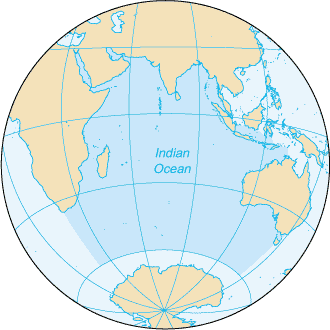

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering 70,560,000 km2 (27,240,000 sq mi) or approx. 20% of the water on Earth's surface.[4] It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by the Southern Ocean, or Antarctica, depending on the definition in use.[5] Along its core, the Indian Ocean has large marginal, or regional seas, such as the Andaman Sea, the Arabian Sea, the Bay of Bengal, and the Laccadive Sea.

For the rock band, see Indian Ocean (band).Indian Ocean

21,100,000 km2 (8,100,000 sq mi)

South and Southeast Asia, Western Asia, Northeast, East and Southern Africa and Australia

9,600 km (6,000 mi)

(Antarctica to Bay of Bengal)[1]

7,600 km (4,700 mi)

(Africa to Australia)[1]

70,560,000 km2 (27,240,000 sq mi)

3,741 m (12,274 ft)

7,290 m (23,920 ft)

(Sunda Trench)

66,526 km (41,337 mi)[2]

It is named after India, which protrudes into it, and has been known by its current name since at least 1515. Previously, it was called the Eastern Ocean. It has an average depth of 3,741 m. All of the Indian Ocean is in the Eastern Hemisphere. Unlike the Atlantic and Pacific, the Indian Ocean is bordered by landmasses and an archipelago on three sides, making it more like an embayed ocean centered on the Indian Peninsula. Its coasts and shelves differ from other oceans, with distinct features, such as a narrower continental shelf. In terms of geology, the Indian Ocean is the youngest of the major oceans, with active spreading ridges and features like seamounts and ridges formed by hotspots.

The climate of the Indian Ocean is characterized by monsoons. It is the warmest ocean, with a significant impact on global climate due to its interaction with the atmosphere. Its waters are affected by the Indian Ocean Walker circulation, resulting in unique oceanic currents and upwelling patterns. The Indian Ocean is ecologically diverse, with important marine life and ecosystems like coral reefs, mangroves, and sea grass beds. It hosts a significant portion of the world's tuna catch and is home to endangered marine species. It faces challenges like overfishing and pollution, including a significant garbage patch.

Historically, the Indian Ocean has been a hub of cultural and commercial exchange since ancient times. It played a key role in early human migrations and the spread of civilizations. In modern times, it remains crucial for global trade, especially in oil and hydrocarbons. Environmental and geopolitical concerns in the region include the effects of climate change, piracy, and strategic disputes over island territories.

Etymology[edit]

The Indian Ocean has been known by its present name since at least 1515, when the Latin form Oceanus Orientalis Indicus ("Indian Eastern Ocean") is attested, named after India, which projects into it. It was earlier known as the Eastern Ocean, a term that was still in use during the mid-18th century, as opposed to the Western Ocean (Atlantic) before the Pacific was surmised.[6] In modern times, the name Afro-Asian Ocean has occasionally been used.[7]

The Hindi name for the Ocean is हिंद महासागर (Hind Mahāsāgar; lit. transl. Ocean of India). Conversely, Chinese explorers (e.g., Zheng He during the Ming dynasty) who traveled to the Indian Ocean during the 15th century called it the Western Oceans.[8] In Ancient Greek geography, the Indian Ocean region known to the Greeks was called the Erythraean Sea.[9]

Oceanography[edit]

Forty percent of the sediment of the Indian Ocean is found in the Indus and Ganges fans. The oceanic basins adjacent to the continental slopes mostly contain terrigenous sediments. The ocean south of the polar front (roughly 50° south latitude) is high in biologic productivity and dominated by non-stratified sediment composed mostly of siliceous oozes. Near the three major mid-ocean ridges the ocean floor is relatively young and therefore bare of sediment, except for the Southwest Indian Ridge due to its ultra-slow spreading rate.[28]

The ocean's currents are mainly controlled by the monsoon. Two large gyres, one in the northern hemisphere flowing clockwise and one south of the equator moving anticlockwise (including the Agulhas Current and Agulhas Return Current), constitute the dominant flow pattern. During the winter monsoon (November–February), however, circulation is reversed north of 30°S and winds are weakened during winter and the transitional periods between the monsoons.[29]

The Indian Ocean contains the largest submarine fans of the world, the Bengal Fan and Indus Fan, and the largest areas of slope terraces and rift valleys.

