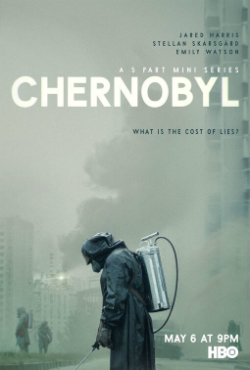

Chernobyl (miniseries)

Chernobyl is a 2019 historical drama television miniseries that revolves around the Chernobyl disaster of 1986 and the cleanup efforts that followed. The series was created and written by Craig Mazin and directed by Johan Renck. It features an ensemble cast led by Jared Harris, Stellan Skarsgård, Emily Watson, and Paul Ritter. The series was produced by HBO in the United States and Sky UK in the United Kingdom.

Chernobyl

Craig Mazin

- United States

- United Kingdom

English

5

- Craig Mazin

- Carolyn Strauss

- Jane Featherstone

- Lithuania

- Ukraine

Jakob Ihre

- Jinx Godfrey

- Simon Smith

65–78 minutes

- HBO (US)

- Sky Atlantic (UK)

May 6 –

June 3, 2019

The five-part series premiered simultaneously[a] in the United States on May 6, 2019, and in the United Kingdom on May 7. It received widespread critical acclaim for its cinematography, historical accuracy, performances, atmosphere, tone, screenplay, and musical score. At the 71st Primetime Emmy Awards, it received nineteen nominations and won for Outstanding Limited Series, Outstanding Directing, and Outstanding Writing, while Harris, Skarsgård, and Watson received acting nominations. At the 77th Golden Globe Awards, the series won for Best Miniseries or Television Film and Skarsgård won for Best Supporting Actor in a Series, Miniseries or Television Film.[2][3]

The release of each episode was accompanied by a podcast in which Mazin and NPR host Peter Sagal discuss instances of artistic license and the reasoning behind them.[4] While critics, experts and witnesses have noted historical and factual discrepancies in the series, the creators' attention to detail has been widely praised.[5][6]

Premise[edit]

Chernobyl dramatizes the story of the April 1986 nuclear plant disaster which occurred in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Soviet Union, telling the stories of the people who were involved in the disaster and those who responded to it.[7] The series depicts some of the lesser-known stories of the disaster, including the efforts of the firefighters who were the first responders on the scene, volunteers, and teams of miners who dug a critical tunnel under Reactor 4.

The miniseries is based in large part on the recollections of Pripyat locals, as told by Belarusian Nobel laureate Svetlana Alexievich in her book Voices from Chernobyl.[8] Researchers have documented Alexievich's insertion of her own words into the testimonies of her interview subjects in this and others of her books, as well as her extensive revision—even from one edition to the next—of her interviews, which suggests that her works should not be taken as straightforward history.[9][10]

Historical accuracy[edit]

The series was praised in the media for being exhaustively researched,[45] but some commentators noted inaccuracies or liberties were taken for dramatic purposes, such as Legasov being present at the trial.[46][47] The first episode depicts Legasov timing his suicide down to the second (1:23:45) to coincide with the second anniversary of the Chernobyl explosion. Legasov actually committed suicide a day later. The epilogue acknowledges that the character of Ulana Khomyuk is fictional, a composite of Soviet scientists. Journalist Adam Higginbotham, who spent a decade researching the disaster and authored the non-fiction account Midnight in Chernobyl, points out in an interview that there was no need for scientists to "uncover the truth" because "many nuclear scientists knew all along that there were problems with this reactor—the problems that led ultimately to an explosion and disaster".[48] Artistic license was also used in the depiction of the "Bridge of Death", from which spectators in Pripyat watched the aftermath of the explosion; the miniseries asserts that the spectators subsequently died, a claim which is now generally held to be an urban legend.[49][50][51]

The series also discusses a potential third steam explosion, due to the risk of corium melting through to the water reservoirs below the reactor building, as being in the range of 2 to 4 megatons. This would have been physically impossible under the circumstances, as exploding reactors do not function as thermonuclear bombs.[52][53] According to series author Craig Mazin, the claim was based on one made by Belarusian nuclear physicist Vassili Nesterenko about a potential 3–5 Mt third explosion, even though physicists hired for the show were unable to confirm its plausibility.[54]

