Various legal systems and government agencies use different definitions of terrorism, and governments have been reluctant to formulate an agreed-upon legally-binding definition. Difficulties arise from the fact that the term has become politically and emotionally charged.[4][5] A simple definition proposed to the United Nations Commission on Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice (CCPCJ) by terrorism studies scholar Alex P. Schmid in 1992, based on the already internationally accepted definition of war crimes, as "peacetime equivalents of war crimes",[6] was not accepted.[7][8]

Scholars have worked on creating various academic definitions, reaching a consensus definition published by Schmid and A. J. Jongman in 1988, with a longer revised version published by Schmid in 2011,[8] some years after he had written that "the price for consensus [had] led to a reduction of complexity".[9] The Cambridge History of Terrorism (2021), however, states that Schmid's "consensus" resembles an intersection of definitions, rather than a bona fide consensus.[10]

The United Nations General Assembly condemned terrorist acts by using the following political description of terrorism in December 1994 (GA Res. 49/60):[11]

Definitions include:

Bruce Hoffman notes that terrorism is "ineluctably about power".[24]

Terrorism has been described as:

Definitions of terrorism typically emphasize one or more of the following features:[19]

The following criteria of violence or threat of violence usually fall outside of the definition of terrorism:[25][26]

Scholar Ken Duncan argues the term terrorism has generally been used to describe violence by non-state actors rather than government violence since the 19th-century Anarchist Movement.[27][28][29]

In international law[edit]

The need to define terrorism in international criminal law[edit]

Schmid (2004) summarised many sources when he wrote: "It is widely agreed that international terrorism can only be fought by international cooperation". If states do not agree on what constitutes terrorism, the chances of cooperation between countries is reduced; for example, agreement is needed so that extradition is possible.[9]

Ben Saul has noted (2008): "A combination of pragmatic and principled arguments supports the case for defining terrorism in international law". Reasons for why terrorism needs to be defined by the international community include the need to condemn violations to human rights; to protect the state and its constitutional order, which protects rights; to differentiate public and private violence; to ensure international peace and security, and "control the operation of mandatory Security Council measures since 2001".[30]

Carlos Diaz-Paniagua, who coordinated the negotiations of the proposed United Nations Comprehensive Convention on International Terrorism (proposed in 1996 and not yet achieved), noted in 2008 the need to provide a precise definition of terrorist activities in international law: "Criminal law has three purposes: to declare that a conduct is forbidden, to prevent it, and to express society's condemnation for the wrongful acts. The symbolic, normative role of criminalization is of particular importance in the case of terrorism. The criminalization of terrorist acts expresses society's repugnance at them, invokes social censure and shame, and stigmatizes those who commit them. Moreover, by creating and reaffirming values, criminalization may serve, in the long run, as a deterrent to terrorism, as those values are internalized." Thus, international criminal law treaties that seek to prevent, condemn and punish terrorist activities, require precise definitions:[31]

In national law[edit]

Australia[edit]

As of April 2021, the Criminal Code Act 1995 (known as the Criminal Code), representing the federal government's criminal law and including Australia's laws against terrorism, defines "terrorist act" in Section 5.3.[78] The definition, after defining in (a) the harms that may be caused (and excluding accidental harm or various actions undertaken as advocacy) defines a terrorist act as:[79]

After the September 11 terrorist attacks in the U.S., many insurers made specific exclusions for terrorism in their policies, after global reinsurers withdrew from covering terrorism. Some governments introduced legislation to provide support for insurers in various ways.[105][106]

Some insurance companies exclude terrorism from general property insurance. An insurance company may include a specific definition of terrorism as part of its policy, for the purpose of excluding at least some loss or damage caused by terrorism. For example, RAC Insurance in Western Australia defines terrorism thus:[110]

It is noted the term Stochastic terrorism began as a method to corelate measurements of violent rhetoric to probability of a terrorists attack.[111][112] While this term is still used in the technical sense in risk management and insurance assessments, a more populist connotation has developed that is used to characterize the nature of certain terrorist acts in the context of social media influence.[113]

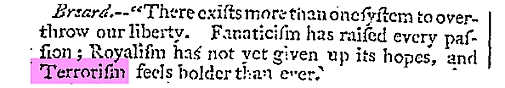

Listed below are some of the historically important understandings of terror and terrorism, and enacted but non-universal definitions of the term: