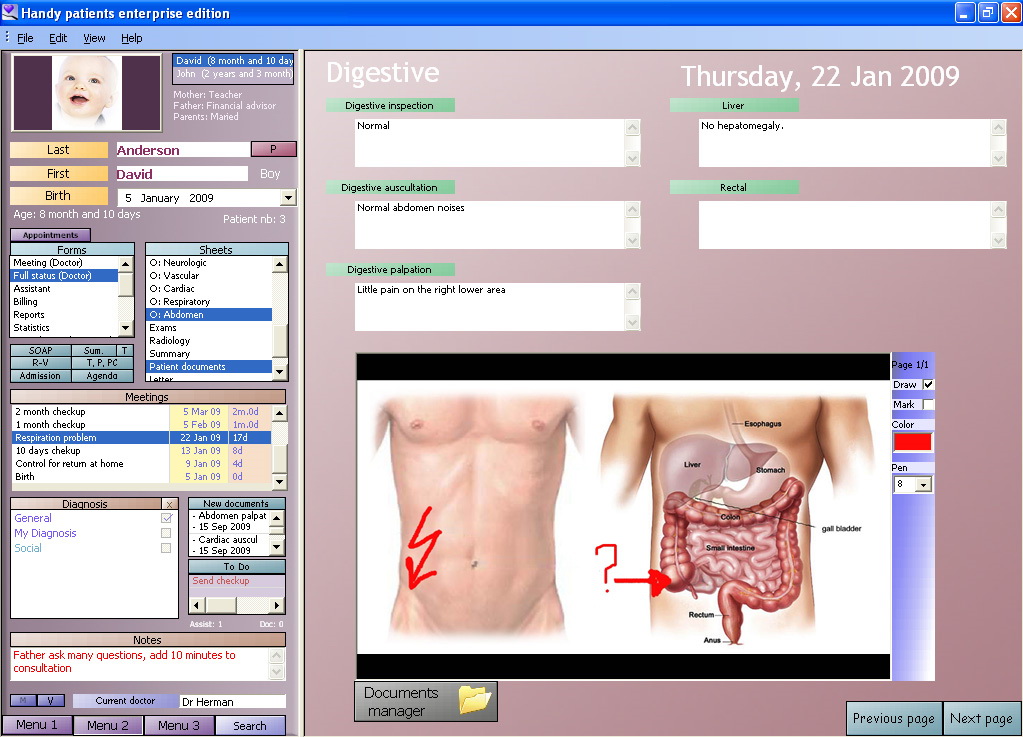

Electronic health record

An electronic health record (EHR) is the systematized collection of patient and population electronically stored health information in a digital format.[1] These records can be shared across different health care settings. Records are shared through network-connected, enterprise-wide information systems or other information networks and exchanges. EHRs may include a range of data, including demographics, medical history, medication and allergies, immunization status, laboratory test results, radiology images, vital signs, personal statistics like age and weight, and billing information.[2]

This article is about all types of electronic health records. For prescriptions, see Electronic prescribing.

For several decades, electronic health records (EHRs) have been touted as key to increasing of quality care.[3] Electronic health records are used for other reasons than charting for patients;[4] today, providers are using data from patient records to improve quality outcomes through their care management programs. EHR combines all patients demographics into a large pool, and uses this information to assist with the creation of "new treatments or innovation in healthcare delivery" which overall improves the goals in healthcare.[4] Combining multiple types of clinical data from the system's health records has helped clinicians identify and stratify chronically ill patients. EHR can improve quality care by using the data and analytics to prevent hospitalizations among high-risk patients.

EHR systems are designed to store data accurately and to capture the state of a patient across time. It eliminates the need to track down a patient's previous paper medical records and assists in ensuring data is up-to-date,[5] accurate and legible. It also allows open communication between the patient and the provider, while providing "privacy and security."[5] It can reduce risk of data replication as there is only one modifiable file, which means the file is more likely up to date and decreases risk of lost paperwork and is cost efficient.[5] Due to the digital information being searchable and in a single file, EMRs (electronic medical records) are more effective when extracting medical data for the examination of possible trends and long term changes in a patient. Population-based studies of medical records may also be facilitated by the widespread adoption of EHRs and EMRs.

