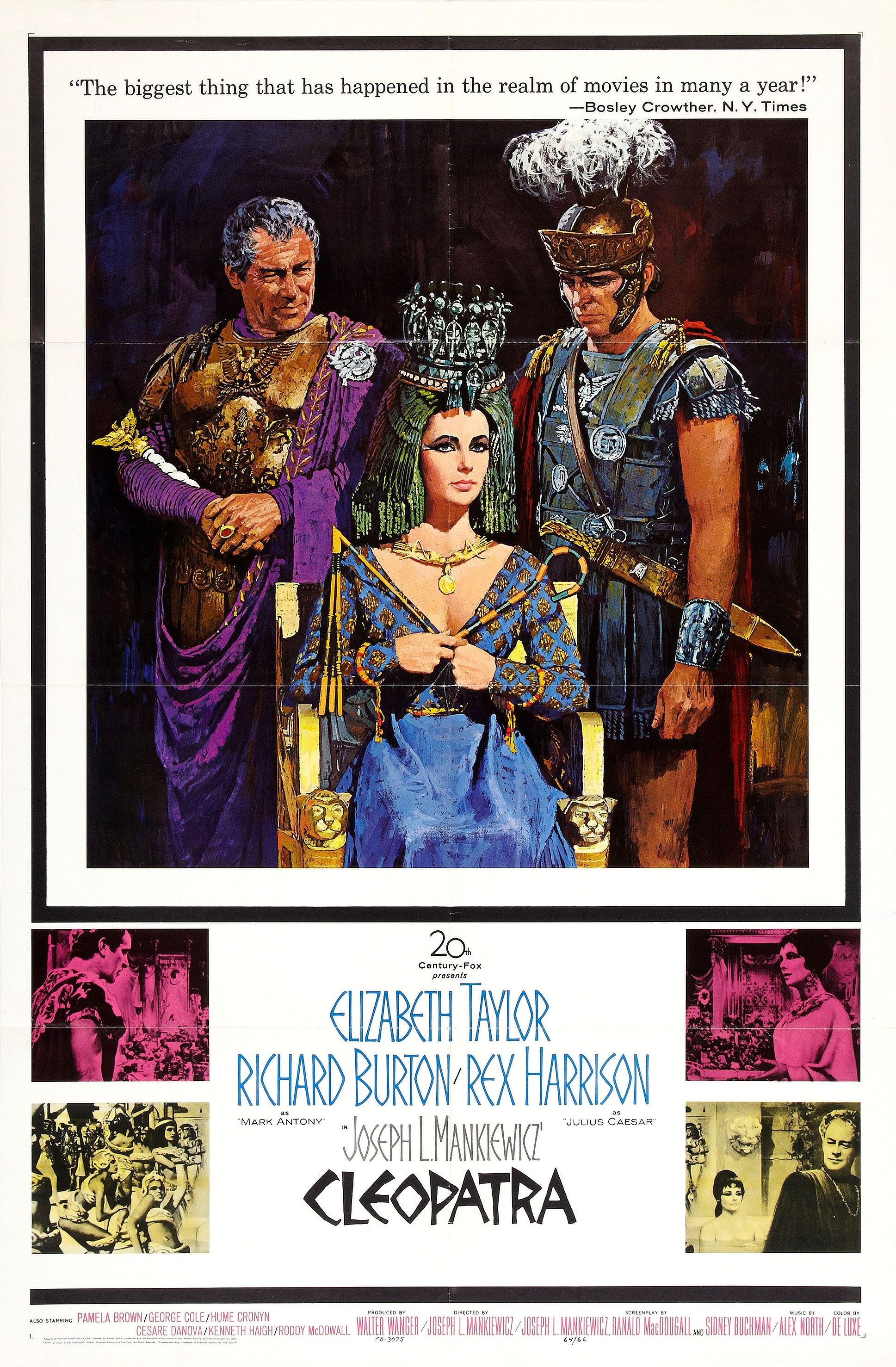

Cleopatra (1963 film)

Cleopatra is a 1963 American epic historical drama film directed by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, with a screenplay adapted by Mankiewicz, Ranald MacDougall and Sidney Buchman from the 1957 book The Life and Times of Cleopatra by Carlo Maria Franzero, and from histories by Plutarch, Suetonius, and Appian. The film stars Elizabeth Taylor in the eponymous role. Richard Burton, Rex Harrison, Roddy McDowall, and Martin Landau also appear in major roles. It chronicles the struggles of Cleopatra, the young queen of Egypt, to resist the imperial ambitions of Rome.

See also: List of cultural depictions of Cleopatra § FilmCleopatra

- Joseph L. Mankiewicz

- Ranald MacDougall

- Sidney Buchman

- June 12, 1963

251 minutes[1]

United States[2]

English

$31.1 million[3]

$57.8 million (US and Canada)

$40.3 million (worldwide theatrical rental)

Walter Wanger had long contemplated producing a biographical film about Cleopatra. In 1958, his production company partnered with Twentieth Century Fox to produce the film. Following an extensive casting search, Elizabeth Taylor signed on to portray the title role for a record-setting salary of $1 million. Rouben Mamoulian was hired as director, and the script underwent numerous revisions from Nigel Balchin, Dale Wasserman, Lawrence Durrell, and Nunnally Johnson. Principal photography began at Pinewood Studios on September 28, 1960, but Taylor's health problems delayed further filming. Production was suspended in November after it had gone overbudget with only ten minutes of usable footage.

Mamoulian resigned as director and was replaced by Mankiewicz, who had directed Taylor in Suddenly, Last Summer (1959). Production was re-located to Cinecittà, where filming resumed on September 25, 1961, without a finished shooting script. During filming, a personal scandal made worldwide headlines when it was reported that co-stars Taylor and Richard Burton had an adulterous affair. Filming wrapped on July 28, 1962, and further reshoots were made from February to March 1963.

With the estimated production costs totaling $31 million (not counting the $5 million spent on the aborted British shoot), the film became the most expensive film ever made up to that point and nearly bankrupted the studio. The cost of distribution, print and advertising expenses added a further $13 million to Fox's costs.

Cleopatra premiered at the Rivoli Theatre in New York City on June 12, 1963. It received a generally favorable response from American film critics, but an unfavorable one in Europe.[4] It became the highest-grossing film of 1963, earning box-office receipts of $57.7 million in the United States and Canada, and one of the highest-grossing films of the decade at a worldwide level. However, the film initially lost money because of its exorbitant production and marketing costs totaling $44 million ($438 million in 2023[5]).

It received nine nominations at the 36th Academy Awards, including for Best Picture, and won four: Best Art Direction (Color), Best Cinematography (Color), Best Visual Effects and Best Costume Design (Color).

Plot[edit]

After the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC, Julius Caesar goes to Egypt, under the pretext of being named the executor of the will of the father of the young Pharaoh Ptolemy XIII and his older sister and co-ruler, Cleopatra. Ptolemy and Cleopatra are in the midst of their own civil war, and she has been driven out of the city of Alexandria. Ptolemy rules alone under the care of his three "guardians": the chief eunuch Pothinus, his tutor Theodotus and General Achillas.

Cleopatra convinces Caesar to restore her throne from Ptolemy. Caesar, in effective control of the kingdom, sentences Pothinus to death for arranging an assassination attempt on Cleopatra, and banishes Ptolemy to the eastern desert, where he and his outnumbered army would face certain death against Mithridates. Cleopatra is crowned queen of Egypt and begins to dream of ruling the world with Caesar, who in turn desires to become king of Rome. They marry, and when their son Caesarion is born, Caesar accepts him publicly, which becomes the talk of Rome and the Senate.

