Continental shelf

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island is known as an insular shelf.

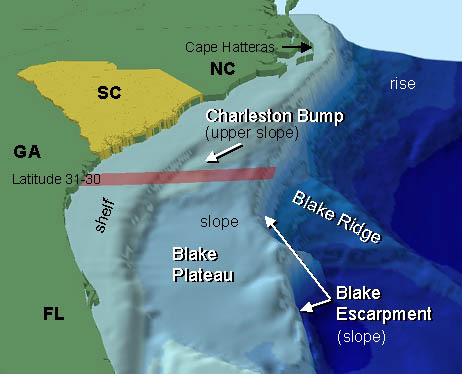

The continental margin, between the continental shelf and the abyssal plain, comprises a steep continental slope, surrounded by the flatter continental rise, in which sediment from the continent above cascades down the slope and accumulates as a pile of sediment at the base of the slope. Extending as far as 500 km (310 mi) from the slope, it consists of thick sediments deposited by turbidity currents from the shelf and slope.[1][2] The continental rise's gradient is intermediate between the gradients of the slope and the shelf.

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the name continental shelf was given a legal definition as the stretch of the seabed adjacent to the shores of a particular country to which it belongs.

Sediments[edit]

The continental shelves are covered by terrigenous sediments; that is, those derived from erosion of the continents. However, little of the sediment is from current rivers; some 60–70% of the sediment on the world's shelves is relict sediment, deposited during the last ice age, when sea level was 100–120 m lower than it is now.[21][11]

Sediments usually become increasingly fine with distance from the coast; sand is limited to shallow, wave-agitated waters, while silt and clays are deposited in quieter, deep water far offshore.[22] These accumulate 15–40 centimetres (5.9–15.7 in) every millennium, much faster than deep-sea pelagic sediments.[23]

"Shelf seas" are the ocean waters on the continental shelf. Their motion is controlled by the combined influences of the tides, wind-forcing and brackish water formed from river inflows (Regions of Freshwater Influence). These regions can often be biologically highly productive due to mixing caused by the shallower waters and the enhanced current speeds. Despite covering only about 8% of Earth's ocean surface area,[20] shelf seas support 15–20% of global primary productivity.[24]

In temperate continental shelf seas, three distinctive oceanographic regimes are found, as a consequence of the interplay between surface heating, lateral buoyancy gradients (due to river inflow), and turbulent mixing by the tides and to a lesser extent the wind.[25]

Indian Ocean shelf seas are dominated by major river systems, including the Ganges and Indus rivers.[30] The shelf seas around New Zealand are complicated because the submerged continent of Zealandia creates wide plateaus.[31] Shelf seas around Antarctica and the shores of the Arctic Ocean are influenced by sea ice production and polynya.[32]

There is evidence that changing wind, rainfall, and regional ocean currents in a warming ocean are having an effect on some shelf seas.[33] Improved data collection via Integrated Ocean Observing Systems in shelf sea regions is making identification of these changes possible.[34]

Biota[edit]

Continental shelves teem with life because of the sunlight available in shallow waters, in contrast to the biotic desert of the oceans' abyssal plain. The pelagic (water column) environment of the continental shelf constitutes the neritic zone, and the benthic (sea floor) province of the shelf is the sublittoral zone.[35] The shelves make up less than 10% of the ocean, and a rough estimate suggests that only about 30% of the continental shelf sea floor receives enough sunlight to allow benthic photosynthesis.[36]

Though the shelves are usually fertile, if anoxic conditions prevail during sedimentation, the deposits may over geologic time become sources for fossil fuels.[37][38]