The defining characteristic of common law is that it arises as precedent. Common law courts look to the past decisions of courts to synthesize the legal principles of past cases. Stare decisis, the principle that cases should be decided according to consistent principled rules so that similar facts will yield similar results, lies at the heart of all common law systems.[5] If a court finds that a similar dispute to the present one has been resolved in the past, the court is generally bound to follow the reasoning used in the prior decision. If, however, the court finds that the current dispute is fundamentally distinct from all previous cases (a "matter of first impression"), and legislative statutes (also called "positive law") are either silent or ambiguous on the question, judges have the authority and duty to resolve the issue.[6] The opinion from a common law judge agglomerates with past decisions as precedent to bind future judges and litigants, unless overturned by further developments in the law or by subsequent statutory law.

The common law, so named because it was "common" to all the king's courts across England, originated in the practices of the courts of the English kings in the centuries following the Norman Conquest in 1066.[7] The British Empire later spread the English legal system to its colonies, many of which retain the common law system today. These common law systems are legal systems that give great weight to judicial precedent, and to the style of reasoning inherited from the English legal system.[8][9][10][11]

The term "common law", referring to the body of law made by the judiciary,[4][12] is often distinguished from statutory law and regulations, which are laws adopted by the legislature and executive respectively. In legal systems that follow the common law, judicial precedent stands in contrast to and on equal footing with statutes. The other major legal system used by countries is the civil law, which codifies its legal principles into legal codes and does not treat judicial opinions as binding.

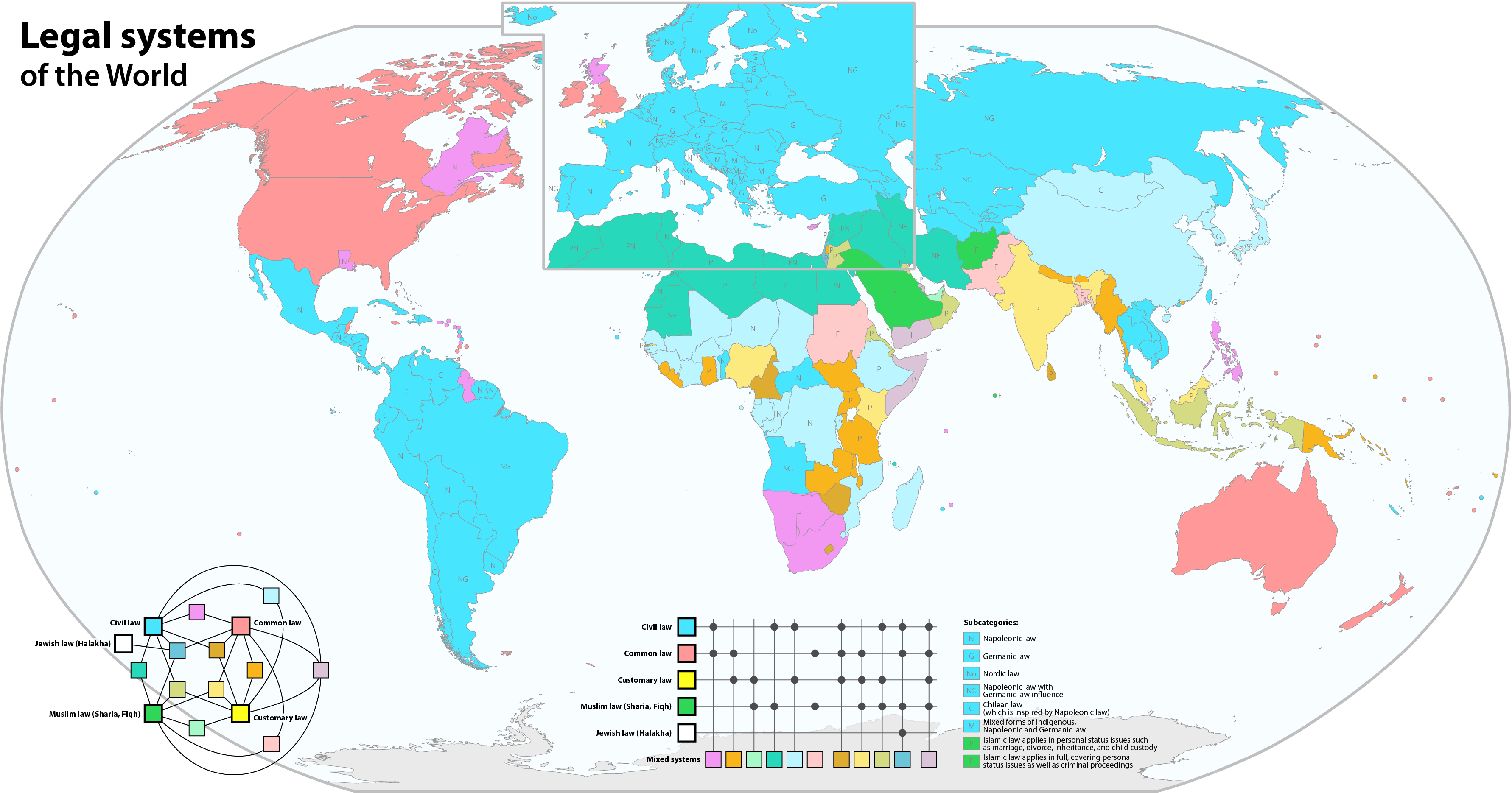

Today, one-third of the world's population lives in common law jurisdictions or in mixed legal systems that combine the common law with the civil law, including[13]

Antigua and Barbuda, Australia,[14][15] The Bahamas, Bangladesh, Barbados,[16] Belize, Botswana, Burma, Cameroon, Canada (both the federal system and all its provinces except Quebec), Cyprus, Dominica, Fiji, Ghana, Grenada, Guyana, Hong Kong, India, Ireland, Israel, Jamaica, Kenya, Liberia, Malaysia, Malta, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Namibia, Nauru, New Zealand, Nigeria, Pakistan, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Sierra Leone, Singapore, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Trinidad and Tobago, the United Kingdom (including its overseas territories such as Gibraltar), the United States (both the federal system and 49 of its 50 states), and Zimbabwe.

Basic principles of common law[edit]

Common law adjudication[edit]

In a common law jurisdiction several stages of research and analysis are required to determine "what the law is" in a given situation.[23] First, one must ascertain the facts. Then, one must locate any relevant statutes and cases. Then one must extract the principles, analogies and statements by various courts of what they consider important to determine how the next court is likely to rule on the facts of the present case. More recent decisions, and decisions of higher courts or legislatures carry more weight than earlier cases and those of lower courts.[24] Finally, one integrates all the lines drawn and reasons given, and determines "what the law is". Then, one applies that law to the facts.

In practice, common law systems are considerably more complicated than the simplified system described above. The decisions of a court are binding only in a particular jurisdiction, and even within a given jurisdiction, some courts have more power than others. For example, in most jurisdictions, decisions by appellate courts are binding on lower courts in the same jurisdiction, and on future decisions of the same appellate court, but decisions of lower courts are only non-binding persuasive authority. Interactions between common law, constitutional law, statutory law and regulatory law also give rise to considerable complexity.