After being made dictator for life, Caesar sends for Cleopatra. She arrives in Rome in a lavish procession and wins the adulation of the Roman people. The Senate grows increasingly discontented amid rumors that Caesar wishes to be made king. On the Ides of March in 44 BC, a group of conspirators assassinate Caesar and flee the city, starting a rebellion. An alliance among Octavian (Caesar's adopted son), Mark Antony (Caesar's right-hand man and general) and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus puts down the rebellion and splits the republic. Cleopatra is angered after Caesar's will recognizes Octavian, rather than Caesarion, as his official heir and returns to Egypt.

While planning a campaign against Parthia in the east, Antony realizes that he needs money and supplies that only Egypt can sufficiently provide. After repeatedly refusing to leave Egypt, Cleopatra acquiesces and meets him on her royal barge in Tarsus. The two begin a love affair. Octavian's removal of Lepidus forces Antony to return to Rome, where he marries Octavian's sister Octavia to prevent political conflict. This enrages Cleopatra. Antony and Cleopatra reconcile and marry, with Antony divorcing Octavia. Octavian, incensed, reads Antony's will to the Roman senate, revealing that Antony wishes to be buried in Egypt. Rome turns against Antony, and Octavian's call for war against Egypt receives a rapturous response. The war is decided at the naval Battle of Actium on September 2, 31 BC, where Octavian's fleet, under the command of Agrippa, defeats the lead ships of the Antony-Egyptian fleet. Assuming Antony is dead, Cleopatra orders the Egyptian forces home. Antony follows her, leaving his fleet leaderless and soon defeated.

Months later, Cleopatra sends Caesarion under disguise out of Alexandria. She also convinces Antony to resume command of his troops and fight Octavian's advancing armies. However, Antony's soldiers abandon him during the night. Rufio, the last man loyal to Antony, kills himself. Antony tries to goad Octavian into single combat, but is eventually forced to flee into the city. When Antony returns to the palace, Apollodorus, who was in love with Cleopatra himself, tells him she is in her tomb as she had instructed, and lets Antony believe she is dead. Antony falls on his own sword. Apollodorus then confesses that he lied to Antony and assists him to the tomb where Cleopatra and two servants had taken refuge. Antony dies in Cleopatra's arms.

Octavian and his army march into Alexandria with Caesarion's dead body in a wagon. He discovers the dead body of Apollodorus, who had poisoned himself. He then receives word that Antony is dead and Cleopatra is holed up in a tomb. There he offers to allow her to rule Egypt as a Roman province if she accompanies him to Rome. Cleopatra, knowing that her son is dead, agrees to Octavian's terms, including a pledge on the life of her son not to harm herself. After Octavian departs, she orders for her servants to assist with her suicide. Discovering that she was going to kill herself, Octavian and his guards burst into Cleopatra's chamber to find her dead, dressed in gold, along with her servants and the asp that killed her.

Reception[edit]

Critical response[edit]

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called Cleopatra "one of the great epic films of our day," crediting Mankiewicz for "his fabrication of characters of colorfulness and depth, who stand forth as thinking, throbbing people against a background of splendid spectacle, that gives vitality to this picture and is the key to its success."[110] Vincent Canby, reviewing for Variety, wrote that Cleopatra is "not only a supercolossal eye-filler (the unprecedented budget shows in the physical opulence throughout), but it is also a remarkably literate cinematic recreation of an historic epoch."[111] For the Los Angeles Times, Philip K. Scheuer felt Cleopatra was "a surpassingly beautiful film and a drama that need not hide its literate, intelligent face because it happens to have been written, not by Shakespeare or Shaw, but by three fellows named Joseph L. Mankiewicz, who also directed it, Ranald MacDougall and Sidney Buchman. These are, at any rate, the names on the screen credits, and they have done their job with integrity."[112]

