Terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of intentional violence and fear to achieve political or ideological aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violence during peacetime or in the context of war against non-combatants (mostly civilians and neutral military personnel).[1] There are various different definitions of terrorism, with no universal agreement about it.[2][3]

"Terrorist" redirects here. For other uses, see Terrorist (disambiguation).

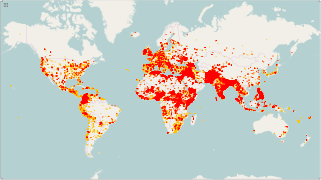

The terms "terrorist" and "terrorism" originated during the French Revolution of the late 18th century[4] but became widely used internationally and gained worldwide attention in the 1970s during the Troubles in Northern Ireland, the Basque conflict and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. The increased use of suicide attacks from the 1980s onwards was typified by the 2001 September 11 attacks in the United States. The Global Terrorism Database, maintained by the University of Maryland, College Park, has recorded more than 61,000 incidents of non-state terrorism, resulting in at least 140,000 deaths, between 2000 and 2014.[5]

Varied political organizations have been accused of using terrorism to achieve their objectives. These include left-wing and right-wing political organizations, nationalist groups, religious groups, revolutionaries, and ruling governments.[6]

Terrorism is a charged term. It is often used with the connotation of something that is "morally wrong". Governments and non-state groups use the term to abuse or denounce opposing groups.[3][7][8][9][10] While legislation defining terrorism as a crime has been adopted in many states, the distinction between activism and terrorism remains a complex and debated matter.[11][12] There is no consensus as to whether terrorism should be regarded as a war crime.[11][13] State terrorism is that perpetrated by nation states, but is not considered such by the state conducting it, making legality a grey area.[14]

Depending on the country, the political system, and the time in history, the types of terrorism are varying.

In early 1975, the Law Enforcement Assistant Administration in the United States formed the National Advisory Committee on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals. One of the five volumes that the committee wrote was titled Disorders and Terrorism, produced by the Task Force on Disorders and Terrorism under the direction of H. H. A. Cooper, Director of the Task Force staff.

The Task Force defines terrorism as "a tactic or technique by means of which a violent act or the threat thereof is used for the prime purpose of creating overwhelming fear for coercive purposes". It classified disorders and terrorism into seven categories:[99]

Other sources have defined the typology of terrorism in different ways, for example, broadly classifying it into domestic terrorism and international terrorism, or using categories such as vigilante terrorism or insurgent terrorism.[102] Some ways the typology of terrorism may be defined are:[103][104]

Democracy and domestic terrorism

Terrorism is most common in nations with intermediate political freedom, and it is least common in the most democratic nations.[115][116][117][118]

Some examples of "terrorism" in non-democratic nations include ETA in Spain under Francisco Franco (although the group's activities increased sharply after Franco's death),[119] the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists in pre-war Poland,[120] the Shining Path in Peru under Alberto Fujimori,[121] the Kurdistan Workers Party when Turkey was ruled by military leaders and the ANC in South Africa.[122] Democracies, such as Japan, the United Kingdom, the United States, Israel, Indonesia, India, Spain, Germany, Italy and the Philippines, have experienced domestic terrorism.

While a democratic nation espousing civil liberties may claim a sense of higher moral ground than other regimes, an act of terrorism within such a state may cause a dilemma: whether to maintain its civil liberties and thus risk being perceived as ineffective in dealing with the problem; or alternatively to restrict its civil liberties and thus risk delegitimizing its claim of supporting civil liberties.[123] For this reason, homegrown terrorism has started to be seen as a greater threat, as stated by former CIA Director Michael Hayden.[124] This dilemma, some social theorists would conclude, may very well play into the initial plans of the acting terrorist(s); namely, to delegitimize the state and cause a systematic shift towards anarchy via the accumulation of negative sentiments towards the state system.[125]

Connection with tourism

The connection between terrorism and tourism has been widely studied since the Luxor massacre in Egypt.[177][178] In the 1970s, the targets of terrorists were politicians and chiefs of police while now, international tourists and visitors are selected as the main targets of attacks. The attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001, were the symbolic center, which marked a new epoch in the use of civil transport against the main power of the planet.[179] From this event onwards, the spaces of leisure that characterized the pride of West were conceived as dangerous and frightful.[180][181]

Terrorist attacks are often targeted to maximize fear and publicity, most frequently using explosives.[198]

Terrorist groups usually methodically plan attacks in advance, and may train participants, plant undercover agents, and raise money from supporters or through organized crime. Communications occur through modern telecommunications, or through old-fashioned methods such as couriers. There is concern about terrorist attacks employing weapons of mass destruction. Some academics have argued that while it is often assumed terrorism is intended to spread fear, this is not necessarily true, with fear instead being a by-product of the terrorist's actions, while their intentions may be to avenge fallen comrades or destroy their perceived enemies.[199]

Terrorism is a form of asymmetric warfare and is more common when direct conventional warfare will not be effective because opposing forces vary greatly in power.[200] Yuval Harari argues that the peacefulness of modern states makes them paradoxically more vulnerable to terrorism than pre-modern states. Harari argues that because modern states have committed themselves to reducing political violence to almost zero, terrorists can, by creating political violence, threaten the very foundations of the legitimacy of the modern state. This is in contrast to pre-modern states, where violence was a routine and recognised aspect of politics at all levels, making political violence unremarkable. Terrorism thus shocks the population of a modern state far more than a pre-modern one and consequently the state is forced to overreact in an excessive, costly and spectacular manner, which is often what the terrorists desire.[201]

The type of people terrorists will target is dependent upon the ideology of the terrorists. A terrorist's ideology will create a class of "legitimate targets" who are deemed as its enemies and who are permitted to be targeted. This ideology will also allow the terrorists to place the blame on the victim, who is viewed as being responsible for the violence in the first place.[202][203]

The context in which terrorist tactics are used is often a large-scale, unresolved political conflict. The type of conflict varies widely; historical examples include:

The following terrorism databases are or were made publicly available for research purposes, and track specific acts of terrorism:

The following public report and index provides a summary of key global trends and patterns in terrorism around the world:

The following publicly available resources index electronic and bibliographic resources on the subject of terrorism:

The following terrorism databases are maintained in secrecy by the United States Government for intelligence and counterterrorism purposes:

Jones and Libicki (2008) includes a table of 268 terrorist groups active between 1968 and 2006 with their status as of 2006: still active, splintered, converted to nonviolence, removed by law enforcement or military, or won. (These data are not in a convenient machine-readable format but are available.)