Day for Night (film)

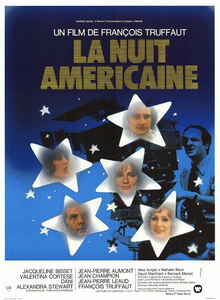

Day for Night (French: La Nuit américaine, lit. 'American Night') is a 1973 romantic comedy-drama film co-written and directed by François Truffaut. The metafictional and self-reflexive film chronicles the troubled production of a melodrama, and the various personal and professional challenges of the cast and crew. It stars Jacqueline Bisset, Valentina Cortese, Jean-Pierre Aumont, Dani, Alexandra Stewart, Jean-Pierre Léaud and Truffaut himself.[4]

Day for Night

La Nuit américaine

American Night

- François Truffaut

- Jean-Louis Richard

- Suzanne Schiffman

Marcel Berbert

- Yann Dedet

- Martine Barraquè

- Les Films du Carrosse

- PECF

- PIC

- 14 May 1973 (Cannes)

- 24 May 1973 (France)

- 7 September 1973 (Italy)

116 minutes

French

$700,000[2]

839,583 admissions (France)[3]

The film premiered out of competition at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival and won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film the following year.[5] At the 1975 Oscars, the film was nominated for Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Supporting Actress for Valentina Cortese. The film also won three BAFTA Awards, for Best Film, Best Direction, and Best Actress in a Supporting Role for Cortese.

Retrospective reviews have appraised Day for Night as one of Truffaut's best films, and one of the greatest films of all time.[6][7]

Title[edit]

The original French title, La Nuit américaine, refers to the French name for the filmmaking process whereby sequences filmed outdoors in daylight are shot with a filter over the camera lens (a technique described in the dialogue of Truffaut's film) or also using film stock balanced for tungsten (indoor) light and underexposed (or adjusted during post-production) to appear as if they are taking place at night. In English, the technique is called day for night.

Plot[edit]

The film chronicles the production of Je Vous Présente Paméla (Meet Pamela, or literally I Introduce You to Pamela), a clichéd melodrama starring aging screen icon Alexandre, former Italian diva Séverine, young heartthrob Alphonse and British actress Julie Baker, who is recovering from both a nervous breakdown and the controversy over her marriage to her much older doctor.

In between are several vignettes chronicling the stories of the crew members and the director, Ferrand, who deals with the practical problems of making a film. Behind the camera, the actors and crew experience several romances, affairs, break-ups and sorrows. The production is especially shaken up when one of the supporting actresses is revealed to be pregnant.

Later, Alphonse's lover leaves him for the film's stuntman, which leads Alphonse into a palliative one-night stand with an accommodating Julie; thereupon, mistaking Julie's pity for true love, the infantile Alphonse informs Julie's husband of the affair. Finally, Alexandre dies on the way to hospital after a car accident.

Themes[edit]

One of the film's themes is whether cinema is more important than life to those who make it. It makes many allusions both to filmmaking and to movies themselves, perhaps unsurprisingly since Truffaut began his career as a film critic who championed cinema as an art form. The film opens with a picture of Lillian and Dorothy Gish, to whom it is dedicated. In one scene, Ferrand opens a package of books he has ordered on directors such as Luis Buñuel, Carl Theodor Dreyer, Ingmar Bergman, Alfred Hitchcock, Howard Hawks, Jean-Luc Godard, Ernst Lubitsch, Roberto Rossellini and Robert Bresson.

The film's French title could sound like L'ennui américain ("American boredom"): Truffaut wrote elsewhere of the way French cinema critics inevitably make this pun of any title that uses nuit. Here, he deliberately invites his viewers to recognise the artificiality of cinema, particularly American-style studio film, with its reliance on effects such as day for night, that Je Vous Présente Paméla exemplifies.[8]

Reception[edit]

Critical response[edit]

The film is often considered one of Truffaut's best. It is one of two Truffaut films on Time magazine's list of the 100 Best Films of the Century, along with The 400 Blows (1959).[6] It has also been called "the most beloved film ever made about filmmaking".[7]

Roger Ebert gave the film four stars out of four, writing, "it is not only the best movie ever made about the movies but is also a great entertainment."[15] He added it to his "The Great Movies" list in 1997.[16] Vincent Canby of The New York Times called the film "hilarious, wise and moving," with "superb" performances.[17] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film four stars out of four, calling it "a movie about the making of a movie; it also is a wonderfully tender story of the fragile, funny, and tough people who populate the film business."[18] He named it the best film of 1973 in his year-end list.[19] Pauline Kael of The New Yorker called the film "a return to form" for Truffaut, "though it's a return only to form." She added, "It has a pretty touch. But when it was over, I found myself thinking, Can this be all there is to it? The picture has no center and not much spirit."[20] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times called it "one of the most sheerly enjoyable movies of any year, for any audience. For those who love the movies as Truffault loves them, 'Day for Night' is a very special testament of that love."[21] Richard Combs of The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote, "Easily classifiable as a lightweight work, and never digging much below the surface of either its characters or its director's particular concept of cinema, the film still manages to be an irresistable [sic?] delight simply because of the élan and ingenious craftsmanship with which its traditionally dangerous, self-conscious format is handled."[22] On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 98% based on 40 reviews, with an average score of 8.50/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "A sweet counterpoint to Godard's Contempt, Truffaut's Day for Night is a congenial tribute to the self-afflicted madness that is making a movie".[23]

Jean-Luc Godard walked out of Day for Night in disgust, and accused Truffaut of making a film that was a "lie". Truffaut responded with a long letter critical of Godard, and the two former friends never met again.[24]