Time magazine harshly wrote: "As drama and as cinema, Cleopatra is riddled with flaws. It lacks style both in image and in action. Never for an instant does it whirl along on wings of epic elan; generally it just bumps from scene to ponderous scene on the square wheels of exposition."[113] James Powers of The Hollywood Reporter wrote "Cleopatra is not a great movie. But it is primarily a vast, popular entertainment that sidesteps total greatness for broader appeal. This is not an adverse criticism, but a notation of achievement."[114] Claudia Cassidy of the Chicago Tribune summarized Cleopatra as a "huge and disappointing film." Of the cast, she lauded "Rex Harrison's brilliantly quizzical Caesar, the best written role in Joseph Mankiewicz's erratic script, and haunted by Richard Burton's tragic Marc Antony, an actor's triumph over a writer's mediocrity. And with a prodigal gesture of futility, all of it is focused on Elizabeth Taylor, hopelessly out of her depth as a fishwife Cleopatra."[115]

Penelope Houston, reviewing for Sight & Sound, acknowledged that Mankiewicz tried "to make this a film about people and their emotions rather than a series of sideshows. But for this ambition to hold up, over the film's great footage, he needed a visual style which would be more than merely illustrative, dialogue really worth speaking, and actors altogether more persuasive. As the sets seem to grow bigger and bigger, so progressively the actors dwindle."[116] Judith Crist, in her review for the New York Herald Tribune, concurred: "So grand and grandiose are the sets that the characters are dwarfed, and so wide is his screen that this concentration on character results in a strangely static epic in which the overblown close-ups are interrupted at best by a pageant or dance, more often by unexciting bits and pieces of exits, entrances, marches or battles."[117] Even Elizabeth Taylor found it wanting, saying, "They had cut out the heart, the essence, the motivations, the very core, and tacked on all those battle scenes. It should have been about three large people, but it lacked reality and passion. I found it vulgar."[118]

At the time of the film's release, The New York Times estimated that 80 percent of film reviews in the United States were favorable but only 20 percent in Europe were positive.[4] Among contemporary reviews, American film critic Emanuel Levy wrote retrospectively: "Much maligned for various reasons, [...] Cleopatra may be the most expensive movie ever made, but certainly not the worst, just a verbose, muddled affair that is not even entertaining as a star vehicle for Taylor and Burton."[119] Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian wrote the film is "a stately but sometimes mindboggling spectacle. This restored big-screen version shouldn't be missed: it's a colossus of the analogue-epic era, and the high point of Elizabeth Taylor's global celebrity, when her prestige was hardly less towering than that of the actual queen of the Nile."[120] Billy Mowbray of British television channel Film4 remarked that the film is "[a] giant of a movie that is sometimes lumbering, but ever watchable thanks to its uninhibited ambition, size and glamour."[121]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 56% of 43 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 5.9/10. The website's consensus reads: "Cleopatra is a lush, ostentatious, endlessly eye-popping epic that sags [and] collapses from a (and how could it not?) four-hour runtime."[122] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 60 out of 100, based on 14 critics, indicating "mixed or average" reviews.[123]

Box office[edit]

Three weeks into its theatrical release, Cleopatra became the number-one box office film in the United States, grossing $725,000 in 17 key cities.[124] It held the top position for the next twelve weeks before being dethroned by The V.I.P.s, which also starred Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. It recaptured the number-one spot three weeks later,[125] and proved to be the highest-grossing film of 1963.[126] By January 1964, the film had earned $15.7 million in distributor rentals from 55 theaters in the United States and Canada.[127][128] It finished its box-office run with $26 million in rentals in the United States and Canada.[129] The film was also a major hit in Italy, where it sold 10.9 million tickets.[130] It sold a further 5.4 million tickets in France and Germany,[130] and 32.9 million tickets in the Soviet Union when it was released there in 1978.[131]

By March 1966, Cleopatra had earned worldwide rentals of $38.04 million, leaving it $3 million short of breaking even.[132] Fox eventually recouped its investment that same year when it sold the television broadcast rights to ABC for $5 million,[133] a then-record amount paid for a single film.[134] The film ultimately earned $40.3 million in worldwide rentals from its theatrical run.[133]