The series' production design, such as the choice of sets, props, and costumes, has received high praise for its accuracy. Several sources have commended the attention to even minor setting details, such as the use of actual Kyiv-region license plate numbers, and a New Yorker review states that "the material culture of the Soviet Union is reproduced with an accuracy that has never before been seen" from either Western or Russian filmmakers.[55][48][5][56] Oleksiy Breus, a Chernobyl engineer, commends the portrayal of the symptoms of radiation poisoning;[57] Robert Gale, a doctor who treated Chernobyl victims, states that the miniseries overstated the symptoms by suggesting that the patients were radioactive.[58] In a more critical judgment, a review from the Moscow Times highlights some small design errors: for instance, Soviet soldiers are inaccurately shown as holding their weapons in Western style and Legasov's apartment was too "dingy" for a scientist of his status.[59]

In a 1996 interview, Lyudmilla Ignatenko said that her baby "took the whole radioactive shock [...] She was like a lightning rod for it".[60] This perception that her husband, Vasily, was radioactive and caused the death of her daughter soon after birth was recreated in the miniseries. However, Ukrainian medical responder Alla Shapiro, in a 2019 interview with Vanity Fair, said such beliefs were false, and that once Ignatenko was showered and out of his contaminated clothing, he would not have been dangerous to others, precluding this possibility.[61] During an interview to BBC News Russian in 2019, Lyudmilla Ignatenko described how she suffered harassment and criticism when the series was aired. She claimed reporters hounded her at home in Moscow and even jammed their foot in her door as they tried to interview her, and that she suffered criticism for exposing her unborn daughter to Vasily, despite the fact she hadn't known anything about radiation then and that risk to a fetus from such exposure is infinitesimally small.[58] She said she never gave HBO and Sky Atlantic permission to tell her story, saying there had been a single phone call offering money after filming had been completed. She thought the call was a hoax because it came from a Moscow number and hung up. HBO Sky rejects this, saying they had exchanges with Lyudmilla before, during and after filming with the opportunity to participate and provide feedback and at no time did she express a wish for her story to not be included.[62]

The portrayal of Soviet officials, including the plant management and central government figures, received some criticism. Breus, the Chernobyl engineer, argues that the characters of Viktor Bryukhanov, Nikolai Fomin and Anatoly Dyatlov were "distorted and misrepresented, as if they were villains".[57] Some reviews criticized the series for creating a stark moral dichotomy, in which the scientists are depicted as overly heroic while the government and plant officials are uniformly villainous.[55][63][64][65] The occasional threats of execution from government officials were also seen by some as anachronistic: Masha Gessen of the New Yorker argues that "summary executions, or even delayed executions on orders of a single apparatchik, were not a feature of Soviet life after the nineteen-thirties".[55][59] Higginbotham takes a more positive view of the portrayal of the authorities, arguing that the unconcerned attitude of the central government was accurately depicted.[48]

Reception[edit]

Critical response[edit]

Chernobyl received widespread critical acclaim. On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the series has an approval rating of 95% based on 103 reviews, with an average rating of 8.9/10. The website's critics consensus reads: "Chernobyl rivets with a creeping dread that never dissipates, dramatizing a national tragedy with sterling craft and an intelligent dissection of institutional rot."[68] On Metacritic, it has a weighted average score of 82 out of 100, based on 27 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[69]

Reviewers for The Atlantic, The Washington Post, and the BBC observed parallels to contemporary society by focusing on the power of information and how dishonest leaders can make mistakes beyond their comprehension.[70] Sophie Gilbert of The Atlantic hailed the series as a "grim disquisition on the toll of devaluing the truth";[71] Hank Stuever of The Washington Post praised it for showcasing "what happens when lying is standard and authority is abused".[72] Meera Syal praised Chernobyl as a "fiercely intelligent exposition of the human cost of state censorship. Would love to see similar exposé of the Bhopal disaster".[73] David Morrison was "struck by the attention to accuracy" and says the "series does an outstanding job of presenting the technical and human issues of the accident."[74]

Jennifer K. Crosby, writing for The Objective Standard, says that the miniseries "explores the reasons for this monumental catastrophe and illustrates how it was magnified by the evasion and denial of those in charge," adding that "although the true toll of the disaster on millions of lives will never be known, Chernobyl goes a long way toward helping us understand [its] real causes and effects."[75] In a negative article titled "Chernobyl: The Show Russiagate wrote," Aaron Giovannone of the American left-wing publication Jacobin wrote that "even as we worry about the ongoing ecological crisis caused by capitalism, Chernobyl revels in the failure of the historical alternative to capitalism, which reinforces the status quo, offering us no way out of the crisis."[76]