)

![1767 illustration of a bell headstock and mounting components (left) and Notre-Dame's original south belfry (right)[143][c]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fd/Encyclopedie_volume_4-176pl7_%282%29.jpg/228px-Encyclopedie_volume_4-176pl7_%282%29.jpg)

![1854 illustration by Pégard showing the 1850 belfry which is present today[144]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/85/Coupe.beffroi.cathedrale.Paris.2.png/162px-Coupe.beffroi.cathedrale.Paris.2.png)