[30]

The inflow of deep water into the Indian Ocean is 11 Sv, most of which comes from the Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW). The CDW enters the Indian Ocean through the Crozet and Madagascar basins and crosses the Southwest Indian Ridge at 30°S. In the Mascarene Basin the CDW becomes a deep western boundary current before it is met by a re-circulated branch of itself, the North Indian Deep Water. This mixed water partly flows north into the Somali Basin whilst most of it flows clockwise in the Mascarene Basin where an oscillating flow is produced by Rossby waves.[31]

Water circulation in the Indian Ocean is dominated by the Subtropical Anticyclonic Gyre, the eastern extension of which is blocked by the Southeast Indian Ridge and the 90°E Ridge. Madagascar and the Southwest Indian Ridge separate three cells south of Madagascar and off South Africa. North Atlantic Deep Water reaches into the Indian Ocean south of Africa at a depth of 2,000–3,000 m (6,600–9,800 ft) and flows north along the eastern continental slope of Africa. Deeper than NADW, Antarctic Bottom Water flows from Enderby Basin to Agulhas Basin across deep channels (<4,000 m (13,000 ft)) in the Southwest Indian Ridge, from where it continues into the Mozambique Channel and Prince Edward Fracture Zone.[32]

North of 20° south latitude the minimum surface temperature is 22 °C (72 °F), exceeding 28 °C (82 °F) to the east. Southward of 40° south latitude, temperatures drop quickly.[22]

The Bay of Bengal contributes more than half (2,950 km3 or 710 cu mi) of the runoff water to the Indian Ocean. Mainly in summer, this runoff flows into the Arabian Sea but also south across the Equator where it mixes with fresher seawater from the Indonesian Throughflow. This mixed freshwater joins the South Equatorial Current in the southern tropical Indian Ocean.[33]

Sea surface salinity is highest (more than 36 PSU) in the Arabian Sea because evaporation exceeds precipitation there. In the Southeast Arabian Sea salinity drops to less than 34 PSU. It is the lowest (c. 33 PSU) in the Bay of Bengal because of river runoff and precipitation. The Indonesian Throughflow and precipitation results in lower salinity (34 PSU) along the Sumatran west coast. Monsoonal variation results in eastward transportation of saltier water from the Arabian Sea to the Bay of Bengal from June to September and in westerly transport by the East India Coastal Current to the Arabian Sea from January to April.[34]

An Indian Ocean garbage patch was discovered in 2010 covering at least 5 million square kilometres (1.9 million square miles). Riding the southern Indian Ocean Gyre, this vortex of plastic garbage constantly circulates the ocean from Australia to Africa, down the Mozambique Channel, and back to Australia in a period of six years, except for debris that gets indefinitely stuck in the centre of the gyre.[35]

The garbage patch in the Indian Ocean will, according to a 2012 study, decrease in size after several decades to vanish completely over centuries. Over several millennia, however, the global system of garbage patches will accumulate in the North Pacific.[36]

There are two amphidromes of opposite rotation in the Indian Ocean, probably caused by Rossby wave propagation.[37]

Icebergs drift as far north as 55° south latitude, similar to the Pacific but less than in the Atlantic where icebergs reach up to 45°S. The volume of iceberg loss in the Indian Ocean between 2004 and 2012 was 24 Gt.[38]

Since the 1960s, anthropogenic warming of the global ocean combined with contributions of freshwater from retreating land ice causes a global rise in sea level. Sea level also increases in the Indian Ocean, except in the south tropical Indian Ocean where it decreases, a pattern most likely caused by rising levels of greenhouse gases.[39]

Of Earth's 36 biodiversity hotspots nine (or 25%) are located on the margins of the Indian Ocean.