Terminology[edit]

The terms EHR, electronic patient record (EPR) and EMR have often been used interchangeably, but differences between the models are now being defined. The electronic health record (EHR) is a more longitudinal collection of the electronic health information of individual patients or populations. The EMR, in contrast, is the patient record created by providers for specific encounters in hospitals and ambulatory environments and can serve as a data source for an EHR.[6][7]

In contrast, a personal health record (PHR) is an electronic application for recording personal medical data that the individual patient controls and may make available to health providers.[8]

Emergency medical services[edit]

Ambulance services in Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom have introduced the use of EMR systems.[58][59] EMS Encounters in the United States are recorded using various platforms and vendors in compliance with the NEMSIS (National EMS Information System) standard.[60] The benefits of electronic records in ambulances include: patient data sharing, injury/illness prevention, better training for paramedics, review of clinical standards, better research options for pre-hospital care and design of future treatment options, data based outcome improvement, and clinical decision support.[61]

Health Information Exchange[62]

Using an EMR to read and write a patient's record is not only possible through a workstation but, depending on the type of system and health care settings, may also be possible through mobile devices that are handwriting capable,[63] tablets and smartphones. Electronic Medical Records may include access to Personal Health Records (PHR) which makes individual notes from an EMR readily visible and accessible for consumers.

Some EMR systems automatically monitor clinical events, by analyzing patient data from an electronic health record to predict, detect and potentially prevent adverse events. This can include discharge/transfer orders, pharmacy orders, radiology results, laboratory results and any other data from ancillary services or provider notes.[64] This type of event monitoring has been implemented using the Louisiana Public health information exchange linking statewide public health with electronic medical records. This system alerted medical providers when a patient with HIV/AIDS had not received care in over twelve months. This system greatly reduced the number of missed critical opportunities.[65]

Philosophical views[edit]

Within a meta-narrative systematic review of research in the field, various different philosophical approaches to the EHR exist.[9] The health information systems literature has seen the EHR as a container holding information about the patient, and a tool for aggregating clinical data for secondary uses (billing, audit, etc.). However, other research traditions see the EHR as a contextualised artifact within a socio-technical system. For example, actor-network theory would see the EHR as an actant in a network,[66] and research in computer supported cooperative work (CSCW) sees the EHR as a tool supporting particular work.

Several possible advantages to EHRs over paper records have been proposed, but there is debate about the degree to which these are achieved in practice.[67]

Implementation[edit]

Quality[edit]

Several studies call into question whether EHRs improve the quality of care.[9][68][69][70][71] One 2011 study in diabetes care, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, found evidence that practices with EHR provided better quality care.[72]

EMRs may eventually help improve care coordination. An article in a trade journal suggests that since anyone using an EMR can view the patient's full chart, it cuts down on guessing histories, seeing multiple specialists, smooths transitions between care settings, and may allow better care in emergency situations.[73] EHRs may also improve prevention by providing doctors and patients better access to test results, identifying missing patient information, and offering evidence-based recommendations for preventive services.[74]

Costs[edit]

The steep price and provider uncertainty regarding the value they will derive from adoption in the form of return on investment has a significant influence on EHR adoption.[75] In a project initiated by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information, surveyors found that hospital administrators and physicians who had adopted EHR noted that any gains in efficiency were offset by reduced productivity as the technology was implemented, as well as the need to increase information technology staff to maintain the system.[75]

The U.S. Congressional Budget Office concluded that the cost savings may occur only in large integrated institutions like Kaiser Permanente, and not in small physician offices. They challenged the Rand Corporation's estimates of savings. "Office-based physicians in particular may see no benefit if they purchase such a product—and may even suffer financial harm. Even though the use of health IT could generate cost savings for the health system at large that might offset the EHR's cost, many physicians might not be able to reduce their office expenses or increase their revenue sufficiently to pay for it. For example, the use of health IT could reduce the number of duplicated diagnostic tests. However, that improvement in efficiency would be unlikely to increase the income of many physicians."[76] One CEO of an EHR company has argued if a physician performs tests in the office, it might reduce his or her income.[77]

Doubts have been raised about cost saving from EHRs by researchers at Harvard University, the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, Stanford University, and others.[71][78][79]

In 2022 the chief executive of Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust, one of the biggest NHS organisations, said that the £450 million cost over 15 years to install the Epic Systems electronic patient record across its six hospitals, which will reduce more than 100 different IT systems down to just a handful, was "chicken feed" when compared to the NHS's overall budget.[80]

