Divisionism

Divisionism, also called chromoluminarism, is the characteristic style in Neo-Impressionist painting defined by the separation of colors into individual dots or patches that interact optically.[1][2]

See also: PointillismBy requiring the viewer to combine the colors optically instead of physically mixing pigments, Divisionists believed that they were achieving the maximum luminosity scientifically possible. Georges Seurat founded the style around 1884 as chromoluminarism, drawing from his understanding of the scientific theories of Michel Eugène Chevreul, Ogden Rood and Charles Blanc, among others. Divisionism developed along with another style, Pointillism, which is defined specifically by the use of dots of paint and does not necessarily focus on the separation of colors.[1][3]

A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte

1884–1886

207.6 cm × 308 cm (81.7 in × 121.3 in)

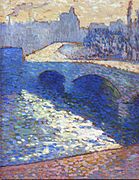

1890

73.5 cm × 92.5 cm (28.9 in × 36.4 in)

1888

44 cm × 37.5 cm (17.3 in × 14.8 in)

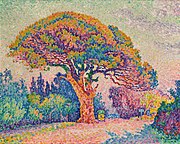

1906

73 cm × 54 cm (28.7 in × 21.2 in)

Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, Netherlands

1906

72.4 cm × 48.5 cm (28.5 in × 19.1 in)

Divisionism in France and Northern Europe[edit]

In addition to Signac, other French artists, largely through associations in the Société des Artistes Indépendants, adopted some Divisionist techniques, including Camille and Lucien Pissarro, Albert Dubois-Pillet, Charles Angrand, Maximilien Luce, Henri-Edmond Cross and Hippolyte Petitjean.[13] Additionally, through Paul Signac's advocacy of Divisionism, an influence can be seen in some of the works of Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay and Pablo Picasso.[13][14]

In 1907 Metzinger and Delaunay were singled out by the critic Louis Vauxcelles as Divisionists who used large, mosaic-like 'cubes' to construct small but highly symbolic compositions.[15] Both artists had developed a new sub-style that had great significance shortly thereafter within the context of their Cubist works. Piet Mondrian, Jan Sluijters and Leo Gestel, in the Netherlands, developed a similar mosaic-like Divisionist technique circa 1909. The Futurists later (1909–1916) would adapt the style, in part influenced by Gino Severini's Parisian experience (from 1907), into their dynamic paintings and sculpture.[16]

Divisionism in Italy[edit]

The influence of Seurat and Signac on some Italian painters became evident in the First Triennale in 1891 in Milan. Spearheaded by Grubicy de Dragon, and codified later by Gaetano Previati in his Principi scientifici del divisionismo of 1906, a number of painters mainly in Northern Italy experimented to various degrees with these techniques.

Pellizza da Volpedo applied the technique to social (and political) subjects; in this he was joined by Morbelli and Longoni. Among Pellizza's Divisionist works were Speranze deluse (1894) and Il sole nascente (1904).[17] It was, however, in the subject of landscapes that divisionism found strong advocates, including Giovanni Segantini, Gaetano Previati, Angelo Morbelli and Matteo Olivero. Further adherents in painting genre subjects were Plinio Nomellini, Rubaldo Merello, Giuseppe Cominetti, Camillo Innocenti, Enrico Lionne and Arturo Noci. Divisionism was also in important influence in the work of Futurists Gino Severini (Souvenirs de Voyage, 1911); Giacomo Balla (Arc Lamp, 1909);[18] Carlo Carrà (Leaving the scene, 1910); and Umberto Boccioni (The City Rises, 1910).[1][19][20]