The origin of this diversity is debated; the break-up of Gondwana can explain vicariance older than 100 mya, but the diversity on the younger, smaller islands must have required a Cenozoic dispersal from the rims of the Indian Ocean to the islands. A "reverse colonisation", from islands to continents, apparently occurred more recently; the chameleons, for example, first diversified on Madagascar and then colonised Africa. Several species on the islands of the Indian Ocean are textbook cases of evolutionary processes; the dung beetles,[49][50] day geckos,[51][52] and lemurs are all examples of adaptive radiation.[53]

Many bones (250 bones per square metre) of recently extinct vertebrates have been found in the Mare aux Songes swamp in Mauritius, including bones of the Dodo bird (Raphus cucullatus) and Cylindraspis giant tortoise. An analysis of these remains suggests a process of aridification began in the southwest Indian Ocean began around 4,000 years ago.[54]

Mammalian megafauna once widespread in the MPA was driven to near extinction in the early 20th century. Some species have been successfully recovered since then — the population of white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum simum) increased from less than 20 individuals in 1895 to more than 17,000 as of 2013. Other species still depend on fenced areas and management programs, including black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis minor), African wild dog (Lycaon pictus), cheetah (Acynonix jubatus), elephant (Loxodonta africana), and lion (Panthera leo).[55]

This biodiversity hotspot (and namesake ecoregion and "Endemic Bird Area") is a patchwork of small forested areas, often with a unique assemblage of species within each, located within 200 km (120 mi) from the coast and covering a total area of c. 6,200 km2 (2,400 sq mi). It also encompasses coastal islands, including Zanzibar and Pemba, and Mafia.[56]

This area, one of the only two hotspots that are entirely arid, includes the Ethiopian Highlands, the East African Rift valley, the Socotra islands, as well as some small islands in the Red Sea and areas on the southern Arabic Peninsula. Endemic and threatened mammals include the dibatag (Ammodorcas clarkei) and Speke's gazelle (Gazella spekei); the Somali wild ass (Equus africanus somaliensis) and hamadryas baboon (Papio hamadryas). It also contains many reptiles.[57]

In Somalia, the centre of the 1,500,000 km2 (580,000 sq mi) hotspot, the landscape is dominated by Acacia-Commiphora deciduous bushland, but also includes the Yeheb nut (Cordeauxia edulus) and species discovered more recently such as the Somali cyclamen (Cyclamen somalense), the only cyclamen outside the Mediterranean. Warsangli linnet (Carduelis johannis) is an endemic bird found only in northern Somalia. An unstable political situation and mismanagement has resulted in overgrazing which has produced one of the most degraded hotspots where only c. 5 % of the original habitat remains.[58]

Encompassing the west coast of India and Sri Lanka, until c. 10,000 years ago a landbridge connected Sri Lanka to the Indian Subcontinent, hence this region shares a common community of species.[59]

Indo-Burma encompasses a series of mountain ranges, five of Asia's largest river systems, and a wide range of habitats. The region has a long and complex geological history, and long periods rising sea levels and glaciations have isolated ecosystems and thus promoted a high degree of endemism and speciation. The region includes two centres of endemism: the Annamite Mountains and the northern highlands on the China-Vietnam border.[60]

Several distinct floristic regions, the Indian, Malesian, Sino-Himalayan, and Indochinese regions, meet in a unique way in Indo-Burma and the hotspot contains an estimated 15,000–25,000 species of vascular plants, many of them endemic.[61]

Sundaland encompasses 17,000 islands of which Borneo and Sumatra are the largest. Endangered mammals include the Bornean and Sumatran orangutans, the proboscis monkey, and the Javan and Sumatran rhinoceroses.[62]

Stretching from Shark Bay to Israelite Bay and isolated by the arid Nullarbor Plain, the southwestern corner of Australia is a floristic region with a stable climate in which one of the world's largest floral biodiversity and an 80% endemism has evolved. From June to September it is an explosion of colours and the Wildflower Festival in Perth in September attracts more than half a million visitors.[63]