Time[edit]

The implementation of EMR can potentially decrease identification time of patients upon hospital admission. A research from the Annals of Internal Medicine showed that since the adoption of EMR a relative decrease in time by 65% has been recorded (from 130 to 46 hours).[81]

Software quality and usability deficiencies[edit]

The Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society, a very large U.S. healthcare IT industry trade group, observed in 2009 that EHR adoption rates "have been slower than expected in the United States, especially in comparison to other industry sectors and other developed countries. A key reason, aside from initial costs and lost productivity during EMR implementation, is lack of efficiency and usability of EMRs currently available."[82][83] The U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology of the Department of Commerce studied usability in 2011 and lists a number of specific issues that have been reported by health care workers.[84] The U.S. military's EHR, AHLTA, was reported to have significant usability issues.[85] Furthermore, studies such as the one conducted in BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, also showed that although the implementation of electronic medical records systems has been a great assistance to general practitioners there is still much room for revision in the overall framework and the amount of training provided.[86] It was observed that the efforts to improve EHR usability should be placed in the context of physician-patient communication.[87]

However, physicians are embracing mobile technologies such as smartphones and tablets at a rapid pace. According to a 2012 survey by Physicians Practice, 62.6 percent of respondents (1,369 physicians, practice managers, and other healthcare providers) say they use mobile devices in the performance of their job. Mobile devices are increasingly able to sync up with electronic health record systems thus allowing physicians to access patient records from remote locations. Most devices are extensions of desk-top EHR systems, using a variety of software to communicate and access files remotely. The advantages of instant access to patient records at any time and any place are clear, but bring a host of security concerns. As mobile systems become more prevalent, practices will need comprehensive policies that govern security measures and patient privacy regulations.[88]

Other advanced computational techniques have allowed EHRs to be evaluated at a much quicker rate. Natural language processing is increasingly used to search EMRs, especially through searching and analyzing notes and text that would otherwise be inaccessible for study when seeking to improve care.[89] One study found that several machine learning methods could be used to predict the rate of a patient's mortality with moderate success, with the most successful approach including using a combination of a convolutional neural network and a heterogenous graph model.[90]

Hardware and workflow considerations[edit]

When a health facility has documented their workflow and chosen their software solution they must then consider the hardware and supporting device infrastructure for the end users. Staff and patients will need to engage with various devices throughout a patient's stay and charting workflow. Computers, laptops, all-in-one computers, tablets, mouse, keyboards and monitors are all hardware devices that may be utilized. Other considerations will include supporting work surfaces and equipment, wall desks or articulating arms for end users to work on. Another important factor is how all these devices will be physically secured and how they will be charged that staff can always utilize the devices for EHR charting when needed.

The success of eHealth interventions is largely dependent on the ability of the adopter to fully understand workflow and anticipate potential clinical processes prior to implementations. Failure to do so can create costly and time-consuming interruptions to service delivery.[91]

Unintended consequences[edit]

Per empirical research in social informatics, information and communications technology (ICT) use can lead to both intended and unintended consequences.[92][93][94]

A 2008 Sentinel Event Alert from the U.S. Joint Commission, the organization that accredits American hospitals to provide healthcare services, states, 'As health information technology (HIT) and 'converging technologies'—the interrelationship between medical devices and HIT—are increasingly adopted by health care organizations, users must be mindful of the safety risks and preventable adverse events that these implementations can create or perpetuate. Technology-related adverse events can be associated with all components of a comprehensive technology system and may involve errors of either commission or omission. These unintended adverse events typically stem from human-machine interfaces or organization/system design."[95] The Joint Commission cites as an example the United States Pharmacopeia MEDMARX database[96] where of 176,409 medication error records for 2006, approximately 25 percent (43,372) involved some aspect of computer technology as at least one cause of the error.

The British National Health Service (NHS) reports specific examples of potential and actual EHR-caused unintended consequences in its 2009 document on the management of clinical risk relating to the deployment and use of health software.[97]

In a February 2010, an American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) memorandum noted that EHR unintended consequences include EHR-related medical errors from (1) errors of commission (EOC), (2) errors of omission or transmission (EOT), (3) errors in data analysis (EDA), and (4) incompatibility between multi-vendor software applications or systems (ISMA), examples were cited. The FDA also noted that the "absence of mandatory reporting enforcement of H-IT safety issues limits the numbers of medical device reports (MDRs) and impedes a more comprehensive understanding of the actual problems and implications."[98][99]

A 2010 Board Position Paper by the American Medical Informatics Association (AMIA) contains recommendations on EHR-related patient safety, transparency, ethics education for purchasers and users, adoption of best practices, and re-examination of regulation of electronic health applications.[100] Beyond concrete issues such as conflicts of interest and privacy concerns, questions have been raised about the ways in which the physician-patient relationship would be affected by an electronic intermediary.[101][102]

During the implementation phase, cognitive workload for healthcare professionals may be significantly increased as they become familiar with a new system.[103]

EHRs are almost invariably detrimental to physician productivity, whether the data is entered during the encounter or sometime thereafter.[104] It is possible for an EHR to increase physician productivity [105] by providing a fast and intuitive interface for viewing and understanding patient clinical data and minimizing the number of clinically irrelevant questions, but that is almost never the case. The other way to mitigate the detriment to physician productivity is to hire scribes to work alongside medical practitioners, which is almost never financially viable.

As a result, many have conducted studies like the one discussed in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, "The Extent And Importance of Unintended Consequences Related To Computerized Provider Order Entry," which seeks to understand the degree and significance of unplanned adverse consequences related to computerized physician order entry and understand how to interpret adverse events and understand the importance of its management for the overall success of computer physician order entry.[106]

Governance, privacy and legal issues[edit]

Privacy concerns[edit]

In the United States, Great Britain, and Germany, the concept of a national centralized server model of healthcare data has been poorly received.[107] Issues of privacy and security in such a model have been of concern.[108][109]

In the European Union (EU), a new directly binding instrument, a regulation of the European Parliament and of the council, was passed in 2016 to go into effect in 2018 to protect the processing of personal data, including that for purposes of health care, the General Data Protection Regulation.

Threats to health care information can be categorized under three headings:

Contribution under UN administration and accredited organizations[edit]

The United Nations World Health Organization (WHO) administration intentionally does not contribute to an internationally standardized view of medical records nor to personal health records. However, WHO contributes to minimum requirements definition for developing countries.[125]

The United Nations accredited standardization body International Organization for Standardization (ISO) however has settled thorough word for standards in the scope of the HL7 platform for health care informatics. Respective standards are available with ISO/HL7 10781:2009 Electronic Health Record-System Functional Model, Release 1.1[126] and subsequent set of detailing standards.[127]

Initiatives[edit]

Russia[edit]

In 2011, Moscow's government launched a major project known as UMIAS as part of its electronic healthcare initiative. UMIAS - the Unified Medical Information and Analytical System - connects more than 660 clinics and over 23,600 medical practitioners in Moscow. UMIAS covers 9.5 million patients, contains more than 359 million patient records and supports more than 500,000 different transactions daily. Approximately 700,000 Muscovites use remote links to make appointments every week.[144][145]

European Union[edit]

The European Commission wants to boost the digital economy by enabling all Europeans to have access to online medical records anywhere in Europe by 2020. With the newly enacted Directive 2011/24/EU on patients' rights in cross-border healthcare due for implementation by 2013, it is inevitable that a centralised European health record system will become a reality even before 2020. However, the concept of a centralised supranational central server raises concern about storing electronic medical records in a central location. The privacy threat posed by a supranational network is a key concern. Cross-border and Interoperable electronic health record systems make confidential data more easily and rapidly accessible to a wider audience and increase the risk that personal data concerning health could be accidentally exposed or easily distributed to unauthorised parties by enabling greater access to a compilation of the personal data concerning health, from different sources, and throughout a lifetime.[146]

Turing test[edit]

A letter published in Communications of the ACM[153] describes the concept of generating synthetic patient population and proposes a variation of Turing test to assess the difference between synthetic and real patients. The letter states: "In the EHR context, though a human physician can readily distinguish between synthetically generated and real live human patients, could a machine be given the intelligence to make such a determination on its own?" and further the letter states: "Before synthetic patient identities become a public health problem, the legitimate EHR market might benefit from applying Turing Test-like techniques to ensure greater data reliability and diagnostic value. Any new techniques must thus consider patients' heterogeneity and are likely to have greater complexity than the Allen eighth-grade-science-test is able to grade."[154]